The disease infects humans through close contact with infected animals, including chimpanzees, fruit Bats and forest antelope. It then spreads between humans by direct contact with infected blood, bodily fluids or organs, or indirectly through contact with contaminated environments. Even funerals of Ebola victims can be a risk, if mourners have direct contact with the body of the deceased. The incubation period can last from two days to three weeks, and diagnosis is difficult. The human disease has so far been mostly limited to Africa, although one strain has cropped up in The Philippines.

Where does it strike?

Ebola outbreaks occur primarily in remote villages in Central and West Africa, near tropical rainforests, says the WHO. It was first discovered in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1976 since when it has affected countries further east, including Uganda and Sudan. This outbreak is unusual because it started in Guinea, which has never before been affected, and is spreading to urban areas.

Can cultural practices spread Ebola?

Ebola is spread through close physical contact with infected people.

This is a problem for many in the West African countries currently affected by the outbreak, as practices around religion and death involve close physical contact.

Hugging is a normal part of religious worship in Liberia and Sierra Leone, and across the region the ritual preparation of bodies for burial involves washing, touching and kissing. Those with the highest status in society are often charged with washing and preparing the body. For a woman this can include braiding the hair, and for a man shaving the head.

If a person has died from Ebola, their body will have a very high viral load. Bleeding is a usual symptom of the disease prior to death.

Those who handle the body and come into contact with the blood or other body fluids are at greatest risk of catching the disease. Medecin Sans Frontiere, MSF, has been trying to make people aware of how their treatment of dead relatives might pose a risk to themselves. It is a very difficult message to get across.

All previous outbreaks were much smaller and occurred in places where Ebola was already known – in Uganda and the DR Congo for example. In those places the education message about avoiding contact has had years to enter the collective consciousness.

In West Africa, there simply has not been the time for the necessary cultural shift.

What precautions should you take?

Avoid contact with Ebola patients and their bodily fluids, the WHO advises. Do not touch anything – such as shared towels – which could have become contaminated in a public place. Carers should wear gloves and protective equipment, such as masks, and wash their hands regularly. The WHO also warns against consuming raw bushmeat and any contact with infected bats or monkeys and apes. Fruit bats in particular are considered a delicacy in the area of Guinea where the outbreak started.

In March, Liberia’s health minister advised people to stop having sex, in addition to existing advice not to shake hands or kiss. The WHO says men can still transmit the virus through their semen for up to seven weeks after recovering from Ebola.

The WHO ruled in August that untested drugs can be used to treat patients in light of the scale of the current outbreak. Patients with Ebola frequently become dehydrated. They should drink solutions containing electrolytes or receive intravenous fluids.

MSF says this outbreak comes from the deadliest and most aggressive strain of the virus.

The current outbreak is killing between 50% and 60% of people infected.

It is not known which factors allow some people to recover while most succumb.

Right precautions

Healthcare workers are at risk if they treat patients without taking the right precautions to avoid infection. People are infectious as long as their blood and secretions contain the virus – in some cases, up to seven weeks after they recover.

Ebola outbreak moving faster than medics can handle

The Ebola outbreak that has claimed more than 1,000 lives in west Africa is moving faster than aid organisations can handle, the medical charity MSF said Friday.

The warning came a day after the World Health Organization said the scale of the epidemic had been vastly underestimated and that “extraordinary measures” were needed to contain the killer disease.

The UN health agency said the death toll from the worst outbreak of the disease in four decades had now climbed to 1,069 in the four afflicted countries, Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone.

“It is deteriorating faster, and moving faster, than we can respond to,” MSF (Doctors Without Borders) chief Joanne Liu told reporters in Geneva, saying it could take six months to get the upper hand.

“It is like wartime,” she said a day after returning from the region where she met political leaders and visited clinics.

WHO said Thursday it was coordinating “a massive scaling up of the international response” to the epidemic.

“Staff at the outbreak sites see evidence that the numbers of reported cases and deaths vastly underestimate the magnitude of the outbreak,” it said.

The latest epidemic erupted in the forested zone straddling the borders of Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, and later spread to Nigeria.

WHO declared a global health emergency last week — far too late, according to MSF, which months ago warned that the outbreak was out of control.

Liu said while Guinea was the initial epicenter of the disease, the pace there has slowed, with concerns now focused on the other countries.

“If we don’t stabilize Liberia, we’ll never stabilize the region,” Liu said.

Concerns have also centered on the Nigerian cases, which are in Lagos, sub-Saharan Africa’s largest city.

“Right now we have no past experience with in urban setting,” said Liu.

- Athletes barred -

As countries around the world stepped up measures to contain the disease, the International Olympics Committee said athletes from Ebola-hit countries had been barred from competing in pool events and combat sports at the Youth Olympics opening in China on Saturday.

The decision, which affects three unidentified athletes, was made “with regard to ensuring the safety of all those participating” in the Games in the city of Nanjing, the IOC and Chinese organizers said.

No cure or vaccine is currently available for Ebola, which the WHO has declared a global public health emergency.

It has also authorized the use of largely untested treatments in efforts to combat the disease.

Hard-hit nations are awaiting consignments of up to 1,000 doses of the barely tested drug ZMapp from the United States, which has raised hopes of saving hundreds.

Canada says between 800 and 1,000 doses of a vaccine called VSV-EBOV, which has shown promise in animal research but never been tested on humans, would also be distributed through the WHO.

MSF’s Liu warned against focusing on drugs.

“In the short term, they’re not going to help that much, because we don’t have many drugs available.

We need to a get a reality check on how this could impact the curve of the epidemic,” she said.

The last days of an Ebola victim can be grim, characterized by agonizing muscular pain, vomiting, diarrhea and catastrophic hemorrhaging described as “bleeding out” as vital organs break down.

The cost of tackling the virus is also threatening to exact a severe economic toll on the already impoverished west African nations hit by the epidemic.

In Nigeria, in particular, a more serious outbreak could severely disrupt its oil and gas industry if international companies are forced to evacuate staff and shut local operations, rating agency Moody’s warned.

- ‘Hostility to health workers’ -

Sierra Leone’s chief medical officer Brima Kargbo this week spoke of the risks facing health workers fighting the epidemic, which has killed 32 nurses since May as well as an eminent doctor, of a total of more than 330 victims.

“We still have to break the chain of transmission to separate the infected from the uninfected,” Kargbo said.

In Liberia, which has recorded more than 300 deaths, work has begun on expanding a treatment center in Monrovia — one of only two such clinics in the country of 4.2 million.

Across the region, draconian restrictions have been imposed and a number of airlines have cancelled flights in and out of west Africa.

Guinea, where at least 377 people have died, became the latest country to declare a health emergency, ordering strict controls at border points and a ban on moving bodies from one town to another.

Although the WHO confirmed that other African countries, including Kenya, were labelled “high risk” due to their popular transport hubs, it also emphasized that air travel, even from Ebola-affected countries, is low risk because the virus is not airborne.

World Health Organization Approves Use of Experimental Ebola Treatment

The drugs have not yet been through FDA testing, but WHO says they can be used for “compassionate Use” to help in the African outbreak. However, manufacturers may not have many supplies available.

Los Angeles Times: WHO OKs Use Of Experimental Drugs for Ebola Patients In West Africa A World Health Organization panel advised Tuesday that it was ethical to use experimental, non-Approved drugs to combat the Ebola virus in West Africa, and that five such treatments were being Considered for “compassionate use”

Ebola Medicines

The endorsement from the U.N.’s health care agency came after two American health care workers were treated with an experimental Ebola drug. Officials warned, however, that the improvement they showed may not have been directly related to the drugs.

WHO says 1,013 people have died since March in the Outbreak, the vast majority of them in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea. Officials estimate that Ebola kills About half of those afflicted with the disease (Bacon and Weintraub, 8/12).PBS News Hour: WHO

Approves Use Of Untested Drugs To Fight Ebola, But Supply May Be Running Out

An ethics panel of the World Health Organization unanimously approved using untested drugs to treat Ebola in West Africa, where more than 1,000 people have died from the outbreak so far. A shipment of The U.S.-made drug ZMapp is expected to arrive in Liberia this week, but the drug maker may have Otherwise exhausted its supply (Woodruff, 8/12).

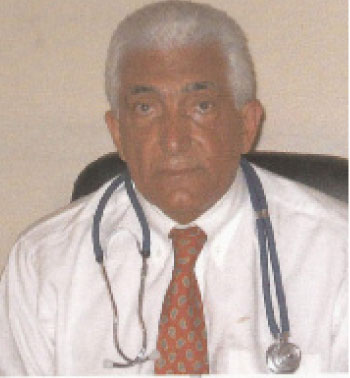

For further information visit the WHO web site, or visit the WHO office in the Gambia, MRC, EFSTH, or E- Mail azadehhassan@yahoo.co.uk, text Dr Azadeh on 00220 7774469/3774469 during the working hours from 3-6 pm.

Author: DR H. Azadeh Senior Lecturer at the University of the Gambia, Senior Physician and Senior Consultant in Obstetrics & Gynaecoogy.