An Address to The First Class of Students of The Gambia Law School at a Dinner at The Paradise Suites Hotel on Friday 31st August 2012

My Lord Chief Justice and Chairman of the General Legal Council

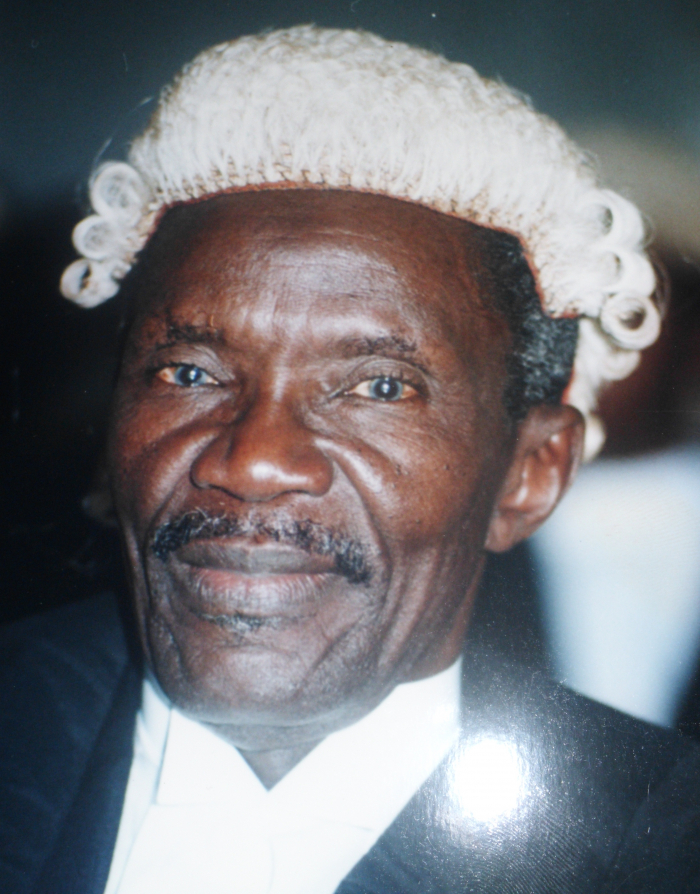

Lord Justice Raymond C. Sock/Director General of The Gambia Law School

Lord Justice J. Wowo, President of The Gambia Court of Appeal

Honourable Judges of the High Court

Hon. Justice Lamin Jobarteh, Attorney General and Minister of Justice

Lecturers, Staff and Students of The Gambia Law School

Distinguished Guests

Ladies and Gentlemen

IT IS, to me, always a matter of great pride and satisfaction that I was a member of the Steering Committee for the Establishment of the Law Faculty of The University of The Gambia, and not only amongst the first lecturers, but was also given the honour and distinction by the Vice Chancellor and academic community of the University to deliver the Inaugural Lecture to you, The First Class of Law Students of the University, in these same fantastic settings of this truly Paradise Suites Hotel on 22nd August 2007. Our subject on that occasion was “Legal Reasoning: The Evolutionary Process of Law”. My first interaction with the University, however, was on the invitation of the Dean of Clinical Sciences of The Faculty of Medicine & Allied Health Sciences to deliver a lecture on “The Legal Aspects of Medical Practice” to the First Class of Students of The School of Medicine in July 2003.

It was only on 17th July 2006 when the Sheering Committee for the Establishment of the Law Faculty held it inaugural meeting at the Conference Room of the Ministry of Education and barely six years later we are here, today, at dinner celebrating the first successes of our efforts in the development of legal education in The Gambia.

Our meetings moved to the Chambers and under the chairmanship of the Honourable Attorney General and Minister of Justice, Sheikh TijanHydara, and later to the office, and under the chairmanship, of the Vice Chancellor of the University, Professor Andreas Stiegen. His Lordship Emmanuel Akomaye Agim was an active member of the Steering Committee and at times chaired our meetings. Mr. Justice Emmanuel Fagbenle, Director of Public Prosecutions, as he then was, was also a member of the Committee and so was Mrs. Isatou Jallow-Sey, who later became the Co-ordinator of the Law Programme.

These were exciting times and exciting meetings when we discussed whether to have a three year or four year LL.B degree programme, the subjects and content of the courses to be followed from the first year to the final year, leading either to a general or an honours degree, the qualification for admission, the interview and selection of most of you, the first law students; the qualification for appointment, the interview and selection of those who, my good friend, Dr. Henry Carrol calls “Founder Lecturers”, like Dr. Carrol himself, Gaye Sowe and my humble self.

Four years later, in September 2010, I was given the singular honour and privilege of being appointed by the General Legal Council as “Consultant for the establishment and operation of the Gambia Law School and the preparation of the admission requirements, study curriculum, and programme of training of law graduates for qualification as barristers and solicitors of The Supreme Court of The .Gambia”. It is most gratifying therefore that I am being invited again to participate and be so closely associated with you, the First Class of Law Students of the University of The Gambia and now the First Class of Students of The Gambia Law School.

On the invitation to give this address at this august dinner, the Director General of the School, The Honourable Justice Raymond C. Sock was kind enough to say that I was at liberty to speak on any topic of my choice. I am touched by the gesture, humbled by his kind words and sentiments and, of course, delighted to continue to be part of you all, the bones and sinews of The Gambia Law School.

In his address to the Armitage High School Alumni Association on “The Dilema of the African Intellectual” in January 1977, Professor Lamin Sanneh, a distinguishes Gambian, an eminent scholar and D. Wills James Professor of History and of Missions and World Religions at Yale University – the first non-American to hold such a high and rear academic position – and also Chairman of The Yale Council on African Studies and Fellow of Trumbull College, told us about the story of a man who was invited to address a gathering of distinguished guests “O, my people”, he began “do you know what I want to talk to you about?” They all answered with a unanimous chorus: “No”. Well, then” he rejoined, “there is no need for me to say anything to people who are ignorant”, and promptly left the meeting hall.

On a second invitation he asked the same question. The people considered it for a while and decided that, since a negative reply on a previous occasion produced no results, they had better return an affirmative answer. “Yes”, they said. “Well, then”, the lecturer added, “there is no need for me to tell you anything since you know it all, already”. He departed from the scene.

The third time they invited him he put the same question to his rather battled audience by now. This time they consulted one another quickly and decided on a non-committal answer. On two previous occasions they had achieved nothing by answering “no” and “yes” each time. So they said to the lecture: “Some of us do know and some of us don’t”. The speaker retorted, “Let those who know tell those who don’t” and again left the audience chamber.

A salutary precedent, Mr Chairman, for all after dinner speeches but one which, I hope, we need not follow in our particular case tonight.

The moral of that story however, is relevant to us. The most valuable knowledge is that which grows out of our experience and is thus capable of transforming our condition by the power of the interior light. To be completely ignorant is to be devoid of the capacity to reactivate that light. Conversely, to claim total illumination is to persist in a boast without a corresponding progress into true knowledge. Acquiring worthwhile knowledge is a task of mutual help as much as self-help. “Let those who know tell those who don’t”.

My Lord Chief Justice, My Lords, Honourable Attorney General, Director General, Distinguished Ladies and Gentleman the subject of my address this evening shall be “The Road to Justice: Lord Denning, Master of the Rolls 1962 – 1982”.

In 1967, as a student at University for the combined BA/LLB programme some 45 years ago, I was required in the Legal System course, to review two books. My first review was of the book “Much In Evidence “ by Henry Cecil and the second, “The Road to Justice” by Lord Justice Sir Alfred Denning, as he then was, and later the legendary Lord Denning, Master of Rolls.

“The Road to Justice” is only 118 pages and was published by Stevens, London, in 1955. I have lost count of the number of times I have read this book and each time I did I derived enormous pleasure and great profit from it until I lost it many years ago when I lent it to a fellow student who would not return it … thus reminding me the wise words of a modern Socrates that “It is only fools who lend away good books, and only fools who return them”. I have chosen my review of this book and the author as the subject of my address to you at this august gathering, if only to remind myself of it and, perhaps more importantly, to recommend it as essential reading to all persons interested in the study and practice of the law and especially to you at this formative stage of your professional legal career.

This remarkable little book, “The Road to Justice” is a collection of addresses given by Lord Justice Sir Alfred Denning, as he then was, during visits to South Africa, Canada and the United States of America. His aim, according to the preface, is “to indicate the principles which must be observed in any country if justice is to be done therein” and in this he, as is expected of a man of his scholarship and eminence in the legal profession, succeeds most admirably.

The first chapter of the book, appropriately called, “The Road to Justice”, deals with the morality of the law. Lord Justice Sir Alfred Denning challenges, at the outset, the facile assumption of those judges and lawyers who regard the law as something separate and apart from justice, who regard the courts not as the Courts of Justice but the Law Courts; in short, those who think that they are only concerned with what the law is, not with what it ought to be so that if this leads to an unjust result contend that it is a matter for parliament, not for them. He says that this is a fallacy as it is the judges and the lawyers who have made the law what it is – most of English law being judge – made law, and statute law drafted and interpreted by judges and lawyers – so that it is the judges’ and lawyers’ part of it that the injustices occur. “The legal profession, by its exponents in days past or in days present”, he says, “must account for every injustice done in the name of the law”.

Lord Justice Sir Alfred Denning also points out that judges and advocates who assume the fallacy that the law is an end in itself and regard it as a series of commands of what people should or should not do – or a piece of social engineering designed to keep the community running smoothly and in good order – are those who draw a clear and absolute line between law and morals or between law and justice and are not concerned with the morality or justice of the law but only with the interpretation of it and its enforcement. He says that judges and lawyers of this cast of mind overlook the reason why people obey the law which is not because they are commanded to do so, nor that they are afraid of sanctions or punishment but that it is because they recognise it as an obligation which, in turn, arises from their habits and respect for it, their participation in it, their moral obligation to maintain order, and, above all else, because of the moral quality of the law. This means that the law should be equal to justice! Defining justice as what the right –minded members of the community – those who have the right spirit within them – believe to be fair, the Learned Judge emphasises the great responsibility which rests upon judges and lawyers because it is they who represent the right – minded members of the community in seeking to do what is fair between man and man and between man and state and they can only do this by means of just laws justly administered.

Lord Justice Sir Alfred Denning also examines the judicial oath word by word to explain how this conception of the task of the judge and the lawyer finds its finest expression and significance in those holy words which require the Judge’s affirmation of his belief in God and true religion, that he will do justice not he will do law, to all manner of people, according to law, not injustice according to law, without fear or favour, affection or ill-will.

These words also enshrine the independence and impartiality of judges but Sir Alfred warns that such independence if it is not backed with justice turns to obstinacy and recalcitrance and that impartiality can result to distribution of injustice as well as justice, “Judges”, he says, “must execute, not law alone but law and justice”, and they must do so “in mercy”.

In this, Sir Alfred equates the close relation of the great precepts of law and of religion and, comparing these principles with the practice of law he points out that in too many respects the law is inadequate for the needs of today and regrets also that some judges and lawyers care too much for law and too little for justice, in such an extent that, instead of being, as they should be, men of spirit and of vision leading the people in the way they should go, and making the law fit for the times in which we live, they have become technicians – more concerned with – spelling out the meaning of words. Quoting John Bynyan in 1675, he admits that this is not new but asks that like Evangelists, we should not, in our progress in the law, rely over much on legality – on the technical rules of law – but ever to seek those things which are right and true for there alone will we find the road to justice.

He also points out that on this road one must remember the two objects to be achieved: firstly, that the laws are just, and the other, that they are justly administered and important as both are, the more important is the second because just laws, unjustly administered are worse than useless. This means that the administration of justice depends on the quality of the men and woman who are ready to undertake it as even harsh and unjust laws, if administered by just judges can be mitigated and alleviated without which a country cannot tolerate a legal system which does not give a fair trial. A fair trial, Sir Alfred emphasises, depends on the rule of law which upholds that no man is above the law, that there should be no sentence without a fair trial by an independent and disinterested, as well as impartial, judge according to law and justice.

Having defined his subject matter, the Learned Judge Sir Alfred goes on to discuss one broad theme in each chapter. The first of these themes is called”, The Honest Judge”. I am unwilling to attempt any kind of summary of his arguments because I fear that to summarise would he to distort. But I want to make it quite clear that the range of discussion is much wider than law. The chapter opens up with a great tribute to the Judges of England that, “if justice had a voice, she would speak like an English Judge”. Sir Alfred, however, points out that the only quality which the judges have to merit this tribute is that they, each and every one, seek to be fair, and see to it that every person coming before them has a fair trial. To this end he discusses the principles that make the honest judge. First, he must be absolutely independent. Judges must be regarded as standing between the individual and the state, protecting him from any interference with his freedom which is not justified by law. Sir Alfred, here illustrates very vividly, the historical course of the independence of the British Judge from the time of that great judge, Sir Edward Coke, to the present day: his tenure of office, freedom from arbitrary dismissal, his high salary – to ensure that the Bench shall command the finest characters and the best legal brains that can be produced – and the reason for “no promotion for judges” so that their decisions are not influenced by the hope for promotion.

To ensure a fair trial, the second principle is that the judge must have no interest him or herself in any matter that he or she has to try. He or she must be impartial because justice must not only be done but it must manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done.

The third principle is that the judge before he or she comes to a decision against a party, must hear and consider all that the parties have to say. In this respect a strong and independent body of advocates is an essential function of liberty. This also emphasises the significance of the system of legal aid.

Fourthly, a judge must act only on the evidence and arguments properly before him or her and on no other.

He or she must, fifthly, give reasons for his or her decision for in order that a trial should be fair, it is necessary, not only that a correct decision should be reached, but also that it should be seen to be based on reason and that can only be, if the judge him or herself states his or her reasons. If his or her reasons are at fault, they afford a basis for appeal and an appeal can be properly determined only if the appellate court knows the reasons for the decision of the lower court.

Finally, a judge should in his or her own character be beyond reproach. At this point Sir Alfred raises the moral question whether a previous offence should be a bar to the appointment of a judge. He found his answer in Plato who said more than 2000 years ago that it is not right for a judge to have a personal experience of evil doing. Knowledge, not personal experience should be his guide because as Plato says “vice cannot know virtue: but a virtuous nature, educated by time, will acquire knowledge of both virtue and vice”. Hence the issue is settled that a man or woman should not be appointed a judge if he or she has been found guilty of a grave offence against the law particularly if this is known as such public knowledge would destroy its confidence in the judge. Conclusively, Sir Alfred says that the difficulty of applying these principles, as for instance who is to say whether an offence is a grave one which carries reproach in the eyes of the people, is the responsibility of those who make the appointments and their good discharge of it.

The next theme is “The Honest Lawyer”. In this chapter Sir Alfred Denning discusses his charges against and the virtues of the honest lawyer. Sir Alfred states at the outset that “there are no honest lawyers left. The only honest one had his head off”. He also emphasises that “if there is anything more important than any other in a lawyer it is that he or she should be honest. He or she must be honest with his or her client. He or she must be honest with the court. Above all he or she must be honest with him or herself”. Applying the words of William Temple to the courts of law Sir Alfred also says of lawyers that “each side should state its case as strongly as it can” – that is the part of the advocate. “before the most impartial tribunal available”- that is the part of the judge. “with determination to accept the award of the tribunal” – that is the part of the ordinary man.

Sir Alfred goes on to make a number of charges against lawyers. Firstly, that they abuse the freedom of speech which is given to them. He gives some vivid illustrations of the deplorable conduct of the Bar both in the past and in present times. It means that there is still much to be desired to make the language of prosecuting counsel in keeping with the traditions of the Bar. He emphasises that the primary duty of a lawyer in public prosecution is not to convict but to see that justice is done and to this end he or she must realise his or her duty to be fair because the country expects it and judges require it. He or she must not press for conviction, his or her right of cross-examination must be exercised in a moderate and restrained manner; in short, tradition demands that he or she should act, not as an advocate to condemn the accused but as a minister of justice to see that he is fairly treated. Illustratively, Sir Alfred discusses what lawyers should and should not do and that the same standards apply in criminal and civil cases.

His second charge is that lawyers distort the truth for gain because as the paid mouth-piece of his or her client, paid to win the case for the client, if he or she can, the lawyer tries to do everything in his or her power to win, even to the extent of keeping back what may hurt his or her client’s interests. He says the lawyer should recognise his or her duty to his or her client along with his or her duty to the court – i.e. a duty to the cause of justice itself and, as such, must never suppress or distort the truth. In this he gives some vivid and illustrative instances of what the lawyer should do to resolve this conflict between his or her duty to his or her client and his or her duty to the cause of justice both before and during a trial in both criminal and civil cases. He also explains the need and urgency for the recognition and observance of this duty and the likely legal consequences and social effects for failing to do so.

The third charge is that lawyers run up costs: more concerned with their fees than with the interests of their clients; that they will advise their clients to go to law when they know or ought to have known he or she had best stay out of it; and that they run up costs in legal procedures and technicalities which could well be done away. Sir Alfred also explains the reason for the introduction of the system of legal aid, its abuse by lawyers and the social effects of such abuse or misuse especially in family relations and divorce cases. He also points out a number of illustrations including the likely temptation of a low-principled lawyer, who, actuated by his own interests for more fees, worries nothing about the likelihood of the client losing a case as well as an offer for settlement but advises the client to go ahead with a doubtful claim. He regrets the seriousness of this abuse or misuse of the legal aid system and of the lawyer’s duty to the client and emphasises that this duty should be put before their own interests and without deflection by the pursuit of private gain.

Having now done with the things which a lawyer must avoid, Sir Alfred turns to those which he/she must do – the virtues of the honest good lawyer. Firstly, he/she must have a command of the English language so as to put his/her client’s case clearly and strongly before the judge, because the very reason for employing an advocate is that he/she should present the case in the best possible light.

The second quality which becomes a lawyer is courage: courage to defend his or her client no matter how much public opinion is against the client, no matter how distasteful is the task, no matter how inconvenient to him or her, and no matter how small a fee. Sir Alfred traces this defence of liberty to Erskine who first vindicated it in the trial of Tom Paine on his book, “The Rights of Man”, and who also showed the way, in the celebrated libel case of the Dean of St. Asaph in 1784 which was one of the great steps in establishing the freedom of the press in England that when the duty of counsel to defend a person brings him into conflict with the Bench, tradition demands that he or she must, whilst showing every courtesy to the Bench, nevertheless take every legitimate point on behalf of the client.

The third virtue is courtesy. The lawyer must not only treat the judge with courtesy but must also treat the opponent as well as the witnesses with courtesy too. “This is good policy as many cases have been won by courtesy and lost by rudeness”, Sir Alfred points out. “Besides”, he says “it is also good manners, and as of all professions and particularly true of the Bar, “manners makyth man”. Discussing the consequences of discourtesy, Sir Alfred also explains the disciplinary measures taken by members of the Bar and the strict control applied by the Inns of Court. He also discusses the privileges of the Bar as well as their abuse and or misuse.

The fourth theme is “The Free Press” What is its proper role in a free society? How does it abuse this role and what part does it play in the administration of law and justice? Sir Alfred points out that a free press is an essential function of individual freedom in a free society. He also holds that newspaper reports in courts are the watchdog of justice and agrees with Jeremy Bentham that “the security of securities is publicity”. “Where there is no publicity”, he asserts, “there is no justice “, But he also criticises the abuses by the press of this freedom – “trial by newspapers.”, He points out how newspapers by printing hearsay at first or second hand freely, can poison the mental atmosphere of the entire community forever to make a fair trial impossible. He also condemns, as evil, the lawyers who take part in this publicity by holding press conferences and issuing press releases.

Sir Alfred explains and discusses the legal consequences as well as social effects of “trial by newspapers”:, misrepresentation of proceedings, libel on a judge, invasion of privacy, obscene publications and horror comics but also maintains, in his criticisms of the freedom of the press, the essential function of the right of fair criticism against the arbitrary use of power in a free society. He says that “too much freedom leads to the evils of trial by newspaper; obscenity, horror-comics, and the rest, but on the other hand, too much control leads to a servile press which tells the people only that which the party in power wants them to know. Better to have too much freedom than too much control: but better still to strike the happy mean” – and to this end he urges the courts to try to hold the scales evenly between freedom of the press on the one hand and abuse of that freedom on the other.

The final chapter draws together most of the themes discussed under the title “Eternal vigilance”. In this he discusses with vivid illustrations and examples the abuse, misuse, and accompanying injustices of the freedom of contract, freedom of association, freedom from injury and freedom of religion, and regrets that lawyers have always not heeded as they should, the words of their brother J.P. Curran that “the price of freedom is eternal vigilance” but instead have stood by, whilst wrongs have been done without protest.

First among these is the myth now, or abuse of the sacred principle of freedom of contract by the increasing use of standard form contracts, exemption clauses, and conditions by big businesses and the consequent injustices to the powerless individual. He discusses the efforts made in piecemealfashion to remedy this state of affairs and what judges have done to mitigate the situation within the limits set by accepted doctrines, the private legislation of companies to overcome the decisions of the courts and the inability of the courts to extend their rules to invalidate some of these as that would involve them too much in questions of public policy which is said to be an “unruly horse to ride”. However, he recommends the test of reasonableness as a remedy to deal with this vexed question because, although parliament would he much better to deal with the conflict, if it doesn’t, the courts should.

Second, although freedom of association is a bulwark of democracy, present-day trade-union practices – the “closed shop”, the right to strike – have made it the antithesis of what it stands for, the curtailment of the individual’s right to work and the infliction of hardships, inconvenience and injury, without redress, on innocent individuals. Similarly, on the employers’ side, freedom of association has also led to injustices to the public whom they should serve: stop lists among monopolies, price rings at auction and tenders to name just two.

Third, on the basis of freedom from injury, the old rule based on the notion of fault is out of date in a mechanical or atomic age and many injustices arise from its continuation: an injured person may fail to get compensation simply through want of evidence that the other was in fault. With the advent of present day scientific processes and atomic energy, Sir Alfred submits that there should be absolute liability in all cases whenever the defendant can be protected by insurance. Besides the injustice to the injured due to the difficulty of proving fault, there is also an injustice to the defendant which may arise from the necessity of finding fault. This means that so long as compensation is dependent upon proof of fault, injustice will continue. Sir Alfred, therefore concerned with the road to justice, submits the adoption of a new test – not “whose fault was it?” but “on whom should the risk fall?” which, whilst still recognising negligence would leave the moral duty to take care be enforced in other ways than by refusing compensation to the injured.

Lastly, Sir Alfred discusses the infringement of the freedom of religion by churches and taking of the vexed question of marriage between two parties of different denominations and the problem it raises as to in which denomination are the children to be brought, he condemns as illegal any attempt by any Church to impose conditions or demand promises that such children will be brought up in its beliefs or whatever.

In conclusion, Sir Alfred calls on all judges and lawyers to realise that the sovereign remedy for all ills is, not only an Act of Parliament because parliament has not got the time nor the capacity to guard all the points at which freedom is threatened and therefore it is for us, each and everyone of us, to be vigilant at all times for “this is the condition upon which God hath given liberty to man”.

Sir Alfred’s conclusion is not one of despair for the future of the subject matter of his book, for it is not only the function of legislatures to be the only fountain of justice but the courts of justice and the judges and advocates of justice. The real merit of “ The Road to Justice “is both in the depth with which the material is covered as well as in its thought illuminating effect and the way in which the author covers a mass of detail without becoming dull or pedantic. It defines, discusses and criticises with submissions for improvement, the use, misuse and abuse of the basic principles and pillars of law and justice, the importance of morality in the administration of justice and the role and responsibility that is lacking in and should underlie the quality of the just administration of justice.”

The Road to Justice” is the road to justice; it is a lawyer’s bible, a wise book, a book of wisdom by an eminent judge on a vital subject underlying the whole superstructure of the law arid of society that must be read by everyone who is interested to know about the fundamentals of the quest for justice. In it are vividly illustrated, with historical and modern instances, the essence of the age-old effort of the Common Law to do justice, along with a wealth of interesting allusions and incidents that make-it fascinating reading and with considerable profit.

Lord Justice Sir Alfred Denning, as he then was, and the author of the book, “The Road to Justice” was the hero of law students and young lawyers in the early 1950s and 1960s. I first heard the name at University where Professor Ellinger told us about this extra ordinary judge, with his passion for justice.

Years later, when I, too became a lawyer, I wondered what had driven him, what had made the man. It is of more than passing interest to know what kind of men and women judge us, since their power to affect our lives is awesome. It is also rewarding to view them against the social background and preoccupation of their age.

Alfred Thompson Denning was born in January 1899. He was educated at Andover Grammer School and Magdalen College, Oxford. A brilliant student, he was placed in the 1st Class in both the Mathematical Final School and subsequently the Final School of Jurisprudence, i.e. he had a Double First Class Honours in Mathematics and Jurisprudence. Eldon Scholar and Prize Student of The Inns of Court he was Called to the Bar in 1923, becoming a King’s Counsel (KC) fifteen years later. In 1944 he was knighted and appointed a Judge of the High Court of Justice. He became a Lord Justice of Appeal and a Privy Councillor in 1948. Created a Life Peer in 1957 he took the title Baron Denning of Whitchurch. The same year he was appointed a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary and was Master of the Rolls from 1962 to 1982 – some 20 years and longer than any other Master of Rolls either before or after him.

Lord Denning’s life practically spanned the twentieth century. His cases cover most of the interests and activities of its second half. Often innovative, frequently controversial, few would disagree that he was the greatest and most colourful judge this last century has known. From his appointment as a Judge of the High Court in 1944 to his retirement in 1982 from the position of Master of the Rolls, Lord Denning’s decisions and thinking have had and will continue to have, a profound effect on the development of English Law, not only in England but also throughout the English speaking world: His reputation also extends far beyond England and beyond the legal profession.

Lord Denning’s highly individual approach to the law and his view of its function, what it is and should be, in our society; his own stated ideals on curbing the abuse of power, on morality, and respect for the democratic process; his stress on the importance of justice, at the expense, if necessary, of the rules of law and how judicial law-making can be reconciled with the assumptions of parliamentary sovereignty, and his unique power and views in any debate on judicial, legislative, and executive decision – making in the state need to, and should always be, taken seriously.

He saw his judicial roll as the making of law, not merely the interpretation of it, and gave judgments which place the judiciary at the centre of political and social change. Naturally conservative he still liberalised social policy and stood up consistently for individual rights. A firm believer in Christian marriage, he nevertheless eased divorce procedures and brought about the protection of women’s property rights.

From the time he became a judge at 45, the youngest on the Bench, his independence of mind, passion for justice, wry humour, crisp staccato style and considerable flair for publicity brought him into a position occupied by only a few judges in the past – as one who spoke for the nation.

Writing in The Times of 5 January 1977, Lord Justice Sir Leslie Scarman, as he then was, and another illustrious English Judge said; “The past 25 years will not be forgotten in our legal history. They are the age of legal aid, law reform and Lord Denning”. The “Road to Justice” is one of 13 Books, 6 Judicial Inquiry Commission Reports, 19 Law Journal Articles, 25 Lectures and 10 Book Reviews totalling 73 publications and all masterpieces by Lord Denning, Master of the Rolls, and the Master who knows, before and after retirement in a most illustrious life of 100 years. I believe that the next 100 years will continue to be a century of continuing law reform, continuing legal education and Lord Denning! Is there anyone in this august gathering who disagrees? There is none.

My Lord Chief Justice

Director General,

Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen,

Fellow Students,

It now only remains for me to conclude with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. of the United States Supreme Court when he wrote: “The reason why people pay lawyers to argue for them is that in societies like ours the command of the public force is entrusted to the judges in certain cases, and the whole power of the state will be put forth, if necessary, to carry out their judgements and decrees.”

Justice Holmes’ reasoning provided eloquent rationale for the publication of Honourable Chief Justice Edward F. Hennessey’s reflections called “Excellent Judges and Lawyers” in which he concludes: “May judges and lawyers never lose the sense of awe at the power they exert and at the importance of every decision. In some aspects the legal or judicial officer, of all public officials, exerts the ultimate power in the community. I suggest, in considering the three branches of government that a loss of public confidence in the Judiciary including the Bar, is most likely to cause the people to despair. The judge or lawyer who appreciates this is the judge or lawyer who will be dedicated to excellence and, in presiding or conducting, is most likely to achieve: integrity, wisdom, impartiality, even-handedness, courage, courtesy, patience, compassion, modesty, diligence, efficiency, decisiveness, dignity, with humour, humour, with dignity, collegiality, legality, legal knowledge and JUSTICE.

We must therefore pray the Lawyers’ Prayer by the distinguished American Attorney, Louis Nizer, when he wrote in his latest book, “Catspaw”;

Please, O God, give us good health with which to withstand the rigours of a most arduous profession – the law.

Please grant us equanimity which calms everyone around us and enable us to balance like a gyroscope in the storms of contest.

Give us peaceful sleep, for while we must keep our mind on our work, we must not keep our work on our minds.

Touch our words with eloquence, not in the sense of harangue, but in the true meaning of oratory-a flashing eye under a philosopher’s brow.

Diminish our worries, particularly those anticipated worries which are like interest paid on a debt that never comes due.

Increase our capacity for work, so that we will not suffer the fatigue of thought and will plough deep while sluggards sleep.

Please see to it that we never become afraid of the violence of an original idea or of a stretched mind.

Above all, O Lord, do not diminish our intensity for a client’s cause, for from it spring the flames which leap over the jury box and set fire to the convictions of the jurors.

We would pray that our efforts do not blind us to the uniqueness of love, the comfort of friendships, and the joys of a cultivated mind.

Please teach us horizontal as well as vertical faith-vertical in obeisance to you, horizontal in our obligations to the community.

We cannot control the length of our lives, but we can control the width and depth of our lives. And we know that when you finally touch us with your fingers to permanent sleep and examines us, you will look not for medals or honourary degrees, but for scars suffered to make the world a little better place to live in.

We thank you for casting us in the legal profession, dedicated to justice, imbued with the sanctity of reason.

The law has honoured us. And we shall always honour the law.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I thank you all.