In 1444, the citizens of Lagos in southern Portugal witnessed a novel spectacle. As they crowded the beach, some 235 newly arrived Black captives were driven ashore. Overseers dragged families apart as despairing mothers clutched their children and threw themselves on the ground, absorbing the blows raining on their backs. Presiding from horseback over Europe’s first sizable market of sub-Saharan slaves was Portugal’s Prince Henry, known to history as “the Navigator,” and watching nearby was his official biographer, Gomes Eanes de Zurara. Abandoning his usual sycophancy in the face of the captives’ anguish, Zurara bitterly protested that he could not help but “cry piteously over their suffering” and found scant comfort in the thought that their heathen souls, if not their scarred bodies, would be saved.

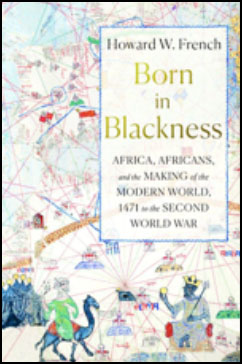

As Howard French painfully establishes, the Portuguese would soon get used to such sights, and the slavers’ unholy swindle — a lifetime of hard labor in return for a shot at the afterlife — would be trundled out across four centuries to justify the shipment of 12.5 million Black bodies to the New World. In “Born in Blackness,” French’s design is not to elicit revulsion — though scenes of enslaved people feeding hellish sugar cane furnaces and slopping manure into dunging holes certainly do that — but to fill an Africa-size hole in conventional accounts of the Age of Discovery and the rise of the West.

In place of Spain and Columbus, French, a former Africa correspondent for The New York Times, proposes Portugal as the true engine of modernity through its deep involvement in sub-Saharan Africa. This may surprise some readers, since Portugal during this period is chiefly remembered for Vasco da Gama’s 1498 voyage around Africa to India. For much of the 15th century, though, Portugal had expended its scant resources on exploring the West African coast. Far from being a giant obstacle standing between Europe and the luxury goods of India and China, Africa had its own allurements, and foremost among them was gold.

Medieval Europeans awoke to the possibility of untold African wealth when reports reached them of an impossibly magnificent expedition mounted by an emperor of Mali. That emperor, Mansa Musa, set out in 1324 on a pilgrimage to Mecca with an entourage 60,000 strong — among them 12,000 slaves — dispensing sacks of gold as he went, including more than 400 pounds to the sultan in Cairo. His trip was the talk of the century, and it lit the imagination of specie-poor Europe. A heavily crowned Mansa Musa was depicted on one 1375 map extending a huge nugget of gold. “This king is the richest and noblest of all these lands,” the legend read, “due to the abundance of gold that is extracted from his lands.” Some said he was the richest king in the history of the world.

French proposes this royal spectacular as the motive force in the creation of the Western world. The prospect of directly tapping African gold by skirting the traders of Islamic North Africa was certainly high on Henry the Navigator’s list. Yet by the time gold was found in quantity (in 1471, the year French takes as the starting date of Africa’s entry into modernity, with the Portuguese fort at Elmina in modern-day Ghana as its key locus), Henry was long dead. Instead, it was slaving that saved his skin, and slaves would soon outstrip gold as the most valuable commodity in Europe’s expanding Atlantic sphere.

To the colonialists, it was all one intoxicating rush of wealth. African laborers, or “black gold,” arduously cultivated sugar cane, or “green gold,” and later cotton, or white gold, all of which transmuted into real gold. Once again, it was the Portuguese who took the lead, modeling Black plantation slavery first on the islands of Madeira and São Tomé, and then on an epic scale in Brazil. If the Spanish found much of the New World and imported the diseases that depopulated it, French argues, the Portuguese discovery in Africa of the means to exploit it surpassed and outlasted Spain’s mining frenzy as a productive economic activity. The Portuguese model was adopted in turn by the Dutch, French and British, who refined it on Barbados into a cruelly efficient system of profiteering that gave owners near total control over their captives’ lives and allowed even murder to go unpunished. The net economic value of plantation slavery has been much debated: French cites compelling research but falls back on his (surely correct) intuition that rival powers would scarcely have spilled so much blood and treasure in their interminable battles to control Black labor if the margins at stake were thin.

“Born in Blackness” is laced with arresting nuggets. It was news to me that the trade of colonial North America was overwhelmingly directed toward the Caribbean, “the boiler room of the North Atlantic economy.” In the late 18th century, white Jamaicans enjoyed an annual income 35 times that of British North Americans. French notes that more slaves were trafficked to Martinique, less than one-quarter the size of Long Island, than to the entire United States, while the French so prized tiny Guadeloupe that they swapped it for the whole of French Canada. The evidence that Africans made the New World economically viable is overwhelming, but in his zeal to press his point, French sometimes goes for broke. He variously traces a more or less straight line from plantation agriculture to the division of labor, productivity metrics, the birth of large corporations, the emergence of commercial credit and capitalism, coffeehouse culture and newspapers, political engagement and pluralism, the English Civil War, the Glorious Revolution, the Industrial Revolution and the Enlightenment.

This is stretching a case well made. “Born in Blackness” is filled with pain, but also with pride: pride at the endurance of oppressed millions, at the many slave uprisings and rebellions culminating in the Haitian revolution, which defeated “the idea of Black slavery itself,” and in the cultural riches of the African diaspora. Some of the most illuminating chapters deal with the nations of Africa themselves: polities such as Benin, Kongo and Mali that featured thriving urban centers, exquisite artisanship and legal and administrative systems on a par with much of medieval Europe. Early on, Portugal discovered the folly of sending soldiers charging up beaches in plate armor and changed tack to making alliances, transacting with informed and eloquent African leaders largely as equals and outsourcing the deadly business of capturing humans for enslavement. Remarkably, no African state would be conquered by Europeans until the 19th century; our modern image of the continent dates from 1885, when the imperial powers divvied it up, creating arbitrary, dysfunctional countries that have stuck. “Africans themselves,” French acerbically notes, “were not consulted.”

French does not shy away from the ruthless complicity of many African leaders in the slave trade, which he blames on the lack of a unifying African identity and a raging thirst for imported silks, palanquins, guns and the rum produced in Brazil by their former brethren. He maps out the shattering cost in depopulation, chaotic regional wars, internal displacement, the erosion of social trust and the unquantifiable legacy that he movingly describes as “the haunting echo of a wound that one carries down through the generations.”

“Born in Blackness” is enlivened with personal anecdotes, but readers looking for a gripping narrative will be disappointed. French repeatedly circles back over his material like a picture restorer revealing a lost world as he calmly insists that we rewrite history. I found the book to be searing, humbling and essential reading.

Available at Timbooktoo tel 4494345