The

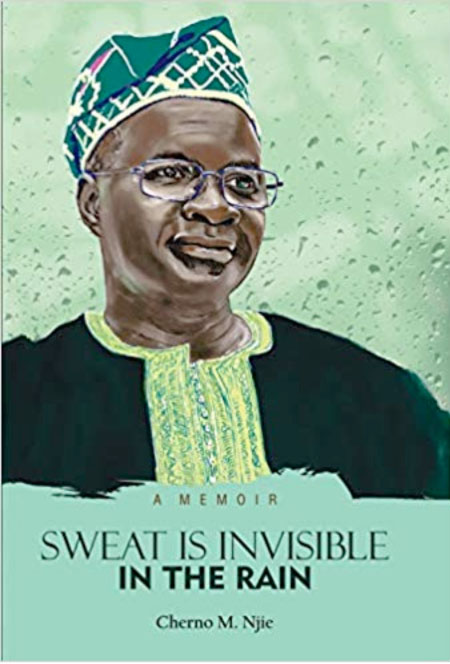

book, Sweat is Invisible in the Rain, written by Cherno M. Njie and published

by the Pan-African University Press, is better classified as a documentation of

three interconnected stages of the author’s life, career, vision, and ambition.

Such is the importance of the book that a major conference is being convened on

it in Gambia on December 14th, 2019. I am glad to be associated with the book,

proud to occupy a line or two in the contents, and humbled to be associated

with the author.

The

book successfully privileges the historical and the factual over the literary.

It deals with causation using a wide range of facts, explaining why events and

actions occurred at particular moments in time. The principal figures and

protagonists are revealed in ways that reflect their time, age and day. Sweat

is Invisible in the Rain will surely asserts itself as a book to read and be

reckoned with, as it captures the commonalities of personal experiences in The

Gambia, the shortcomings of the country’s political elite, the intriguing

nature of dictatorship, and a wide range of dialogue on the degeneracy of

political institutions. The antipathy that the leadership of the country

aroused is captured with brilliance, as well as the responses to how to deal

with unpopular power. I admire Njie’s voice and courage as he narrates the

sickness of leadership, the weakness of followership, the limitations of state

power, and the repetitiveness of calamitous history.

The

book starts from Njie’s growing up in a relatively unknown and small African

country, The Gambia (the first stage), to his transition to perhaps one of the

most popular migrant destination countries in the globe, the United States of

America (the second stage). The third stage takes center stage of the events

captured in the book as it details how the two previous life’s stages induced

the author to embark on a series of moves that set in motion the process of

acting as a change agent. Consequently, his first stage of existence during his

childhood in The Gambia keys into the immense benefits that he experienced in

his second stage of existence, The United States of America.

The

title of the book aptly encapsulates all that the author went through, which

were not noticeable when they were occurring, but which cannot be swept under

the carpet simply because of their non-noticeability, disguise and secrecy.

Sweat is surely invisible in the rain, but the laborer who worked hard in the

rain knows that the rain just served as a camouflage to hide the sweat

generated from his labor. And when rain falls, it can create its own problems,

with the rain and sweat inducing unnoticeable pains and anguish.

Cherno

Njie is able to map out in detail his personal travails, albeit in consonance

with those of some others as they, over a period of more than a decade,

embarked on missions, as well as developing various strategies to achieve an

objective whose benefits are not personal in any way, but rather collective to

a large, unsuspecting and ignorant populace. The sweat of the author and ‘his

band of merry men’ might have gone invisible in the myriad of raindrops of

events that happened in The Gambia between 1996 and 2016. However, with the

expediency with which this book was written and the fact that the story was

told by someone who played a significant part in the many facets of the plot,

Njie succeeds in bringing to the fore, the invisible sweat that seems to have

been lost in the rain with respect to the journey to free an African people

from the reigns of tyranny.

Before

going into the chapter-by-chapter review, a glance at the acknowledgments given

in the book introduces the reader to the individuals who were instrumental in

the course of documenting the stories as well as the major players in the

events who took center stage in the book. All these are carefully outlined and

perfectly detailed within the confines of the acknowledgment page. The preface

introduces the reader to the central event of the book: the failed coup attempt

which involved the author and a handful of other patriots in the small West

African nation, The Gambia. As with any proper preface, it gives a brief

account of the reasons for the coup attempt as well as the aftermath of it, which

saw some of the perpetrators killed, some captured, while some fortunately

escaped but eventually made to pay for their actions on a foreign soil. The

last set of the most fortunate who did not die includes the author. An attempt

is also made in the following section to open the reader’s mind to the history

of The Gambia, an effective step to equip the reader with some historical

antecedents of the Gambian people concerning politics, governance, and

leadership. This section traces Gambian history to centuries back. Also, credit

should be given to the author for taking time to prepare the mind of the reader

in advance to similarities of persons’ names who may or may not be related, but

which is just a common occurrence among the Senegambian people. Without this,

the reader would have been a bit lost in the maze of seemingly related

nomenclatures of people who share no familial relationship.

The

first chapter, as the title implies, ‘Close Quarters: Growing Up in Banjul’,

details the city of Banjul where the author grew up, a careful comparison

between the Banjul of old times and the one left behind by the evident

antagonist of the book plot, Yahya Jammeh, the erstwhile dictator of The

Gambia. Njie affirms that nothing seems to have changed in the 22 years of Yahya

Jammeh’s rule, a common characteristic of most dictatorship governments in

Africa. So that both the African and non-African reader can immerse themselves

into the cultural settings of the first stage of the book’s plot, the author

does justice to highlighting the various family settings that is ubiquitous in

the capital of The Gambia; Christian homes having distinct attributes to Muslim

homes with respect to composition and way of living.

The

chapter also highlights the components of the Wolof caste system. Among the

experiences of growing up in African communal settings is the issue of

circumcision, which is also embedded in the book. Brought to the fore in this chapter is the

disposition of Africans to hold on perpetually to superstitious beliefs, including

beliefs in the existence of flesh-eating witches who are ultimately made to

confess their sins, casting of spells, laying spiritual curses and the

manifestation of evil spirits. For a book that details life in Africa, the

absence of such a subplot would have led to the absence of a very pertinent

aspect of African thought and mentality. Upholding some of these beliefs might

be rational; however, as the book notes, there are times when these beliefs

place more damage than good to the African people as became evident under the

oppressive rule of Jammeh who exploited these beliefs to the people’s

detriment. These beliefs, as the author notes, are in sharp contrast with the

second stage of the book’s plot setting, the USA, a nation that is built on the

ideology of secularism and scientific methods.

The

second chapter sets the tone for the author’s transition from a small unpopular

African nation to a massive and popular country far away in another continent,

deep into Texas in furtherance of his formal education, which, as pointed out,

was quite different in approach to what he was familiar with growing up in The

Gambia. Affirming the frenzy that envelopes Africans moving to the western

world for the first time, the book rightly captures the drama that goes with

leaving one’s family in Africa for greener pastures, education inclusive. This

practice has always been the norm for affluent families in Africa, as they held

the belief that better and qualitative education abroad is a sure way to wealth

and riches. This is not entirely a falsehood as later events in the book prove

this assertion to be right. Settling down in a new country is not always going

to be so easy, and the same was rightly captured by the author. True to the

assertions, it took little effort for the migrant to afford a car, something

that would have been close to impossible in an African student setting.

In

Chapter three, ‘The Jammeh Years: 1994 – 2016’, the story quickly moves to the

central plot of the book wherein Njie brings to the reader’s awareness the

introduction of the antagonist by telling the story of how Jammeh came to

power. As with every good book, it is always necessary to accord the antagonist

a grand entry into the plot, more so in a story that revolves around military

rulership, dictatorial tendencies and ultimately the subplot of military coups.

The author, within the context of the book, exposed the reader to the events

that necessitated the grand entrance of the major antagonist of the book,

Jammeh. Years of misrule by the first president of The Gambia, Dawda Jawara

(who passed away on August 27, 2019), served as an impetus for the emergence of

Jammeh as the new head of the Gambian government, even though he rose to the

exalted position illegitimately.

Another

theme of the book which looks hidden in the shadow of the overall military

theme is the propensity of powerful countries like the USA to follow up on the

various happenings around the globe with respect to governments and regime

change. The USA has been known as a nation that engages in intelligence

gathering in virtually all countries in the world, and this makes the US

government a prospective conspirator to acts that leads to political

instability in other relatively smaller and weaker nations.

The

plots in the book are interwoven, and they do not follow a definite order, as

it is necessary to weave the story in a manner that will enable the reader to

understand the expediency of events, actions and motivation that create a back

and forth sequence of storytelling. Sweat is Invisible in the Rain allows the

work to represent its author, and to speak to a tumultuous moment in the

history of The Gambia. The book offers the fullest story of Njie’s life, in

addition to a remarkable understanding of his mother country in both its

volatile and remarkable moments. This highly readable and valuable memoir is

one of the best to come out of West Africa. I admire his ability to tell the

story so well and clearly. I can only hope that the people of The Gambia will

get the justice they seek and deserve, and the progress that they dream about.

With the humiliating fall of Jammeh, one can proclaim, as it was done centuries

ago in another clime and era:

“How

the mighty have fallen, and the weapons of war perished!”. Holy Bible, 2 Samuel

1: 27.

Available

at Timbooktoo tel 4494345

Read Other Articles In Article (Archive)