Raoul

Peck’s documentary brings to life James Baldwin’s urgent ideas about race in

America, and documents a large part of the civil-rights movement.

A

novelist, essayist, playwright, and poet, James Baldwin was a writer with an

arsenal of artistic talent and moral imagination. His signature style was his

prose—startling in its intricate design and depth of perception, and fierce in

its determination to dismantle the racial assumptions of the American republic

and the English language. Baldwin lent his words and energies also to the

civil-rights movement and would write one of the defining books of that era,

The Fire Next Time, his 1963 classic.

While

Baldwin fell out of critical favor in the last decade of his life, and in the

years that followed his death in 1987, his work always remained a source of

deep and demanding insight and beauty—which is why it’s so heartening to

witness the national revival he is currently enjoying. This past September, at

the dedication ceremony of the National Museum of African American History and

Culture, President Barack Obama began his remarks by quoting from Baldwin’s

short story, “Sonny’s Blues.” A group of arts and educational institutions in

New York City declared 2014 “The Year of James Baldwin.” And, over the past

decade, he has received an unprecedented level of scholarly attention,

including the founding of an annual journal committed to reappraising and preserving

his legacy.

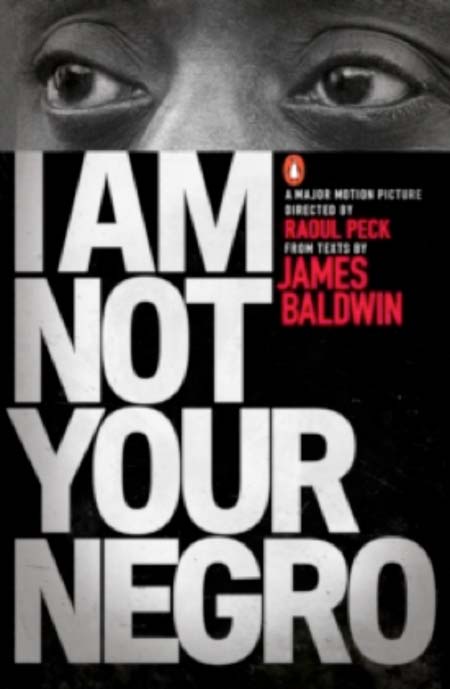

Now

add to this list the director Raoul Peck’s powerful documentary, I Am Not Your

Negro, which received critical acclaim and a Best Documentary Oscar nomination

before it opened nationwide on February 3. The film draws its inspiration from

Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript, Remember This House, intended to be a personal

recollection of his friends, the civil-rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X,

and Martin Luther King, Jr.—all of whom were assassinated within five years of

each other. About a decade after King’s death, in a letter dated June 30, 1979,

Baldwin told his literary agent that he had started sketching out a new book in

which he wanted the lives of these extraordinary men “to bang against and

reveal one another as they did in life.” Baldwin made little progress on the

project, however, and left behind only 30 pages by the time he died in 1987.

I

Am Not Your Negro’s narrative voice comes from this unfinished manuscript, in

addition to Baldwin’s published works and various television appearances.

Unlike conventional documentaries that cede narrative control to family

members, friends, and experts to shed light on the film’s subject, Peck’s film

relies almost exclusively on Baldwin’s writings, read by Samuel L. Jackson.

This ingenious move allows viewers to fully appreciate Baldwin’s unmatched

eloquence and form a portrait of the artist through his own words.

I

Am Not Your Negro begins with the author’s return to the U.S. in 1957 after

living in France for almost a decade—a return prompted by seeing a photograph

of 15-year-old Dorothy Counts and the violent white mob that surrounded her as

she entered and desegregated Harding High School in Charlotte, North Carolina.

After seeing that picture, Baldwin explained, “I could simply no longer sit

around Paris discussing the Algerian and the black American problem. Everybody

was paying their dues, and it was time I went home and paid mine.” I Am Not

Your Negro chronicles Baldwin’s life through the civil-rights movement,

focusing on his personal relationship to Medgar, Malcolm, and Martin.

Repeatedly,

the documentary demonstrates Baldwin’s unique ability to expose the ways

anti-black sentiment constituted not only American social and political life

but also its cultural imagination. Baldwin was an avid moviegoer and wrote

about a number of films in his 1976 book The Devil Finds Work, writings that

are brought to life in the documentary. I Am Not Your Negro uses choice scenes

from various films—Dance, Fools, Dance (1931), Imitation of Life (1934), Guess

Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), among others—to show how Hollywood traffics in

stereotypes of black menace and subservience as foils for white purity and

innocence. In a reflexive move, then, Peck’s film also becomes a commentary on

a U.S. movie industry that was bent on reifying racial stereotypes and on

perpetuating a fiction of America as the greatest purveyor of freedom,

democracy, and happiness.

However

much a documentary about American life in the 1960s, I Am Not Your Negro also

uses Baldwin’s insights to illuminate our own contemporary reality. The movie’s

most gripping scenes intercut footage of police violence directed against black

people in the ’60s and shots of similar violence enacted today, using Baldwin’s

words to collapse the distance between the two eras. The juxtaposition

bracingly highlights the uncanny similarity between the series of black deaths

that punctuated Baldwin’s life during the civil-rights era, and the series of

deaths—of Aiyana Jones, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice,

Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland, and so many others—that mark our own calendar.

I

Am Not Your Negro delivers a remarkable portrait of Baldwin’s life and more

broadly of America’s ongoing racial dilemma. It’s a fitting effect for a film about

a writer who displayed a rare vulnerability in his work, laying bare his own

personal experience as text for national self-reflection. At a minimum, I Am

Not Your Negro introduces viewers who may not have read Baldwin to the genius

of one of America’s greatest writers. How deeply his words resonate today is a

mark of his prophetic vision, which, as the film argues, this nation fails to

heed at its continued peril.

The

book on which this documentary is based is available at Timbooktoo,

T

el: 4494345