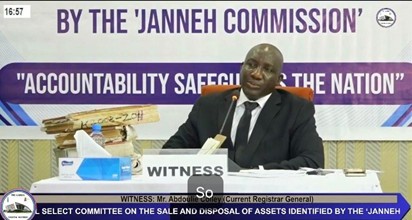

Counsel grilled Colley on why he acted on a mere internal memo from a junior colleague at the Ministry of Justice, instead of waiting for the legally mandated directive from the Director of Lands or a court order.

Colley initially defended his actions, describing them as “just internal” and insisting they had “no legal effect”. But pressed further, he admitted that he wrote “cancelled” next to several properties in the official registry, creating the impression that the titles had been lawfully revoked.

“You knew very well that Mr Taal did not have the authority to instruct you to cancel titles,” counsel reminded him. “Even the Attorney General cannot direct you to cancel title. Why then did you act?” she probed.

Colley replied candidly: “I just did. I acknowledge I should not have acted on the memo.”

The admission stemmed from the government white paper that accepted the Janneh Commission’s recommendations, ordering Jammeh’s vast assets to be forfeited to the state.

Colley, however, admitted that while the white paper had legal force, it was not in itself a directive for cancellation. Only the courts or the Director of Lands could formally authorise the removal of titles.

Colley admitted that even as late as December 2020, many of the properties still legally belonged to the former president and his associates, yet government was already selling them to third parties. “You cannot sell what you don’t own,” counsel stressed.

Colley attempted to justify himself by arguing that references to the white paper in new deeds provided him with sufficient grounds to register fresh assignments. But counsel accused him of “confusing himself and confusing the public”, saying his explanations contradicted basic land law principles.

The Registrar General conceded that his actions created a legal anomaly. “I should not have acted on the memo,” he admitted. “But I did.”

Read Other Articles In Headlines