The month of April is Jazz Appreciation Month in the United States. Each year during this period, Jazz is celebrated throughout the United States in Communities, Schools, Concert Halls, and Night Clubs and in the street.

Lectures are given, Concerts are held,

Films are shown and many activities are staged to promote and nurture the

appreciation of Jazz. The history of Jazz is endless and its influence has

reached all corners of the globe. Here in the Gambia, we continue to do our

little bit to promote jazz music and jazz appreciation.

In previous notes we observed that the

piano is the fundamental instrument of jazz, and its use in the making of this

music has become standard and structured. The relationship of the piano to the

evolution of jazz music was more glaring and significant in Harlem, N.Y than

any other place during the development of jazz.

Harlem in the late 20’s was a society

balancing between two extremes. Only a few years back, Harlem was predominantly

a white neighborhood of European immigrants mainly of the Lutheran church. They

were descendants of the early Dutch settlers, and the name Harlem comes from a

city in the Netherlands with the same name.

In the years following the end of the

Second World War, the demographics of the neighborhood began to change with

African- American migrants from the south joining refugees from the overcrowded

tenements in midtown Manhattan.

Earlier on, in the late 20’s, 70% of the

real estate in Harlem was under black control and this bustling little city

within a city gave birth to what we now know as the Harlem Renaissance.

However, this development also brought

about another Harlem less glamorous and less fortunate. It is true that the

Harlem Renaissance created an ideology and a cultural context for jazz, but

what is greatly underrepresented, is the Harlem of “rent parties” and the

underground economies which created music.

Rent parties were a special passion for the

community but their very existence was avoided or barely acknowledged by most

writers of the Harlem Renaissance. The emerging black middle and upper classes

were ambivalent about vernacular elements of African-American culture and at

times explicitly hostile towards it.

Many great jazz notables such as Duke

Ellington and Cab Calloway got their start in the business in the so-called

speakeasies of Harlem which was the battleground of two visions of black

artistic achievement. For while there was the Harlem of literary aspirations,

there was also the Harlem of Jazz and Blues.

The piano was oftentimes the battleground

of these visions of black artistic achievement, and was to Harlem what brass

bands had been to New Orleans. The Harlem stride piano was the instrument of

choice and stood as a bridge between the ragtime idiom of the turn of the

century and the new jazz piano styles that were evolving. The development of

boogie-woogie in the 20’s and 30’s which became more popular in the 40’s,

expanded the vocabulary of African-American piano and propelled the style to

its highest pitch as unaccompanied keyboard music.

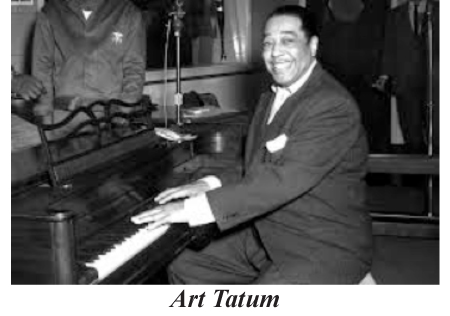

One of the most lauded masters of the

Harlem stride piano and indeed of boogie-woogie was a guy called Art Tatum. He

was a complex and controversial figure who was in many ways ahead of his time.

His vision of jazz music was initially inspired by the Harlem stride tradition,

which served as a foundation on which more complex musical superstructures

could be built.

He represented the finest flowering of the

Harlem stride tradition, but was also responsible for bringing the death knell

of this movement. For while developing his mature and unique style, he also

exhausted all the possibilities of the stride piano movement, forcing other

modern piano players that came later to move into other directions in order to

work their way out of the massive shadow of this seminal figure.

As a result, much of the musical vocabulary

that was developed by Tatum remains unassimilated by later jazz pianists.

Unlike the influence of Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, Tatum’s legacy

still sits in probate waiting for a new generation of pianist to lay claim to

its many riches. His role and contribution to the history of jazz is clouded by

his virtuosity as he was often criticized for his showmanship and gratuitous

displays of technique.

Tatum’s importance to jazz is due to his

advanced musical conception and also to his finger dexterity. His speed and

clarity of execution was unmatched and the harmonic components of his playing

were exceptional.

He was born in Toledo, Ohio, on October 13,

1910, far away from Harlem and the other centers of jazz. He was afflicted with

cataract in both eyes and underwent several operations in his youth which

eventually restored sight to one eye. Throughout his life, he only enjoyed

partial sight to his right eye and remained totally blind in his left eye.

However, as in the case with most blind musicians, Tatum compensated for his

blindness with an acuteness of hearing that at times seem preternatural. He

amazed his mother at the age of three when he picked out melodies on the piano

that he heard her sing at a choir rehearsal. Soon after that, he was imitating

jazz pieces he heard on radio and from other piano players. He attended the

Toledo School of Music, and while there, his mother and his teacher at the

school tried to steer him towards a career in classical music. He demonstrated

an extraordinary talent for playing concert music , but was already attracted

to jazz, and by the age of sixteen, he was busy working around Toledo while

performing on a local radio station.

The news of Tatum’s piano prowess was

starting to reach other parts of the jazz world, but the musicians in Harlem

were not prepared for the impact he made when he travelled to New York as an

accompanist to singer Adelaide Hall in 1932.

During those days in New York, the local

piano titans decided to test the mettle of the newcomer from Toledo. He was

invited to a nightspot in Harlem where the greatest masters of stride including

Fats Waller, James P. Johnson and Willie the lion Smith were ready to do

battle. They took turns playing and when it was Tatum’s time to play, he

dazzled them with a rendition of the famous song “Tea for Two” full of

harmonies and sweeping runs which left the audience speechless. He was followed

by James P. Johnson with his favorite song “Carolina Shout”, and then came

Waller with his song “Handful of keys”. After a few takes, the final verdict

was no longer in doubt. Waller would later say that Tatum was just too good and

had too much technique which made him sound like a brass band all by himself.

Johnson would also remark that when Tatum played “tea for two” that night, it

was the first time he ever heard it really played.

A few months later Tatum made his first

records which included two pieces he had played at that Harlem contest. Over

the next three decades, Tatum recorded frequently putting down over six hundred

tracks as soloist and bandleader.

However, despite the many virtues of his

music in the 1930’s and 40”s, Tatum is best remembered for a massive recording

project he did under the direction of producer Norman Granz towards the close

of his career. He recorded over two hundred tracks, mostly done in a single

take over the course of several marathon sessions.

In this body of work, he was featured both

as a soloist and in collaboration with other jazz greats including Ben Webster

and Roy Eldridge. In the early 1940’s, Tatum did some informal sessions with a

guy called Jerry Newman which showcased him in a more relaxed and uninhibited

mood at various nightspots in Harlem. Here, he could be heard playing,

accompanying and even singing the blues.

Those performances were playful but

majestic and breath -taking, giving credence to the view that Tatum was at his

best when playing “after hours”. In 1949 Tatum performed at the Shrine

Auditorium in a memorable concert where he astonished the audience doing

double-time work on the song “I know that you Know” playing at a tempo of well

over four hundred beats per minute.

Tatum was often criticized for having a

limited repertoire of mainly sentimental and popular ballads with preference

for ornamenting the melody of the piece rather than constructing original

improvisations. In spite of all the criticism, Tatum’s legacy is rich and full

of accolade. In November 1956, a short while after finishing the recording

project with Granz, he died in Los Angeles.

In 1985 a survey of jazz pianist, placed

Tatum comfortably on top, suggesting that despite the passing of decades, and

the changing tastes with the emergence of new masters of the keyboard, Tatum

had lost none of his power to astonish, inspire and at times dismay other

practitioners of the art.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article as

we look forward to celebrating Jazz Appreciation Month this April. You can also

listen to Jazz on the radio on City Limits Radio every Saturday at 10pm. This

piece is in memory of the late Bishop Telewa Johnson who was an avid jazz lover

and a supporter of this column.