Rome,

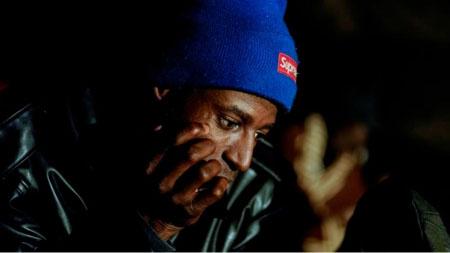

Italy - Before arriving in Italy, Koffi (not his real name), a 29-year-old from

Ivory Coast, did not know much about lasagna.

Training

as a chef with the social cooperative Aiperon introduced him to a brand new

world.

“I

love cooking Italian better than Ivorian food,” Koffi told Al Jazeera.

A

humanitarian residence permit holder, Koffi came to Italy after his family at

home was threatened. He was later abducted in a Libyan detention centre and

then, finally, made a perilous journey across the Mediterranean Sea.

Since

2016, he has lived within the public-funded reception system for refugees in

the southern city of Caserta, north of Naples. He has been provided with an

apartment and studied at a local school.

“We

received a lot - an education and a regular document to stay here. Training

gave me a better hope for the future,” he said.

However,

the enactment of an anti-migrant decree could soon tear all his dreams apart.

Salvini

decree

In

October 2018, former Italian interior minister and far-right League party

leader, Matteo Salvini, drafted the so-called “migration and security decree”.

The

document cracked down on asylum rights by abolishing the “humanitarian

protection” - a residence permit issued for those who do not qualify for

refugee status or subsidiary protection but were deemed as vulnerable.

The

law also excluded people holding international protection and unaccompanied

foreign minors (SIPROIMI), who were entitled to receive further aid and

assistance from the official protection system.

This

means losing their houses and possibly missing out on language classes and

traineeships.

On

December 19, the Italian Ministry of the Interior issued an official

communication compelling these permit holders to leave the reception system by

the end of the year.

A

further letter sought to remove asylum seekers from integration schemes and

transfer them into other reception centres.

“We

had no communication whatsoever before the 19,” Maria Rita Cardillo, the legal

officer of the programme in Caserta, told Al Jazeera.

“All

the projects had previously received an exceptional extension until June, so we

expected a prolongation for the beneficiaries too,” she said. “Moving out those

with of a humanitarian permit in days during the Christmas holidays and with no

foreseen alternative is absurd.”

Caserta

hosts eight holders. Half of them are disabled and have stayed inside the

reception system for between six months and two years.

“Some

would not be able to live outside,” said Cardillo, concerns shared by other

social workers.

Wrong

interpretation

“People

could end up in the streets in the middle of the winter,” said Filippo

Miraglia, who works with ARCI, a network of committees and cooperatives

involved in cultural and social activities, hosting roughly 3,000 refugees in

80 aid and reception schemes.

Miraglia

first sounded the alarm over the consequences of the ministry’s decision, which

he says is based on a mistaken interpretation of the security decree.

“According

to the law, humanitarian protection holders could remain inside the system

until the end of their programme,” Miraglia said. “And the town halls will

renew most of these for another three years.”

After

the official communication went public, the interior ministry on December 21 attempted

to clarify its instructions.

“None

of the 1,428 holders of a humanitarian residence permit who are currently

enrolled in SIPROIMI will end up on the streets,” it said in a statement.

Local

town halls will now decide whether to keep the affected people in the reception

programme.

However,

both Cardillo and Miraglia remain sceptical of this solution, fearing that

bureaucracy will slow down the whole process.

“Even

if there is a new reception programme for humanitarian protection holders in

seven months, what should we do in the meantime?” Cardillo said.

Losing

hope

After

this August’s political crisis of the coalition government, between Salvini’s

far-right League party and the populist Five Star Movement, followed by the

appointment of technician Luciana Lamorgese as the new interior minister,

social and humanitarian workers had hoped for radical change in Italy’s

migration policy.

However,

they are slowly losing hope.

“The

minister of interior wants to avoid an open conflict with the Five Star Movement,”

Miraglia said. “So they are not seeking to overturn Salvini’s policies.”

Tired

of waiting, the coalition of civic society organisation, Table for Asylum, has

called for a demonstration in front of Italian prefectures on December 27.

In

the meantime, Koffi and his fellow humanitarian holders and asylum seekers can

do little more than wait. “What should I do now?” he said, as he reflected on

his future.

Source

Aljazeera