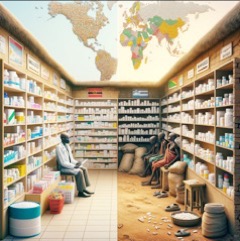

When it comes to quality products that minimize the risk of exposure, Western countries sit atop the food chain. Despite recent trends in outsourcing manufacturing to Asia, particularly in the pharmaceutical sector, these nations typically hoard enough of the finished generic medications that millions of dollars worth of drugs lose their shelf life before consumption. This is the true story of the haves and the have-nots.

These nations are often categorized by the presence of a Stringent Regulatory Authority (SRA). An SRA is a national drug regulation authority that the World Health Organization (WHO) considers to apply stringent standards for quality, safety, and efficacy in its process of regulatory review of drugs and vaccines for marketing authorization. The concept of an SRA was developed by the WHO Secretariat and The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria to guide decisions regarding the procurement of medicines for humanitarian assistance. The idea is that countries with non-SRA drug authorities can use accelerated processes to facilitate approval (registration or marketing authorization) of medicines, including vaccines and biologics, which have already been approved by SRAs.

As of 2022, the national regulatory authorities of 36 countries are considered SRAs. These countries include Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and United States of America.

Notably, no African country is listed as having an SRA. The regulations of medications from these nations have slowly evolved from a practice of safeguarding the public to potentially inflicting harm to protect archaic systems of regulation, often influenced by market authorization and share rather than continuous pharmacovigilance and increased density of quality medication.

It is crucial to emphasize that sourcing is everything when it comes to medications that are safe and effective. Nations with SRAs realized early on that the tightest regulations happen at the site of manufacturing, where institutions like the FDA add additional layers of certification and tracking before offshore manufacturers can even access their markets. It should be a rule of thumb that if a manufacturer is producing goods that do not pass the smell test in SRA countries, the African market should also be closed off to them.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime estimates that nearly half a million people in sub-Saharan Africa fall victim to counterfeit medicines each year. The 2023 report ‘Trafficking in Medical Products in the Sahel’ indicates that 19-50% of medical products in the region are falsified or substandard. Between 2017 and 2021, over 605 tons of questionable medical products were seized in West Africa alone. Africa accounts for an astounding 40-50% of the world’s substandard medications, with an estimated 1 in 2 drugs failing to meet quality control standards upheld in Western countries.

Counterfeit drugs pose two primary dangers: they may contain little to none of the active ingredient, rendering them ineffective, or they may include harmful inactive ingredients, such as anti-freeze. Manufacturers of these substandard products intentionally exploit nations with a high amount of poor and inadequately educated citizens, weak regulatory environments, and insufficient laboratory infrastructure for quality control.

Like many sub-Saharan countries, Gambia is yet to activate its local drug manufacturing prowess and imports 100% of its medications, further necessitating an environment conducive for quality distributors to feed our local supply chain. While Africa has a unique opportunity to increase its manufacturing prowess through industry innovation accompanied by more agile and progressive regulation, it is crucial to assess how overregulation is directly impacting the health of Africans, especially in countries that heavily rely on imported medications. Overregulation can create barriers for quality distributors, limit access to safe and effective medications, increase the risk of substandard and falsified drugs, lead to higher costs for patients, stifle innovation, and strain healthcare systems. The following are some of the negative consequences:

1. Limited Market Attention

In SRA nations, physicians have the luxury of prescribing medications based on what offers the best chance at therapeutic success for their patients. They have access to a wide range of drugs, including specialty medications such as cancer drugs, which allows them to tailor treatment plans to individual patient needs. This personalized approach to medicine is made possible by the availability of a diverse array of medications that have undergone rigorous testing and approval processes.

In contrast, in sub-Saharan Africa, what may appear to be a cookie-cutter approach to prescribing medication is often a result of the limited variety of medications available, particularly when it comes to specialty drugs. This scarcity is largely due to the limited market attention that countries like Gambia receive from manufacturers approved to produce products for SRA nations.

Gambia’s extremely small market size means that it cannot command the attention of these manufacturers, who are more likely to focus on larger, more profitable markets. As a result, Gambia and other sub-Saharan African countries are often left with limited access to the high-quality, specialty medications that are readily available in SRA nations.

While some importers of SRA-certified medications may use a marketplace distribution model that allows them to access quality medication and redistribute it to sub-Saharan Africa, this process is often harder and significantly more expensive than sourcing medications from third-tier manufacturers in Asia. These manufacturers may have a higher chance of distributing substandard medication, which can lead to increased hospitalizations and early death, especially for patients with chronic conditions who require consistent access to high-quality medications.

The limited market attention that sub-Saharan African countries receive from SRA-approved manufacturers creates a vicious cycle. The lack of access to quality, specialty medications leads to poorer health outcomes, which in turn reduces the demand for these medications and further disincentivizes manufacturers from entering these markets. This cycle perpetuates the disparities in healthcare access and outcomes between SRA nations and sub-Saharan Africa.

2. High Administrative Fees

When provisions are made for medications from EU and USA to enter markets in sub-Saharan Africa, the process is often hindered by exorbitantly high and arbitrary administrative fees. These fees, which are imposed by local regulatory authorities, create a significant barrier for importers who wish to bring in a wide range of medications to address both communicable and noncommunicable diseases.

The high administrative costs associated with importing medications from EU and USA markets serve as a strong disincentive for importers to expand their product offerings. Instead of being able to provide a diverse range of medications that cater to the varying needs of the population, importers are forced to be selective in the products they bring in, focusing on those that are most likely to generate a profit despite the high fees.

In the Gambia, a recent 2023 Private Members Bill aimed to create a pathway for “LISTING” medications sourced from SRA countries. This initiative, intended to incentivize importers to improve the quality of their selection and safeguard the public, can arguably be undermined by exorbitantly high arbitrary administrative fees set by regulators.

The process involves a $25 annual listing fee per product, paid in foreign currency by local businesses earning in Gambian Dalasis. This fee applies to prescription medications, over-the-counter drugs, and devices. It is important to note that this listing applies not only to importers but also to every single place where any medication, over-the-counter cough and cold medications, pain medications, and vitamin supplements are sold, which includes every supermarket in the Gambia. The ability to strictly enforce such a law that covers so many points of distribution is simply impossible under the current constraints.

For importers committed to increasing the variety of SRA-certified medications, the yearly cost can exceed $50,000 for just 2,000 products, regardless of import volume. These high fees create unintended consequences, such as shortages or increased costs passed on to customers, pricing out the majority of citizens for whom cost is the main barrier to quality care. The financial barriers discourage the importation of essential medications, perpetuating health disparities and limiting healthcare providers’ ability to offer the best possible care.

The exorbitant administrative fees imposed on medications from EU and USA markets create a ripple effect that ultimately harms patients and undermines the efforts of clinicians to provide the best possible care. By disincentivizing importers from bringing in a wide range of medications, these fees contribute to shortages, stockouts, and a reliance on external sources of medication that can compromise patient safety and wellbeing.

3. Corruption and Black Market:

Overregulation of medications in sub-Saharan Africa can foster corruption and the growth of black markets. When regulatory bodies impose excessive barriers to the import and distribution of medications, particularly those from EU and USA markets, unscrupulous actors can exploit the system for personal gain.

In many sub-Saharan African nations, regulatory bodies lack the capacity to effectively monitor the movement of medications, leading to weak oversight. This, combined with the high demand for medications in short supply due to overregulation, creates a perfect storm for corruption.

The resulting black market for medications is particularly harmful to vulnerable and underserved rural communities, or “healthcare deserts,” with low densities of physicians and pharmacists. Patients in these areas have limited access to legitimate medications and are more likely to turn to the black market, where medications are often of unknown quality and origin, having not been subjected to rigorous testing and approval processes required by SRAs.

The circulation of unvetted medications in rural communities can lead to severe consequences, such as prolonged illness, suffering, adverse reactions, or even death from counterfeit or substandard medications. Moreover, reliance on black market medications can contribute to the development of drug-resistant strains of infectious diseases, making them more difficult and costly to treat in the future.

In conclusion, the link between progressive regulations and the ability of importers to leverage the quality control mechanisms of SRA nations is undeniable. It is a connection that holds the key to unlocking better health outcomes and, more importantly, restoring and preserving the dignity of every African.

The spirit of medication regulation should not be rooted in defensive strategies aimed at protecting market share or preserving the status quo. Instead, it must be driven by a higher purpose: ensuring that every African, regardless of their socioeconomic status or geographic location, has the fundamental right to access affordable, essential medications that meet the stringent standards set by nations who place the highest value on protecting their citizens.

It is a moral imperative that we recognize the inherent worth and dignity of every African life. No one should be condemned to suffer needlessly or die prematurely simply because they cannot access the medications they need to survive and thrive. The current state of overregulation, corruption, and the proliferation of black markets in sub-Saharan Africa is not just a public health crisis; it is a stain on our collective humanity.

The benefits of such a shift in regulatory approach would be far-reaching and transformative. With improved access to safe, effective, and affordable medications, African healthcare providers would be empowered to make the best possible treatment decisions for their patients, leading to better health outcomes and reduced suffering. Communities that have long been underserved and marginalized would finally have the opportunity to receive the care they need to lead healthy, productive lives.

Moreover, by prioritizing the health and well-being of its citizens over narrow economic interests, African nations can send a powerful message to the world: that every African life has value, and that no one should be left behind in the quest for better health and a brighter future.

In peace, love, and good health,

Dr. IDB.

For more information, follow the work of Dr. Badjie and his Innovarx WOW team on www.igh.gm and on social media @innovarxglobal or call +2866200.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for general understanding and does not constitute a diagnosis. For specific concerns or detailed health advice, always consult your designated healthcare professional.