Human rights are the rights a person has simply because he or she is a human being.

Human rights are held by all persons equally, universally, and forever.

Human rights are inalienable: you cannot lose these rights any more than you can cease being a human being.

Human rights are indivisible: you cannot be denied a right because it is “less important” or “non-essential.” Human rights are interdependent: all human rights are part of a complementary framework. For example, your ability to participate in your government is directly affected by your right to express yourself, to get an education, and even to obtain the necessities of life.

Another definition for human rights is those basic standards without which people cannot live in dignity. To violate someone’s human rights is to treat that person as though she or he were not a human being. To advocate human rights is to demand that the human dignity of all people be respected.

In claiming these human rights, everyone also accepts the responsibility not to infringe on the rights of others and to support those whose rights are abused or denied.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Rights for all members of the human family were first articulated in 1948 in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Following the horrific experiences of the Holocaust and World War II, and amid the grinding poverty of much of the world’s population, many people sought to create a document that would capture the hopes, aspirations, and protections to which every person in the world was entitled and ensure that the future of humankind would be different. See Part V, “Appendices,” for the complete text and a simplified version of the UDHR.

The 30 articles of the Declaration together form a comprehensive statement covering economic, social, cultural, political, and civil rights. The document is both universal (it applies to all people everywhere) and indivisible (all rights are equally important to the full realization of one’s humanity). A declaration, however, is not a treaty and lacks any enforcement provisions. Rather it is a statement of intent, a set of principles to which United Nations member states commit themselves in an effort to provide all people a life of human dignity.

Over the past 50 years the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has acquired the status of customary international law because most states treat it as though it were law. However, governments have not applied this customary law equally. Socialist and communist countries of Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Asia have emphasized social welfare rights, such as education, jobs, and health care, but often have limited the political rights of their citizens. The United States has focused on political and civil rights and has advocated strongly against regimes that torture, deny religious freedom, or persecute minorities. On the other hand, the US government rarely recognizes health care, homelessness, environmental pollution, and other social and economic concerns as human rights issues, especially within its own borders.

Every woman, man, youth and child has the human right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, without discrimination of any kind. Enjoyment of the human right to health is vital to all aspects of a person’s life and well-being, and is crucial to the realization of many other fundamental human rights and freedom.

The WHO Constitution was the first international instrument to enshrine the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health as a fundamental right of every human being (“the right to health”). The right to health in international human rights law is a claim to a set of social arrangements - norms, institutions, laws, and an enabling environment - that can best secure the enjoyment of this right.

It is an inclusive right extending not only to timely and appropriate health care but also to the underlying determinants of health, for example access to health information, access to water and food, housing, etc.

The right to health is subject to progressive realization and acknowledges resource constraints. However, it also imposes on states various obligations which are of immediate effect, such as the guarantee that the right will be exercised without discrimination of any kind and the obligation to take deliberate, concrete and targeted steps towards its full realization.

Right to health

The right to health is the economic, social and cultural right to a universal minimum standard of health to which all individuals are entitled. The concept of a right to health has been enumerated in international agreements which include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

However, there remains some international variation in the interpretation and application of the right to health due to considerations such as how health is defined, what minimum entitlements are encompassed in a right to health, and which institutions are responsible for ensuring a right to health.

Health equity

The General Comment also makes additional reference to the question of equity, a concept not addressed in the initial International Covenant. The document notes, “The Covenant proscribes any discrimination in access to health care and underlying determinants of health, as well as to means and entitlements for their procurement.” Moreover, responsibility for ameliorating discrimination and its effects with regards to health is delegated to the State: “States have a special obligation to provide those who do not have sufficient means with the necessary health insurance and health-care facilities, and to prevent any discrimination on internationally prohibited grounds in the provision of health care and health services.” Additional emphasis is placed upon non-discrimination on the basis of gender, age, disability, or membership in indigenous communities.

Relation to other rights

Like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the General Comment clarifies the interrelated nature of human rights, stating that, “the right to health is closely related to and dependent upon the realization of other human rights,” and thereby underscoring the importance of advancements in other entitlements such as the rights to food, work, housing, life, non-discrimination, human dignity, and access to importance, among others, towards the recognition of the right to health. Similarly, the General Comment acknowledges that “the right to health embraces a wide range of socio-economic factors that promote conditions in which people can lead a healthy life, and extends to the underlying determinants of health.” In this respect, the General Comment holds that the specific steps towards realizing the right to health enumerated in Article 12 are non-exhaustive and strictly illustrative in nature.

Responsibilities of states and international organizations

Subsequent sections of the General Comment detail the obligations of nations and international organizations towards a right to health. The obligations of nations are placed into three categories: obligations to respect, obligations to protect, and obligations to fulfill the right to health. Examples of these (in non-exhaustive fashion) include preventing discrimination in access or delivery of care; refraining from limitations to contraceptive access or family planning; restricting denial of access to health information; reducing environmental pollution; restricting coercive and/or harmful culturally-based medical practices; ensuring equitable access to social determinants of health; and providing proper guidelines for the accreditation of medical facilities, personnel, and equipment. International obligations include allowing for the enjoyment of health in other countries; preventing violations of health in other countries; cooperating in the provision of humanitarian aid for disasters and emergencies; and refraining from use of embargoes on medical goods or personnel as an act of political or economic influence.

Convention on the Rights of the Child

Health is mentioned on several instances in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). Article 3 calls upon parties to ensure that institutions and facilities for the care of children adhere to health standards. Article 17 recognizes the child’s right to access information that is pertinent to his/her physical and mental health and well-being. Article 23 makes specific reference to the rights of disabled children, in which it includes health services, rehabilitation, and preventive care. Article 24 outlines child health in detail, and states, “Parties recognize the right of the child to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health and to facilities for the treatment of illness and rehabilitation of health. States shall strive to ensure that no child is deprived of his or her right of access to such health care services.”

Human right to health care

An alternative way to conceptualize one facet of the right to health is a “human right to health care.” Notably, this encompasses both patient and provider rights in the delivery of healthcare services, the latter being similarly open to frequent abuse by the states. Patient rights in healthcare delivery include: the right to privacy, information, life, and quality care, as well as freedom from discrimination, torture, and cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment. Women, sexual minorities, and those living with HIV, are particularly vulnerable to violations of human rights in healthcare settings.

For instance, racial and ethnic minorities may be segregated into poorer quality wards, disabled persons may be contained and forcibly medicated, drug users may be denied addiction treatment,

Provider rights include: the right to quality standards of working conditions, the right to associate freely, and the right to refuse to perform a procedure based on their morals. Healthcare providers often experience violations of their rights. For instance, particularly in countries with weak rule of law, healthcare

Providers are often forced to perform procedures which negate their morals, deny marginalized groups the best possible standards of care, breach patient confidentiality, and conceal crimes against humanity and torture. Furthermore, providers who do not oblige these pressures are often persecuted. Currently, especially in the United States, much debate surrounds the issue of “provider consciousness”, which retains the right of providers to abstain from performing procedures that do not align with their moral code, such as abortions.

For further information visit The Gambia Human Right Agency, email to azadehhassan@yahoo.co.uk, or text to 00220-7774469/3774469 from 3-6 working days.

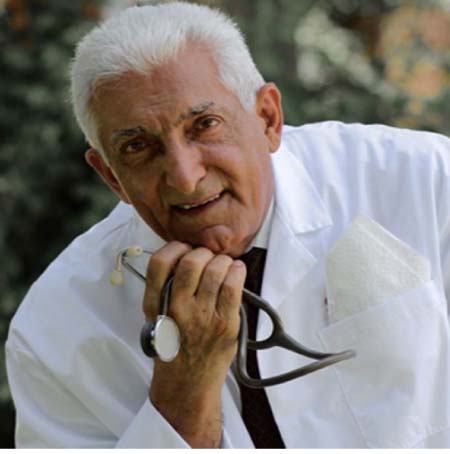

Author DR Hassan Azadeh Senior Lecturer at the University of the Gambia, Senior Consultant in Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Clinical Director of Medicare Health Services