A couple of weeks ago former Gambian all round sports international Bai Malleh Wadda said on West Coast radio that “despite the many newspapers and radios and even a television station, even the most ardent football followers like himself does not know Gambian local players”.

He blames this on inadequate or lack of effective media coverage of Gambian football and challenges the media today to work much harder.

According to Malleh, and as agreed by most Gambians, only Radio Gambia was the radio covering football but it was so effective that everyone knew the name of a Gambian player in the league more so in the national team.

Well, Malleh Wadda’s observations connect very well with a portion of a book on Gambian football, written by Tijan Massaneh Cessay himself a former sports journalist.

Continuing our publication of snapshots from the book and taken a cue from Malleh’s admonition of the press today, we move this time to Chapter Six of Tijan’s book where the former most erudite student journalist from Father Gough’s Saints Augustine’s met his hero, the legendary Saul Njie of Radio Gambia, whose influence and personal tutelage made Tijan a delight to follow on radio during matches.

In this chapter, he describes their first encounter, when and how, before telling how subsequently, Saul Njie introduced him to football commentary and sports journalism alongside The Gambia’s most well known names in the trade.

That is the nostalgia Malleh Wadda so vividly described on West Coast the other night. Enjoy this masterpiece.

Sitting Next to and Learning from the Best: Radio Gambia’s Saul Njie

On March 14th, 1977, I was introduced to my hero, Saul Njie. Mr Gibbi Jallow, Proprietor of Banjul Mother Care introduced me. I recalled fully that day walking bare feet on the hot tar roads of Banjul into Box Bar Stadium.

On arrival at the western gate on Primet Street, Mr Jallow and I found a long line waiting to get in for what was a big derby game that day, Real vs. Wallidan.

We waited in line while people filed in, each paying three dalasis. Finally, we got to the paying spot. Mr Jallow paid his three dalasis and asked that I be let in free, because he was taking me to meet my idol Saul Njie. He went on to narrate how talented he found me to be and what I could become if I was encouraged.

The lady at the gate, a tall beautiful Banjul lady named Anta Kah, who was collecting the monies, was not buying it, and the Police Constable named Bojang but affectionately known as “Endurance” because of his commitment to duty, was not going to let me in anyway.

Mr Jallow was quite disappointed, but he went ahead and paid for me. It is important to also say that, within few months, Constable Endurance and I became very close friends.

He admired the very talent Mr Jallow was talking about and would even invite me to lunches at his apartment in the barracks. He was one funny cop, but also hardworking.

We walked on the red clay ground to meet Saul Njie. He met us right at the door, seconds before he would have walked into the fenced field to take his seat in the commentary box situated at the northern flank of the field.

Mr Jallow told Saul in Wollof, “This is the boy I have been telling you about,” and Saul replied, “Yes, indeed, Saidou Sowe and many people have been telling me about him.”

Saul Njie turned around and looked at this big headed, skinny, young boy and asked me in Wollof, “NYEME NGA MA,” which translated as “Do you think you can take me on?”

Well, this shy boy held his own. I looked him straight in the face and said emphatically “YES!” After that brief encounter, I had a sigh of relief for having finally met my idol. I had the feeling the union was going to be great and beneficial to me. I still recall him telling me he was not going to look at me as a commentator but as a son, and, to this day, I regard him as a dear father. In fact, even his youngest daughter, Matty, thought she and I were of the same mother and father.

After our brief exchange at the door of the field, Saul proudly led me to the commentary box with a look on his face that said, “I have discovered a gem.”

He introduced me to three men known as the technical backup: Ousman Njie, Andrew Goffna and, a short funny guy from Bakau named Ebrima Sidibeh, who I became close to from that first meeting until I left the shores of The Gambia.

Two other men were already seated there: Pap Saine and Deyda Hydara. Pap Saine, who wrote the Forward on this book, is currently proprietor of one of Gambia’s leading newspapers, The Point.

At that time, he worked at a private Swedish owned Radio station, Radio Syd, just a kilometer outside the capital, but also doubled as a correspondent for Reuters and other French media outlets.

Deyda Hydara was his colleague from Radio Syd and a correspondent for Agency France International. Some years back, he was gunned down in the streets of Serrekunda by unknown gunmen and, to this day, no one has been apprehended for his mysterious assassination. Right away, I clicked with all on the team and they were extremely glad to see a young boy join them. Deyda, as gracious as he always was, made arrangements for me to join Tunde Thomas at 2 p.m. every Saturday on Radio Syd to be a contributor in their weekly sports program, for which I will be eternally grateful.

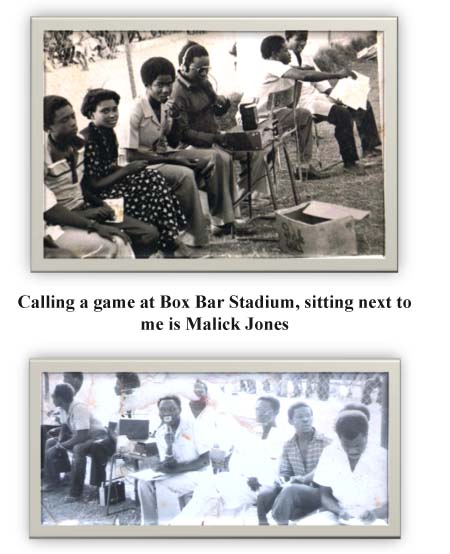

I sat gingerly next to Saul, in my usual routine, memorizing his every word until halftime when he introduced me to the whole country in the following words, “I am pleased to inform our listening audience that with me in the commentary box is fourteen-year old Young Tijan Ceesay who has joined our commentary team and will do some ball to ball commentary in the second half.”

After hearing these words, I became intimidated and started shivering, thinking of what I was about to embark on. Little did I know that I was also making history as the youngest football commentator in Africa at the time.

Five minutes into the game, I heard the seven words that would change my life forever, “Young Tijan Ceesay, it’s over to you!” Scared to death, I took the microphone from Saul without even saying thank you Saul and went straight into action and the first words I uttered were: “Here comes Abdoulie Jagne, standing hands akimbo and any minute will clear his lines for Real De Banjul.”

For the next five minutes, I called the game and I could see the pride in Saul’s face while those with radio sets at the spectator stands were all clapping for the new gem in Gambian football.

At the game’s end, I vividly recall his game summary. Saul Njie said: “That’s the way it is from Box Bar Stadium, for Pap Saine, Deyda Hydara, Andrew Goffna, Ousman and Ebrima Sidibeh on the technical backup and, of course, Young Tijan Ceesay. This is Saul Njie sending you back to the comforts of our studios at Mile Seven.”

Then came a sweet angelic voice from the main studios, the voice of veteran broadcaster Joy Coker, who then said, “Thank you very much indeed Saul. This is Radio Gambia in Banjul. You were listening to a live coverage of the football game at Box Bar Stadium between Real and Wallidan. Coming up next is the latest bulletin of the national news in English, Wollof and Mandinka.”

I then had a few words with Saul who invited me to his house a few blocks from the stadium where I met his wife Ida Njie, who would later become a second mother to me. Of course, I proceeded to go see my girlfriend at the time and, yes, I had my first kiss that day! She too was proud of her boyfriend. What a difference five minutes of air time on national radio made.

The following day I went to school, but it was no ordinary day. Every student was proud of me and the words of congratulations and best wishes were not short. The vice principal at the time, Fr. Joseph Gough, invited me into his little office down the hall and told me how proud he was of me and he appointed me the sports reporter for the school quarterly, Sunu Kibaro, a position I held until I graduated from high school.

The Irish Priest would not stop. During the biggest events in the school calendar, which included speech and prize giving ceremonies attended by the Gambian president; Fr. Gough ensured that there was a segment for me to speak.

Of course, this was not popular with some members on the teaching staff, but they could not do anything about it, which would not help my case, because some hated my guts to be straightforward.

Saul and I became closer, with the father-son relationship growing stronger by the day.

He encouraged me to read more and to practise writing. I would heed his advice and continued to work harder.

As time went on, Saul gave me bigger assignments and my stardom continued to grow, which really did not sit well with some top officials at Radio Gambia.

At the time, I was young and had no idea of jealousy and infighting; two common Gambian phenomena, which were nonexistent among my peers, but it did not take long for me to learn that it was all about Saul Njie.

Most of his colleagues were jealous of his work and wide popularity and it was not going to be any different for his student.

There were even some who could not hide their displeasure when they saw me sitting in the commentary box, let alone speaking over Radio Gambia where I was not a member of staff.

Did I have a quick taste of infighting at an early age? You bet I did, and, to this day, I attribute it to be the one reason why Saul never wanted me to take a full time job at Radio Gambia after completing high school.

As time went on, I grew in the team and Saul appointed me to be the statistician on game days and the person responsible for research. Being responsible for research was the greatest experience of all, because it gave me an opportunity to visit with teams at their respective headquarters to research their histories. That paid off big time because, through this, I was able to put this work together.

On game days, I submitted my reports to Saul and I always beamed with pride whenever he said, “Young Tijan Ceesay paid team X a visit at their camp and compiled the following.”

At halftime and game’s end, he would invite me as a statistician on the air to announce how many shots each team took, corner kicks, fouls, offsides, etc. This was something I looked forward to every week.

In 1978, Bora Mboge, a senior broadcaster, joined the commentary team and began working with Saul.

Mboge would be in charge when Saul travelled. When Saul was away, I was not given a chance to come on air, which, to this day, I have been given no explanation, even though Bora and I had an excellent relationship, but that’s the way it was.

Oreme Joiner, now a senior banker in The Gambia, Silas Maclean Jones, and Nana Grey Johnson also joined the team at Saul’s invitation and served as game analysts.

A young broadcaster named Sam Allaba Jones joined the team in 1980. We clicked instantly and are extremely close friends to this day. He recalled our friendship at my wedding in 2004 when he told guests: “The microphone is what binds Tijan and me.” Indeed, Sam, now Malick, was quite receptive of me and gave me the opportunity to call games when he was in charge. It would not stop there. On my return to The Gambia, he invited me to be a co-host of his daily sports show on Gambian television, for which I am eternally grateful.

In 1984, I travelled to Freetown with Saul to call The Gambia’s game against Sierra Leone in the Africa Cup of Nations qualifiers. I had no idea that kids in Freetown my age were already aware of me. I was in awe when we arrived at our lodging at the Siaka Stevens Sports Stadium on Syke Street across from Ascension Town cemetery in downtown Freetown. They camped out in numbers to meet me. I had no idea of the celebrity status that was accorded me in the West African country. Saul and I relayed that game back to Banjul to a disappointed nation that was expecting a victory, but The Gambia lost two nil.

I still recall when I returned to Banjul, one fan telling me, “Listening to you from Freetown, I did not know if we were losing the game.”

Well, indeed, I had to put a lot of energy and confidence in my game calling no matter what, because Saul stressed that and he demanded nothing but excellence, for that I was proud.

At game’s end, fans converged in the hundreds at the stadium hostel where we stayed to meet the school boy commentator.

While they were happy to see a young boy my age up there in the commentary box, the Gambian captain at the time, Baboucarr Sowe aka Laos, who was my roommate in Freetown, told me not to venture outside and I complied.

The next morning, I was disappointed to learn that the fans were dispersed via teargas by the Special Security Division (SSD), for what reason I still don’t know.

As I continued to work with Saul, our relationship grew stronger to the point that I had my lunch and dinner at his residence every day.

He continued to encourage me as a father figure and he even went on to serve as coach of our high school debating team which beat St Joseph’s High School in that historic debating final sponsored by the Nigerian Embassy in Banjul.

The team made up of Lamin Manjang, James Jegan Bahoum and myself used a great strategy devised by Saul and beat Hawa Kuru Sisay, a dear sister and her team.

Fr. Gough’s decision to bring Saul Njie in to coach our debating team, did not sit well with some teachers in our English department and, yes, I had to pay the price with being ridiculed in class.

I can recall when I tried to be creative in one assignment profiling the President. I started my essay with, “Boom, Boom, came the drumming of the tabala on May 16th, 1924, announcing the birth of Saikou Almami Jawara in Barajali,” My English teacher wrote the following query, “From which brochure did you copy this or did you get this nonsense from Saul Njie?” Well, I did not answer it, but today I will, “Teacher, I got it from the creative writing that Saul was teaching me and that you were not.”

In June 1983, I finished high school with no intention of trying to get a job immediately.

However, in August of that year, a former schoolmate of mine and close friend, Hussein Lucien Thomasi, who was, at the time, working for The Gambia Information News Agency, would send a message that the Director of Information and Broadcasting, Mr Swaebou Conateh, wanted to see me at his Apollo Hotel Annex office in Half Die.

A few days later, I went to see Mr Conateh, a well accomplished writer himself, who offered me a job as the Sports Reporter for The Gambia News Bulletin and as an Assistant Trainee Journalist.

I happily accepted the job. I was placed under the custody of a tall and calm colonial trained journalist, Mr Abdoulie A. Njai, who, at the time, was the Editor for the bulletin.

I became a fully accredited journalist and continued to be part of the commentary team and assisted Saul until December 1984 when I left for good.

In early 1985, Saul left for a few months to study in Germany. My welcome in the box at the new Independence Stadium was nonexistent, so I concentrated on the Bulletin and on calling games for Hussainou MM Njie, by far the greatest all time contributor to and financier of Gambian sports, who had purchased video equipment to document history, which meant that I had my own gig, which was really fun, because it gave me an opportunity to be me and get out of Saul’s shadow, which he had so wanted for the longest time.

In tandem with that, I was the managing editor of the first football daily in Gambian history, Zone Two Cabral Daily, which was specifically set up to cover the Zone Two Amilca Cabral football tournament held in The Gambia in 1985.

During this tournament, the commentators from Radio Gambia, without doing sufficient research on goal differential when Gambia and Sierra Leone were virtually tied on points, erroneously reported that Gambia was out of the competition, which was not the case and I made that story my lead story the next day with the caption, “RADIO GAMBIA AND ITS COMMENTATORS.”

In that piece I said, the radio commentators without any fact checking decided to tell the Gambian public that The Gambia was out of the tournament, which I called a disaster at the time.

This did not sit well with my former colleagues and an eight-year marriage was sent to the ash heap of mortality. With the elder Saul Njie away in Germany, reconciliation was not a word of choice and that was it for me and football commentary in Gambia.

By and large, I still believe, deep down in my heart, that Saul Njie is the best thing that ever happened in Gambian broadcasting.

I am proud that the same training and knowledge he passed unto me, I was able to share with young future broadcasters like Lawyer Mai Fatty and Alagie Ceesay.

I could not be more proud of my relationship with Saul, but I’ll leave the last word with his second daughter, Matty Njie, who recently said to someone whom she had no idea was my distant aunt, “Growing up, until 1987, I thought Tijan and I belong to the same Mother and Father. It was only when we got to Abidjan that I asked my Mom, why Tijan was not with us and she told me, Tijan is in the States and explained to me that, in fact, Tijan was like my Father’s adopted son.”

Well, that explains it all. It was not just sitting next to him at Box Bar Stadium. Saul was everything I asked for.

Note… Tijan’s Book can be purchased at Amazon and will be available on sale in The Gambia pretty soon. Contact The Point to book a copy.