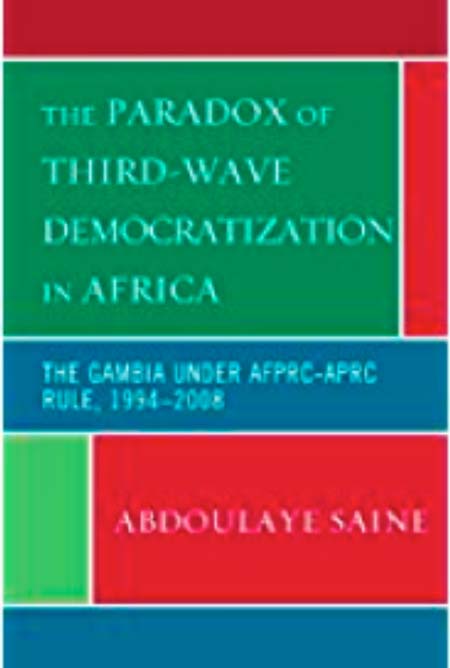

The

Gambia under AFPRC-APRC Rule, 1994-2008, Abdoulaye Saine, Lexington Books,

2010.

Professor

Saine has been in the forefront of the fight to end the 22 years of tyranny

under Yahya Jammeh, as head of many pro-democracy groups based in the USA.

What

he has done equally well also was to write consistently on the assault by

Jammeh on Gambian democratic values since 1994 in a series of journal articles

and now in this excellent book whose full title is ‘The Paradox of Third-Wave

Democratization in Africa’. It has to be said that this is not a popular work;

it is highly academic and so the ordinary reader may find it rather heavy with

information and analyses; yet, it is the most comprehensive and updated work on

the Jammeh era.

The

book is divided into 10 chapters. The first two chapters lay out the

theoretical framework for the work. In chapter three onwards, the author

masterfully dissects the junta rule of 1994-1996, the so-called Transition to

civilian rule, (p.230). But before doing so, the author gives a thorough

background of the last years of the ousted Jawara regime. He was quick to

conclude that although Jawara was a benign and measured leader who ‘crafted and

personally presided over a moderate foreign policy’, his regime had

shortcomings.

The

military coup of July 1994 latched onto these shortcomings to justify itself.

Here even a respected scholar as Saine did not wink in calling the coup as

‘bloodless’ (p.1) even though we all now know that the bloodletting was only

kept in abeyance; in the coming months and years, our country was to be stained

in blood as the Jammeh infernal machine worked overtime against perceived and

intending enemies such as human rights activists, journalist, political

leaders, and ordinary people.

Ironically,

even the security forces were not spared the tyrant’ whip :an issues well

discussed on page 82 where Professor Saine gives a heart wrenching account of

the harsh violations of the rights of people in uniform under Jammer’s rule. It

seems the guillotine’s blade was now re-oriented towards chopping off the necks

of the perpetrators of the 1994 coup. The so-called revolution was eating its

own makers. This according to the author was the apotheosis of the tyranny.

Further

into chapter six, the author reveals that under Jammeh the Gambia was a most

corrupt society, p.91. Therefore, already the regime which came to power under

the banner of transparency and probity was now mired in corruption from top to

bottom.

On

page 127, the learned author asks a rhetorical question worth asking: ‘has The

Gambia moved closer to ‘democracy’ after three presidential elections’, he

answered no! Indeed, he reveals that under Jammeh, elections were mere rituals

to hold each lustrum to have a veneer of legitimacy and nothing else. The

despot never believed in elections as democratic procedures, but he knew he

needed to be seen to be holding them as a way to distract.

The

last chapter is indeed worth reading thrice over. Here he suggest ways forward

in a post-Jammeh era. He suggests a Truth Commission and or a National

Conference to settle our bleeding wounds. When he wrote these ideas, no one saw

Jammer’s fall from power so soon and therefore, Saine’s postulations are worth

reading especially by our policy makers to ensure a smooth entry into the Third

Republic.

Available

at Timbooktoo: tel:4494345