All around the world, people waited with bated breath to know this year’s winner of the Mo Ibrahim Prize for excellence in African leadership.

The prize is conceived as an incentive to spur African leaders to commit themselves more and more to improving the economic and social prospects of the African.

In 2007, the Prize Committee of the Mo Foundation had conferred the prestigious award on Joaquim Chissano, former leader of Mozambique. This was followed by Festus Mogae, who ruled Botswana for a while.

The $5m (£3.2m) prize is supposed to be awarded each year to a democratically-elected leader who governed well, raised living standards and then voluntarily left office.

The panel said no candidate had met all of the criteria - as in 2009 and 2010.

Last year, Cape Verde President Pedro Verona Pires won the prize.

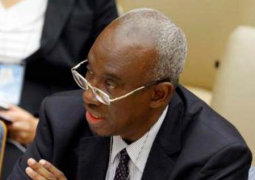

Naturally, it was expected that another African leader would follow in the footsteps of the previous Mo Ibrahim laureates. But committee member Salim Ahmed Salim said on Sunday that “The prize committee reviewed a number of candidates, but none met all of the criteria needed to win the prize.”

Considering the fact that the award is conferred on a democratically-elected former Executive Head of State or Government from a sub-Saharan African country, who has served the constitutionally mandated term and left office in the last three years, it is hardly a surprise that no-one was chosen as winner this year.

The last three years have been years of acrimony across the continent, with the reluctance on the part of Laurent Gbagbo to quit power in Ivory Coast; a vicious cycle of violence in Mali after a military coup there in April; and another coup in Guinea Bissau, among others.

If anyone should have been considered for the award at all, it should have been Rupiah Banda of Zambia. But the Prize Committee knew better.

African leaders should be motivated by this prize to use their executive position to foster good governance and sustainable development for their people.

The prize offers them an opportunity to continue serving humanity on a big scale even after quitting power. It also guarantees personal comfort.

A lucky winner is worth US$5, 000, 000 over ten years and US$200,000 a year for life. A further US$200,000 a year, for ten years, is also available for public interest activities and good causes promoted by the winner.

A true and committed leader should take enough inspiration from such an incentive to drive their country up the development agenda, knowing that their stewardship would not go unrewarded.

Without being presumptuous, the initiator of the award had designed it as a way of curbing greed and selfishness among African leaders when in power.

That no winner was selected this year shows two things.

First, the Prize Committee knows what it is doing. Its members are not out to pander to anyone; clearly, merit is the cornerstone of its operations.

Second, there has been no inspiring leadership on the continent for the past three years. It is therefore a call to action for incumbents to work even harder for the betterment of the African people who they have sworn to serve without fear, favour or ill will.

As the Sudan-born telecoms entrepreneur and initiator of the award, Mo Ibrahim, says, the good governance prize is needed because many leaders of sub-Saharan African countries come from poor backgrounds, and are tempted to hang on to power for fear that poverty awaits them when they leave office.

“Hope is the power of being cheerful in circumstances which we know to be desperate”.

G.K. Chesterton