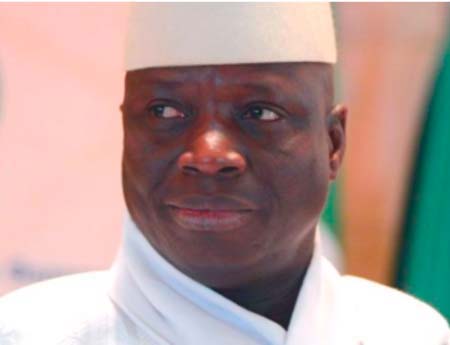

Recovering

the assets allegedly stolen and hidden or invested in foreign countries by

former President Yahya Jammeh could “take many years and numerous processes”,

the World Bank has said.

“Recovering

of stolen assets is a long term process; it could unfortunately take many years

because you have to work through the legal systems of many countries,” the

Country Director of World Bank Louise Cord said on Tuesday as the Bank signs a

US$56 million financing agreement with the government.

The

Gambia government said it will “vigorously pursue” recovery of assets allegedly

stolen by the former president through all available channels, including the

assistance of the World Bank Stolen Assets Recovery unit.

The

World Bank, in partnership with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime,

established Stolen Asset Recovery (StAR) initiative to help developing

countries recover assets stolen by corrupt leaders. Upon request, StAR provides technical

assistance to countries that are engaged in asset recovery cases.

The

World Bank country director said the Bank has received a request from The

Gambia government for support in the recovery of Jammeh’s alleged stolen

assets.

“The

request is being acted upon and a team is involved that is working closely with

the government,” Ms Cord said while reiterating that “the recovery process is

going to take certain amount of time”.

The

total amount of Jammeh’s stolen wealth is not known but preliminary

investigation by the government revealed that just within three years, the

notorious president allegedly embezzled D4.7 billion from state-owned

enterprises, notably Gamtel, Social Security and Housing Finance Corporation,

and the National Water and Electricity Company (NAWEC).

The

new government further accused him of leaving the state coffers with money

enough to pay only two-month salaries of the civil servants.

Jammeh

came to power a pauper but few years into his presidency, he became one of the

richest men on the continent with his net worth said to be more than US$1

billion, according to some estimates.

Recovering

the local assets

In

May, The Gambia government, through a court order, froze 88 bank accounts in

Jammeh’s name or those of his associates, along with 14 companies linked to

him.

For

now, these assets are just frozen, not confiscated.

The

minister of finance and economic affairs, Amadou Sanneh, said: “We need to move to the next stage and that

is going through the court and commission of inquiry which will pass a final

order on these assets.”

He

said the new government is “not going to behave like the former dictator” by

seizing assets and confiscate them with executive directives.

“We

are going through a process that is democratic,” the minister said, while

reiterating the slow pace of recovering stolen funds. “Recovering stolen assets

is a process and it has legal implications and that is why we are going

carefully to recover these assets.”

Economic

experts say the actual investigations that go with asset recovery programmes

can drag on for years because they are complex and costly. Money must often be tracked through countless

offshore bank accounts and shell companies and then directly linked to evidence

of corruption.

Meanwhile,

a report by the World Bank’s Stolen Asset Recovery programme found that, while

nearly $1.4 billion in suspected corrupt assets were frozen in countries of the

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) between 2010 and

2012, less than $150 million was returned.

Many

Africans criticised European financial centres for failing to do more to return

money stolen from the continent by corrupt leaders.