In

previous notes, we talked a little about the evolution of jazz from mainstream

to bebop and then back to mainstream jazz with a lot in between. It is also

very fascinating to explore the relationship between jazz and poetry, and how what

became known as “jazz poetry”, has its roots firmly embedded in the oral

tradition of African music. Jazz and poetry have long been associated together

because of the amount of freedom embedded in their practice, but each art form

(jazz/poetry) existed on its own, until the 1920’s when poets such as T. S.

Elliot and E. E. Cummings began using the conventions of rhythm and style in

their work. This development which was accompanied by the simultaneous

evolution of jazz and poetry, led to the merging of the two art forms into one,

namely –Jazz Poetry.

It

was conceived by African Americans in the 20’s, maintained in the 50’s by

counterculture (Beat) and adopted to modern times into rap and hip-hop. In the

50’s, it shifted focus from racial pride to spontaneity and freedom. Jazz

poetry and music have always been seen as effective mediums to make powerful

statements against the status quo at that time.

Jazz

is always about listening and sharing. There are a thousand ways to say

something, but the particular way one selects to express a thought, usually

reflects the person’s mental state. In African societies, music is learned

orally through the process of the master/student relationship. Master plays

something and tells the student to “make it sound like this”. The direct

experience of imitation (i.e. copying the master) introduces the student to the

music without intellectual intervention. It goes directly to the sound of the

music, as the intuition and the ears often know more than the intellect does.

The oral tradition is the process used by the master to efficiently pass

musical wisdom to succeeding generations of musicians. This wisdom is usually experiential and

difficult to record in written form. Miles Davis once said that “you only copy

from the best” and that “if it sounds good, you must have used the rules

correctly”. If you copy good sounds, you are learning the rules of music by

ear.

Jazz

proverbs are ubiquitous throughout the history of jazz. They make sense to you

at the time, but the information in them is usually hidden, and the other

dimensions are illuminated only after one has enough experience and has

acquired enough knowledge to relate to the proverb personally. Jazz proverbs

are very powerful and in the 60’s, poet Leroy Jones (Amiri Baraka) revived the

idea of jazz poetry as a source of black pride. Elements of jazz appear in his

work such as syncopation and repetition of phrases. This technique was

previously used by poet Langston Hughes and later by Gil Scott Heron in his

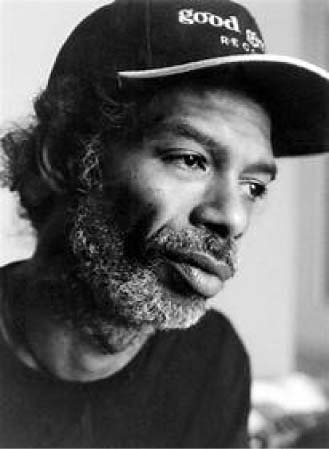

spoken word albums. Gil Scott Heron is the reason we started this piece looking

into the linkage between jazz and poetry. He died a few years ago in New York

after becoming ill upon returning from a European tour. He was an American

poet, musician and author, known primarily for his work as a spoken word

performer.

His

birth name is Gilbert (Gil) Heron. He was born in Chicago, Illinois on April

1st 1949, but grew in New York where he did his high school. His father was

Jamaican with the same name Gil Heron and his mother Bobby Scott Heron sang

with the New York Oratorio Society. Incidentally, his father was the first

black to play soccer for the Glasgow Celtic Football Club of Scotland. While in

New York, Gill attended the Dewitt Clinton High School and Fieldston Academy where

he excelled in English and developed very good writing skills. After high

school, he attended Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. The choice of Lincoln

was influenced by Gil’s longtime role model, Langston Hughes. Gill only spent

two years at Lincoln and took time off to write two novels, entitled “The

Vulture” and “The Nigger factory”. After the publication of “The Vulture” in

1970, he returned to school and obtained a Master’s Degree in creative writing

from John Hopkins University. However, his musical career got started during

his days at Lincoln, where he met Brian Jackson with whom he formed his first

band, called –Black and Blues. His collaborative efforts with Jackson featured

a musical fusion of jazz, blues and soul, as well as lyrical contents concerning

social and political issues of the time. Scott’s recording work is often

associated with black militant activism and he has recorded many songs on the

subject, gaining much critical acclaim for one of his most known compositions,

“The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”. His poetic style has influenced other

musicians in the generation of Rap and Hip Hop.

Although

he started playing music with Brian Jackson, his recording career began in 1970

with the release of the album “Small Talk at 125th and Lennox”. It was produced

by Bob Thiele for the “Flying Dutchman” label, and Scott was accompanied by

Eddie Knowles and Charlie Saunders on conga, with David Barnes on percussion

and vocals. In 1971, he released his second album entitled “Pieces of a Man” again

produced by Thiele, and this time joined by his friend Brian Jackson on piano,

Ron Carter on bass, Hubert Laws on flute and saxophone, Bernard Purdie on drums

and Burt Jones playing electric guitar. His third album “Free Will” was

produced the following year in 1972 with Horace Ott as arranger and conductor.

In

1974, Gil Scott again collaborated with Brian Jackson to release what would

become the two artist’s most artistic effort, “Winter in America”. It contained

Scott’s most cohesive material and brought out the best of Jackson’s creative

input. The following year, still working with Jackson, he released “The

Midnight Band: The First Minute of a Day”, and in 1976 they did a live album

called “It’s Your World” followed by a recording of spoken poetry “The Mind of

Gil Scott Heron” released in 1979. Scott would only release four albums in the

80’s, “Real Eyes” in 1980, “Reflections” in 1981, and “Moving Target” in 1982.

Tenor saxophonist Ron Holloway was added to Gil’s next album “Moving Target”

released that same year. Holloway stayed with Gil until in 1989 when he left to

join Dizzy Gillespie.

In

1985 after his contract with Arista was not renewed, Scott quit recording but

continued to tour. That same year, he helped compose and sang “Let Me See Your

I. D” on the Artist United against Apartheid album “Sun City”. In 1993, he

signed with TVT Records and released the album “Spirits” which included the

track “Message to the Messengers” which criticized the rap artist of the day

and urged them to speak for change rather than perpetuate the same social

situation. He wanted them to be more articulate and artistic. He disliked the

use of slang and colloquialism saying, it does not allow one to see the inside

of a person, and all you get is a lot of posturing.

Scott’s

later years would see him succumb to the evils of city life that he preached

against. In 2001 he was arrested for possession of cocaine and sentenced to one

to three years imprisonment in New York State. He would spend the next few

years in and out of prison because of drug use, and in 2008 he announced that

he was HIV positive. Scott however stayed active throughout this period and in

2010, he released his last album, which was also his first studio engagement in

16 years. The album entitled “I’m New Here “was started in 2007 but completed

in 2010, three years later. He continued to tour and perform live until the

afternoon of May 27th 2011 when he died at St Luke’s Hospital in New York City,

after becoming ill upon returning from a European trip. He was eulogized by

R&B singer Usher with the words “The Revolution Will Be Live”.