Some

months ago, in a ditch beside one of the main streets of Bunia, a dusty,

war-battered city in northeastern Congo, I noticed a small, broken-down, dull

green armoured car, the gun barrel in its turret tilted awkwardly toward the

sky. Removing war debris can be an expensive luxury in a poor country, and the

wreck seemed an apt symbol of the indelible mark that 15 years of intermittent

conflict has put on this nation.

The

fighting has left tens or even hundreds of thousands of women gang-raped and

led to what may be millions of war--related deaths; at its peak, some 3.4

million Congolese (the only one of these tolls we can be remotely sure of) were

forced to flee their homes for months or years. But it draws little attention

in the United States. As Jason K. Stearns, who has worked for the United

Nations in Congo, points out, a study showed that in 2006 even this newspaper

gave four times as much coverage to Darfur, although Congolese have died in far

greater numbers.

One

reason we shy away is the conflict’s stunning complexity. “How,” Stearns asks,

“do you cover a war that involves at least 20 different rebel groups and the

armies of nine countries, yet does not seem to have a clear cause or

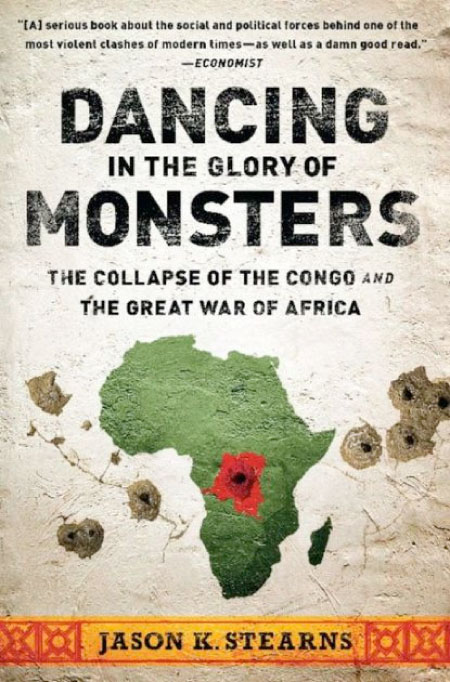

objective?” “Dancing in the Glory of Monsters” is the best account so far: more

serious than several recent macho-war-correspondent travelogues, and more lucid

and accessible than its nearest competitor, Gérard Prunier’s dense and

overwhelming “Africa’s World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the

Making of a Continental Catastrophe.”

A

fatal combination long primed this vast country for bloodshed. It is wildly

rich in gold, diamonds, coltan, uranium, timber, tin and more. At the same

time, after 32 years of being stripped bare by the American-backed dictator

Mobutu Sese Seko, it became the largest territory on earth with essentially no

functioning -government.

Then

it was as if waves of gasoline were poured onto the tinder. When the Hutu

regime that had just carried out the genocide of Rwanda’s Tutsis was overthrown

in 1994, well over a million Hutu fled into eastern Congo, then known as Zaire.

These included both the génocidaires and their defeated army (the

abandoned armoured car in Bunia was theirs) as well as hundreds of thousands of

Hutu who had not killed anyone but who feared reprisals at the hands of the

Tutsis now running Rwanda.

In

their militarized refugee camps, the génocidaires rearmed and began

staging raids on Rwanda. To try to put a stop to this and install a friendly

regime in the huge country next door, Rwanda, along with Congolese rebel

allies, invaded its neighbour in 1996 in what is known as the “first war.”

Mobutu’s kleptocracy in Kinshasa rapidly crumbled; the dictator fled overseas

and died a few months later. Laurent Kabila, a portly veteran of some years as

a rebel in the bush and many more as a shady businessman in exile, now found

himself leader of a Congo where almost all public services had collapsed. He

was not the man to fix them. Stearns gives a vivid anecdotal picture of Kabila

as someone far out of his depth, trying to run a government by literally

turning his house into the treasury, with thick wads of bills stashed in a

toilet -cubicle.

Kabila

soon parted ways with his Rwandan backers. Then came the “second war”: an

invasion by Rwanda and its ally Uganda in 1998. They failed to overthrow

Kabila, however, because, dangling political favours and lucrative business

deals, he enlisted military help from several other countries, principally

Angola and Zimbabwe. A few years later he was assassinated and succeeded by his

son Joseph. Eventually, a series of shaky peace deals ended much of the

fighting.

But,

as Stearns says, “like layers of an onion, the Congo war contains wars within

wars.” For example, Uganda and Rwanda fell out badly with each other and fought

on Congo soil. Each country then backed rival sets of brutal Congolese warlords

who sprang up in the country’s lawless, mineral-rich east. And when Rwanda’s

Hutu-Tutsi conflict spilled over the border, it fatally inflamed complex,

longstanding tensions between Congolese Tutsis and other ethnic groups. This is

merely the beginning of the list.

The

task facing anyone who tries to tell this whole story is formidable, but Stearns

by and large rises to it. He has lived in the country, and has done a raft of

interviews with people who witnessed what happened before he got there.

Occasionally the chain of names of people and places temporarily swamps the

reader, but on the whole his picture is clear, made painfully real by a series

of close-up portraits.

In

one crowded refugee camp there were no menstrual pads; women could use only

rags that, repeatedly washed out, left rivulets between the tents streaked with

blood, as if a reminder of the carnage they were fleeing. Or here is a Rwandan

Army officer from a death squad that took revenge on Hutu refugees, including

women and children, telling Stearns: “We could do over a hundred a day.... We

used ropes. It was the fastest way and we didn’t spill blood. Two of us would

place a guy on the ground, wrap a rope around his neck once, then pull hard.”

Congo’s

history is interwoven with all of its neighbors, but none more closely than

Rwanda, whose government in the 1990s understandably feared that

Congo-based génocidaires could continue to rampage over the border

and slaughter more Tutsi. But the genocide in no way excuses subsequent Rwandan

massacres of tens of thousands of Hutu in Congo. Nor the way Rwanda quickly

became the latest in the long string of outsiders — from Atlantic slave traders

to Belgian colonizers to mining multinationals — who have so plundered this

territory.

Stearns

is somewhat easier on Rwanda here than he has been elsewhere, for example, in a

United Nations report he contributed to. But he does quote the Rwandan

strongman and current president Paul Kagame as calling his military

intervention “self-sustaining,” and cites an estimate that the Rwandan Army and

allied businesses reaped some $250 million in Congolese minerals profits at the

height of the second war. Such figures are backed up in abundant detail in a

series of United Nations reports, and ultimately led Sweden and the Netherlands

to suspend aid to Rwanda.

Not

so the United States. It has supported Kagame for years, contributing

indirectly to Congo’s suffering. How this media-savvy autocrat has managed to

convince so many American journalists, diplomats and political leaders that he

is a great statesman is worth a book in itself.

No

account of Congo can yet have a happy ending. Although Stearns dutifully makes

some policy proposals — more carefully directed aid with conditions on it; more

stringent regulation of “mining cowboys”; a mechanism for holding the worst

perpetrators to account — he is wise enough to know how difficult it will be to

halt 15 years of violence and pillage. Indeed, the price of recent peace deals

has been the incorporation of a number of rapacious warlords and their troops

into the ill--disciplined Congolese national army.

That

wrecked armoured car by the roadside in Bunia? It’s still there. A friend sent

me a cell phone photo the other day. Only now, like a trophy, it has been

lifted up onto a concrete pedestal, which is painted with the name of a nearby

army unit.

Available

at Timbooktoo Tel:4494345