A

victim of human trafficking has told stories of how her employers subjected her

to abuse and exploitation during her years of work in Lebanon.

“They

used to call me ‘dog’,” she said.

Istaou

(not her real name) is a 27-year-old school dropout who spent years looking for

a job in The Gambia without success. In

2014, she was advised by her friend, another young Gambian woman based in

Kuwait, to go to Lebanon for work.

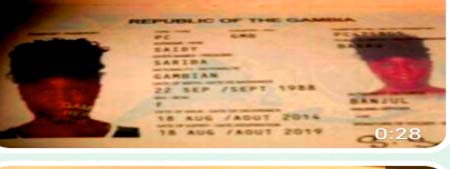

Isatou

agreed and began raising funds to pay an agent in The Gambia, who facilitated

her travel and got them employment as maids in Lebanon. They are employed by housewives of rich men

they call “mistresses” to take care of their domestic chores.

In

The Gambia, Isatou would not do such a job, given her education. She once worked as a marketer of Sim cards

and cell phones of one of the GSM companies in The Gambia. At one point, she was also ticket seller for

a lottery company in the country.

Her

job in the eight-bedroom, two-storey building home in the Lebanese capital of

Beirut includes bathing the kids, cleaning the rooms, pavements and backyard,

scrubbing the tiled floors, wiping window glasses, furniture and the interior

walls.

“I

also clean the dining room and the plates after every meal. Sometimes, they wake me from sleep at 2 a.m.

just to do this,” she said.

Prior

to her going to Kuwait, she was a simple town girl, who went to school and has

completed junior secondary education.

She dropped out in the first year of her senior secondary schooling due

to teenage pregnancy, even though she was a good student in English, Geography,

and Home Economics.

Despite

Isatou’s dreams of going to university one day, it was her ageing mum who ended

up in a wheelchair after she heard the news of her daughter’s pregnancy in the

eighth grade. She has had stroke. Her dad, also ageing and now a retired night

watchman, has neither the means nor the strength to support Isatou to return to

school after she delivered a son.

She

ended up joining the teeming number of young school dropouts searching for jobs

in an already saturated market of joblessness.

But with no certified skills other than her basic secondary school

certificate, her plans increasingly became a far-fetched dream.

$175

per month pay

She

was offered a $175 pay per month. Isatou

saw this as a higher offer than what she managed to earn in two of her jobs in

The Gambia. Her employers would provide

accommodation, feeding and welfare. She

didn’t know she will be sleeping on a three-inch thick mattress on a bare

concrete floor of a room behind the family’s house for almost three years.

“I

saw it as an opportunity to experience travel, at least once in my life. I was promised security, welfare and

reasonable pay. So I took the offer,”

she explained.

In

early 2014 when she came to Beirut, a dollar was D37. With $175, she was making about D5,000 per

month.

This

was enough to pay for the family’s rent, buy a bag of rice and a week’s fish

money for a family of seven – now excluding Isatou. If she is to save anything from this amount,

it means she will cut off some of those family expenses.

She

needed to maintain her expenses to minimum if she has to save anything from her

$175 monthly pay. Or, send some money to

her family in Gambia each month, as she promised her father and aunty Binta,

who was now in charge of bringing up Isatou’s young son.

Her

mum and the scars

Her

mum passed away two years ago. She could

not survive the stroke, and Isatou still spends sleepless nights crying when

she thinks about her mum. Her aunty

Binta, notorious for her love for money, has taken the role of making decisions

on Isatou and her siblings’ lives.

In

her mid-forties, Binta has been with their family after her divorce from her

marriage since Isatou was in the eighth grade. It was not surprising she encouraged her to travel and work in Kuwait.

“Would

it not be lovely to travel to the land of the Arabs and experience new things?”

Isatou recalled her aunty telling her.

That

was why the first time her mistress’ husband raped her while the wife and the

rest of the family were asleep, she cried so hard and regretted why she got

pregnant while going to school.

“She

would not have encouraged me to go away to work in a foreign country where I

would be helpless,” Isatou recalled proudly of her mum.

Now

all she wants is to finish paying up her contract years that would have made up

her employer’s investment on her travels from Banjul to Lebanon. It is between $2,000 to $3,000.

“They

do not allow me to eat with the family neither am I allowed to answer the

door,” she said.

The

rapes, the insults and the battering became routine. Still she cannot leave. Her passport is confiscated. She works very long hours without rest. She gets no medical care or other welfares as

promised. It is a trap, she admitted.

Isatou

has become a slave and she cannot free herself.

It even makes her cry more when she goes to bed after exhaustive hours

of work.

“I

will be free one day. I will return home and secretly nurse the scars this work

in Lebanon has inflicted on me,” she said.