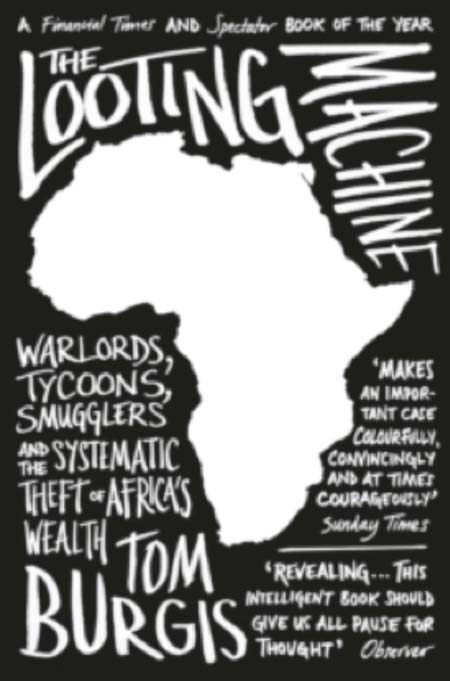

The

Looting Machine, warlords, tycoons, smugglers and the systematic theft of

Africa’s wealth, Tom Burgis, Collins, 2016, 324 pages

This

book should be a timely read for those who will be entrusted with the task of

probing the whereabouts and whereof of the alleged loot of ex-president Jammeh.

Since our despot fell from power and fled into exile, there have been a lot of

media reports on how the rosary-carrying despot allegedly siphoned off millions

from our coffers. If true, this new book by a prize winning Financial Times

reporter Tom Burgis, should explain why it is so easy for bad rulers to steal

from their impoverished people.

This

book is a searing exposé of the global web of traders, bankers, middlemen,

despots, tyrants, corporate raiders, marabouts, mistresses and all kinds of bad

and nasty wheeler-dealers who steal Africa’s wealth. In this book, the author

contends that national treasury looters work in tandem with a wide web of

conspirators to enable them make Africa poor. He also explains how Western

multinationals, Chinese corporations, (p. 81, 111) and Asian mafias all are

working with corrupt looters to steal Africa’s resources. There are secretive

networks at work to steal from Africa.

In

chapter one, the author explains how a tiny clique in Angola has successfully

siphoned all the proceeds from the once booming oil and diamond mining

concessions to feather their own nests, leaving the ordinary Angolan poorer.

The few families around the President Dos Santos ‘embarked on the privatization

of power’ and took ‘personal ownership’ of Angola’s wealth (p.10). As a result,

according to Burgis, Dos Santos’ daughter became Africa’s first billionaire in

2013! Indeed, between 2007 and 2010 the Angolan elite stole USD32 billion!

Equally, telling is the fact that the rulers are able to steal only after

inflicting fear into the people so that no one dares ask questions, while the

systematic looting of the resources takes place. Gambians will also be familiar

with this: create fear and terror first, and then start the looting (p.12).

In

chapter 5, the author narrates the sickening corruption in Guinea under the

late unlamented tyrant Lasana Conte. As he lay dying in 2008, he still entered

into a contract with shady Western companies to exploit Guinea’s rich bauxite

deposits. His youngest wife got a bribe of USD 12 million from this company so

that her dying husband will agree to the deal (p.109). In Guinea, what belongs to the state belonged

to Conte!

The

author further reveals that the looting of Africa’s resources wreaks havoc not

only on the economy but also on the fragile ecosystem and environment. He cites

how oil companies have poisoned the once serene creeks of the Niger delta in

Nigeria such that entire communities have been turned into toxic crannies where

nothing thrives, and everything is sick. It is apparent that Africa has

30% of the world’s minerals and oil; 14%

of the world’s population and has 43% of the world’s poor. ‘Why is the richest

continent also the poorest’? This book answers the question very well. It is

highly recommended read for anyone interested in the fate of Africa as a

continent.

Available

at Timbooktoo, tel 4494345

Read Other Articles In Article (Archive)

GCCI prepares for annual dinner, award

Feb 15, 2010, 2:11 PM