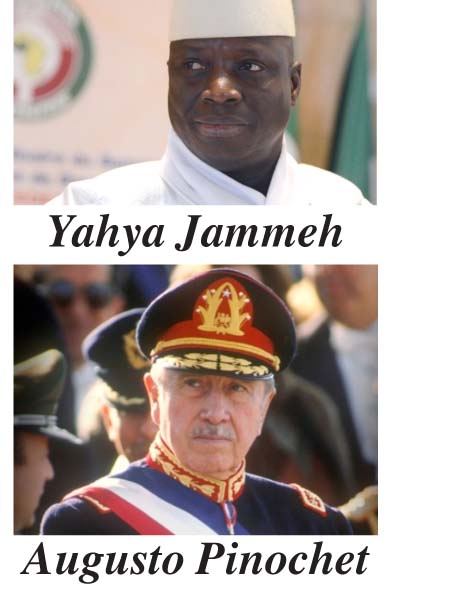

To

draw plausible conclusions as to whether justice would be served for alleged

human rights abuses committed by state officers in the Second Republic, it is necessary

for one to revisit the case of Senator Augusto Pinochet as it may allow us to

understand the importance international law attaches to the protection of

peremptory norms. This will also help us to examine the extent to which

international human rights law has evolved to disallow the use of state

immunity doctrine to shield perpetrators of deplorable crimes from prosecution.

Augusto

Pinochet was significant and a symbolic figure in many ways. In diplomatic

sense, it was unprecedented for a state to arrest another sovereign state’s

former head at a request of another foreign power. It constituted the end of

states’ cautious approach to interfere in internal affairs of another state. No

wonder it had generated ceaseless glare of media attention. The Spanish

authorities were not prepared to settle for anything less than a speedy

extradition of the General to face criminal trial for alleged human rights

abuses commissioned under his watch.

.’It was contended that Chile had a vested right to immunity to the General and

that no other State had the right to exercise jurisdiction over his crimes.

Moreover, such protection is in accord with the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic

Protection which provides former heads of state with immunity ratione materiae.

It follows that Chile as an independent and sovereign state has the necessary

legal capacity to confer such right on its former head of state. The House of

Lords rejected this argument by displacing the state immunity doctrine for

justice to take its course.

Your

lordships took the view that state immunity should not be invoked as facade to

cover up international crimes. Certainly, it defies common sense for an

abstract state to commit serious crime against the very citizens it has a

sovereign duty to protect. In the words of Lord Slyn ‘it is artificial to say

that an evil act can be treated as a function of a head of state’. In my view,

perpetrators of such crimes represent the controlled mind of the state.

Therefore, they should face the full force of the law if found guilty of their

crimes. There can be no doubt if international law fails to hold such men

responsible for culpable crimes; impunity seems the likely consequence.

It was a known fact that the Senator had a

well-established close nexus with the UK’s political establishment. But as a

state party to the Torture Convention, the UK has an obligation to make sure

that crimes within the scope of the Convention are punishable by national laws.

It is also the case that the UK has extradition treaty with Spain which

provides that the perpetrators such of offence be extradited within a

reasonable time. Undoubtedly, the case affirmed that no head of state has

blanket immunity against crimes that have a character of Jus cogen.

Importantly, it places the community’s security over individual’s security that

is crafted in state immunity doctrine.

Turning

to human right abuses allegedly committed by state officers in the Second

Republic. Firstly, The Gambia must bring criminal charges against those

perpetrators for their role in such distasteful crimes to create the right

momentum. Indeed, the perpetrators must be presumed innocent until proven

guilty by a competent court. That is an important principle of fair trial. It

will be against all principles of justice for defendants to be tried by the

public opinion or the media.

Subsequently,

the government may choose to seek extradition of the perpetrators provided that

there is enforceable extradition treaty between The Gambia and their country of

residence. Absent of extradition treaty is likely to stall any proceedings. For

instance, In 2004 Equatorial Guinea did not secure the extradition of foreign

mercenaries who were allegedly involved in a plot to oust its government

because there was no extradition treaty. A deliberate omission designed to

insulate a culture of impunity, but sounded death knell for the efforts to

bring the perpetrators to justice. It is interesting to note that, there is no

extradition treaty agreement between Equatorial Guinea and The Gambia. Perhaps,

this explains why Equatorial Guinea is seen as a preferred destination for

anyone who might be implicated in the alleged human rights abuses that occurred

in the Second Republic.

What

is more striking is that The Gambia has not yet ratified the Torture

Convention. This raises the question whether state officers who were complicit

in commission of torture could be brought to justice under the Convention. It

is undisputable fact that the both Republics had abysmally failed to give

effective to one of the most seminal human rights instrument that accords

comprehensive protection to the citizens’ human rights. The Torture Convention

has been ratified by majority of states; even Equatorial Guinea has acceded to

the Convention in 2002.

The

inaction of successive Gambia governments suggests, there could be inherent

difficult legal challenges ahead to bring any successful prosecution.

Nevertheless, if justice is to be delivered the new government must be ready to

take bold actions to overcome such challenges.

The 1997 constitution of the Gambia prohibits

torture under Section 21. However, it could be argued that it is not precise to

make attempts and complicity as criminal offences. If there are no national

laws pertaining to such offences, the secret services agents and law

enforcement officers may be absolved from certain criminal liabilities under

the Convention. The other important

point is that the Convention has the necessary ingredients that can compel

state party to take training and educational measures, in order to equip

relevant state officers with the knowledge and skills on how to relate with the

civil populace. That way , they can perform their duty with diligence in

respect of citizens’ human rights. Therefore, It is incomprehensible, a government

that supposed to have the interest of its people at heart failed to confer much

needed protection on citizens. The omission can only be seen as a travesty to

the intelligence of Gambians, an absolute failure to govern in good faith. It

suggests here that governments were more interested in asserting their grip on

power rather than guaranteeing the security of Gambians.

Notwithstanding,

the torture Convention categorically prohibits torture and no state can

derogate from it because it has become peremptory norms. That been the case

there is a glimpse of hope for justice

if Equatorial Guinea and other state parties adhere to their obligation under

the Convention, by taking reasonable steps and facilitate proper dispensation

of justice.

They

could either execute arrest warrant put forward by a requesting state, or they

may well assert jurisdiction over the crimes under the ambit of the Convention.

This is illustrated in the recent Swiss case where a former government officer

was reportedly arrested for crime against humanity. Such decisive action is

likely to be lauded by many around the world. Importantly, it would provide an

opportunity for state such as Guinea to unmask its perceived ‘rough state

image’ and uphold international justice.

While

punitive justice seems desirable because of its deterrence effect on the

perpetrators, the truth reconciliation process may also deliver justice as well

as unify the nation. The story telling of the historical facts can bring

closure to the sufferings and pains of those affected by the atrocities as they

learn the unambiguous truth about what had happened. Despite this, there is a danger that the

process may be stymied, if tension is allowed to rife between those who want

retributive justice as opposed to those who favour reconciliation. Therefore,

there is a need for an active political leadership to engage all stakeholders

in good faith for the construction of the Commission. Whatever the

circumstance, it helps greatly if the perpetrators are remorseful about their crimes.

If the new government managed to reverse the

decision of leaving the ICC, it can allow court to have jurisdiction over some

cases. However, crimes against humanity must meet the requirement of widespread

and systematic to fall under the ambit of the ICC. This requires adduction of

creditable evidences that are crucial to the success of any future trial. The

Chief Prosecutor could invoke the power of proprio motu power to investigate

any relevant crimes if they meet the necessary criteria. The power has been a subject of selectivity

because it has been mostly deployed to investigate African cases. Although the court has been seen by some

African leaders as an instrument of foreign powers that only target Africans,

the court is treaty based on state’s consent, depriving its authority from the

membership. Bensouda, the Chief Prosecutor, responding to such criticism said

this: ‘‘What offends me most when I hear

criticisms about the so-called African bias is how quick we are to focus on the

words and propaganda of a few powerful, influential individuals and to forget

about the millions of anonymous people that suffer from these crimes.’’ Surely

such propagandas are designed to undermine the authority of the Court. Let me

make it clear, the court has achieved justice for powerless Africans who were

brutalised by repressive regimes. I wonder if there is any strength in the

‘African bias argument when in fact these atrocities were committed on African

soils by callous Africans for political power.

The

case of Augusto Pinochet illustrates the point that international law has

fundamentally changed to make it difficult for the perpetrators of

international crimes to escape justice by hiding in safe haven. Individual

criminal act cannot be attributable to impersonate state for the purpose of

absolving one from criminal liability.

It is not only unrealistic but also offensive to all notions of justice

if state immunity is employed to cover up serious crimes committed by state

officers who have fallen from grace. Therefore, it is incumbent on the new

government to take all measures necessary and deliver justice for the victims.

This

can be achieved through truth and reconciliation mechanism or proper

application of the law. From now

onwards, the clock starts ticking while the jury is sent out to consider

verdict as to whether the government has the tenacity to avoid ‘‘Show Trials’!!

God

bless

Solomon

Demba