Reviewed by Jeremy Williams

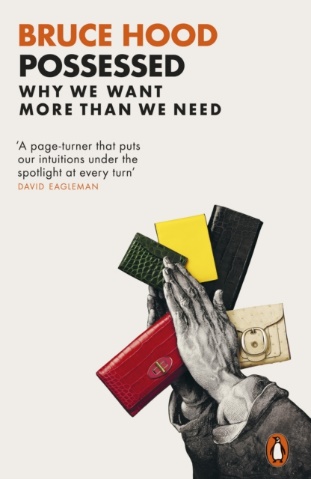

There are plenty of books on consumerism and the social and environmental price we pay for it. Possessed: Why we want more than we need is a little different, because it steps back behind the shopping and consuming, and looks at the idea of ownership itself. What is it? How did it develop? How do we learn to think of some things as ‘ours’? What’s the evolutionary purpose of personal ownership, and does it still serve us?

Ownership is unique to humans. Other animals have territories, and might use objects that they find useful. Only humans value objects in their own right, or use them for status and identity. “The whole of human history is a treasure trove of manufactured possessions” writes Hood, “the oldest of which we now put on display in our museums. We admire the possessions of others.”

Neither has ownership always been important to humans. For 95% of the time that humans have walked the planet, we were gatherers and hunters. You could only own what you could carry, and so many possessions were an encumbrance rather than an advantage. “As we transitioned into agricultural societies, humans began to produce surpluses of resources that could be stored or stolen. This is when ownership became crucially important.”

Today, we use possessions as extensions of ourselves, projecting our power and our identity. We use possessions to cement our place in the world, and draw comfort from them. This starts at an early age, and as a developmental psychologist, the author is particularly good on how children learn to distinguish ownership and form emotional attachments to objects. In the case of my kids, toy bunnies, and you may have had an ‘attachment object’ of your own. As Hood shows, these beloved items can be very useful in investigating the psychology of ownership.

I also liked the way the book draws lessons from how ownership can be contested or negotiated, often using very ordinary scenarios. For example, if you’re bored on a train and you see a magazine on a seat, you will make all kinds of little calculations about who it might belong to, whether it’s left behind or not, and whether you can legitimately pick it up and read it. Another section explores the conundrums over who owns a Banksy when it turns up graffittied on a wall.

As well as the personal and psychological aspects of ownership, the book looks at how ownership shapes society, how it contributes to inequality and creates elites and the establishment. It investigates competition and status anxiety, and sets the problem of consumerism in the context of climate change.

The book isn’t preachy and anti-consumerist, but it does offer some perspective. “Ownership may be in our nature” Hood observes, “but it is not in our best interests.” In particular, we spend too much of our time working to acquire possessions. When we do that, we exchange our most precious resource – time – for something far less satisfying. We should value possessions less and time more, and we’d be better off for it, Hood concludes.

Available at Timbooktoo tel 4494345