Tanzania-based UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) will transfer the cases of six out of nine fugitive suspects to Kigali, Rwanda, for trial now that the judges are satisfied that any accused person, who is sent there for trial, will have the benefit of a fair trial.

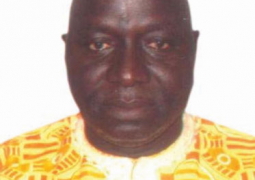

This was announced by the Gambian-born chief prosecutor of the court, Hassan Baboucarr Jallow, in an interview with this paper on Monday.

Hassan Baboucarr Jallow, a former attorney-general and justice minister in The Gambia, said that the tribunal currently has only nine fugitives outstanding.

“We will be filing applications in respect of six of them for their cases to go to Kigali, and I expect the judges, following this recent decision, will also approve those requests,” declared Jallow, who is currently in Banjul on holidays.

Mr. Jallow served as Attorney-General and Minister of Justice in the first Republic of The Gambia, from 1984 to 1994.

He was subsequently elected to the post of chief prosecutor ICTR by the United Nations Security Council in 2003, which was later renewed for another four years.

Mr. Jallow is charged with the responsibility of investigating and prosecuting those persons who committed serious violations of international humanitarian law during the Rwandan genocide in 1994.

“One significant development has been a judgment in granting the request of the prosecutor to transfer a case to Rwanda for trial. It means the judges have agreed that acceptable standards of fair trial exist in Rwanda. They are satisfied that any accused who is sent there for trial will have the benefit of a fair trial,” he said in the interview.

The tribunal started trials of the masterminds of the 1994 genocide -- in which at least 800,000 people were killed within 100 days -- in 1997.

The ICTR was designed to try masterminds of the genocide, while trials against lower-level suspects are taking place in grass-roots courts in Rwanda.

Although it has already extended its work twice, its mandate is now due to expire at the end of 2014.

According to Jallow, the prosecutor will be applying to the judges for the transfer of all the cases of fugitives, except three of them. “This”, he went on, “will of course bring an end to that particular part of our work in terms of searching for the fugitives.”

Jallow also revealed that there has been significant cooperation with regard to the fugitives. “We have been working with countries in the Southern, Central, and Eastern African regions, where most of these fugitives are hiding. We have developed modalities for cooperation with these countries, as well as with regional organizations like the Great Lakes Conference,” he said.

However, he noted that whether or not the court arrests those people now, it means they are now in a position where they can transfer their cases to another country, like Rwanda, so that in the event that they are arrested in future, they can just be taken directly to that country for trial, something he described as “a very significant development”.

“We are actually progressing in terms of finishing our work. We expect that, by the end of this year, the tribunal would have finished the trials of all the detainees, at first instance, and then we will continue with the appeals, which will go on probably till the end of 2012 or early 2013,” he added.

He further stated that, so far, the court has had first instance judgments in respect of some 65 accused persons, and there are more judgments coming up before the end of the year, as well.

He told The Point that the UN Security Council, in a recent resolution, requested that the court try and wind up its work latest by June 2014, expressing hope that the court would have completed well before that date.

“What the council has also decided is to create what it calls a residual mechanism, to carry on the work of the tribunal after 2014, because the nature of the court is such that you cannot completely close it.

“There will be some residual work, that will continue for a while given, for instance, the fact that some of the people who have been sentenced are serving life imprisonments. There may be issues coming up requiring review of their convictions or sentences some 10, 15 or 20 years down the line,” he stated.

Jallow further stated that the court needs to have mechanisms in place, which can respond to and deal with requests from these people for review or revision of their convictions and sentences. “Also we have extensive archives belonging to the tribunal which have to be managed and provide and control access to those archives by accused persons, prosecutors or other interested parties,” he noted.

All these, he went on, require a small core of staff to continue beyond the end of the life of the tribunal itself, for some time.

“In order to deal with that, the council by a resolution created a residual mechanism, which will cover both the Arusha Tribunal as well as the Yugoslavia Tribunal,” he added.

Commenting on the issue of impunity, Jallow said it is absolutely essential that there are mechanisms in place, both at the national and international level, to combat impunity, which means lack of accountability and violation of the rule of law.

This, he said, eventually impacts on peace, progress and respect for human rights.

“It is absolutely necessary, and it can be done. It has been demonstrated that combating impunity is a viable venture, both at the national and international level.

“ The international system cannot deal with all cases, but it has to select the major cases which the national systems may find difficult to cope with,” he said, adding that these cases include those involving people in very senior leadership positions, whom national systems may be unwilling or unable to deal with.

Read Other Articles In Article (Archive)