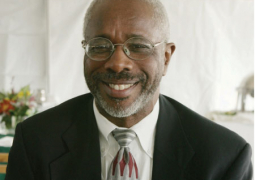

Karamo Bojang, former deputy director of the National Drug Enforcement Agency (NDEA) was yesterday acquitted and discharged by the Banjul Magistrate’ Court presided over by acting Principal Magistrate Dawda Jallow.

He was arraigned before the said court and charged with abuse of offence and stealing, which he denied.

It would be recalled that Karamo Bojang is currently serving jail-term at the Mile 2 Central State Prisons after being convicted by the Banjul High Court for various offences.

Delivering the judgment, the trial magistrate told the court that the accused person was arraigned before the court on 7 December 2010, and charged with two counts of stealing by person employed in the public service and abuse of office.

He said in support of the first count, the particulars of offence alleged that the accused person between 2006 and 2007 in Banjul stole 67 pellets of cocaine recovered from the stomach of one Samuel Okafor, (deceased), which property came into his possession in his position as the then deputy Director of NDEA.

He pointed out that the particulars of offence in support of the second count alleged that the accused, Karamo Bojang, between 2006 and 2007,whilst employed in the public service, abused the authority of the office by stealing 67 pellets of cocaine and then claiming that the said drugs were destroyed in a destruction exercise.

He said the accused person denied the charge, and it was not until the 27 April 2011, when the first prosecution witness testified.

The magistrate added that at the close of the prosecution’s case, the defence counsel filed a no-case-to-answer submission on 19 May 2011, and in a ruling delivered on 13 July 2011, the no-case-to-answer submission was overruled and the accused was called upon to enter into his defence.

He said at the close of the defence case, both sides filed briefs which were all thoroughly read.

“It is a basic principle of law that the evaluation of evidence and the ascription of probative value to such evidence are primary functions of court of trial which saw, heard and assessed the witnesses while they testified before it,’’ he stated.

He added that in the instant case he never saw any of the witnesses nor did he hear or observe their demeanour, while they testified in the witness box.

“Only evidence contained in the file guided this decision,” he said.

He said that it was an entrenched part of the constitution that every person who was charged with a criminal offence shall be presumed innocent until he or she was proven or has pleaded guilty.

“As such, the burden of proof in a criminal case in both sense of the term lies on the prosecution throughout the case,” the magistrate said.

He pointed out that to be able to have a conviction, therefore, the prosecution must fully discharge its legal burden of proving the guilt of the accused beyond reasonable doubt.

He added that the prosecution has called two witnesses, and the accused testified in his defence and called two other witnesses.

“It is clear from the above text of our law that for the offence of theft or stealing in our jurisdiction to occur it must involve the physical act of taking,” he said.

It was common sense that for taking to take place there must be physical contact between the taker and what was alleged to have been taken. This in his view was an important issue that the prosecution must prove in their evidence, he said.

In addition to the accused person’s testimony, defence witness 2 and 3, who were the Director General and Operations Director of NDEA at the material time of the case, told the court that the accused was neither an exhibit keeper nor does he handle the keys to the safe where hard drug exhibits are kept. They stated that the said safe was simply placed in the accused person’s office as a control or security measure, but the exhibit keeper, Alieu Jassey handles the key, he said.

“The accused himself also gave his job description to the court and in that job description it is clear that he was not an exhibit keeper nor does he work in the charge office, as he was then the Deputy Director General,” Magistrate Jallow said in his judgment.

He said PW2 clearly told the court he was not present when PW1 allegedly handed over the 67 pellets of cocaine to the accused.

“I wish to state here that the prosecution did not in any way contradict the above evidence of the defence witnesses, and I wonder how a court of law in a situation like this could ignore the sworn and unchallenged evidence of two competent witnesses. I therefore hold that the prosecution did not provide satisfactory evidence to the court to show the accused, being the then Deputy Director General of NDEA, was also an exhibit keeper at the same time,” said the magistrate.

Conversely, if the accused was not the exhibit keeper, how then did the accused come into possession of the said 67 pellets of cocaine as alleged in the particulars of offence of count one, asked the magistrate.

He said the only prosecution evidence that seems to suggest that the accused had even seen the said 67 pellets of cocaine, before the drug destruction exercise of 2009, was the testimony of PW1 alone.

No other witness was called, not even Alieu Jassey, the exhibit keeper who’s evidence had shown he was still working for the NDEA at the time of the trial, and no documentary or other form of proof has been provided.

The trial magistrate further adduced that in view of the fact of a strong denial by the accused that he ever came into direct contact with the said 67 pellets of cocaine, other than at the drugs destruction site, the prosecution needed to provide more convincing evidence to draw sufficient nexus between the accused and the alleged stolen property being the 67 pellets of cocaine.

“The prosecution’s evidence before the court did not show that the 67 pellets of cocaine at any one time came into the possession of the accused,” he added.

“It is therefore held that the prosecution had failed to show in its evidence any contact between the accused and the 67 pellets of cocaine. That been said, the court is convinced that there is not much need to discuss the entire evidence adduced in defence since it is trite law that the prosecution’s case must succeed or fail on its own strength, and not to depend on the case of the defence,” he stated.

It was therefore held by the court that the prosecution has not proved the elements of the offence of stealing as charged in count one to the required standard to enable the court grant a conviction, said the magistrate.

Regarding the second count, he went on, it was very apparent on the face of the charge itself that count 2 entirely depends on the success of count 1, the particulars upon which count 2 was premised.

“It follows from the above that if the allegation of stealing referred to therein failed, then the allegation of abuse of offence will also subsequently fail as the alleged stealing was the substance of the abuse of office being referred to,” he stated.

“In conclusion, it was worth mentioning that it was a fundamental tenet of criminal law that no man was to be condemned on suspicion alone. There must be evidence which proves his guilt before he is pronounced to be so.”

“In consideration of the aforementioned, the accused person is hereby acquitted and discharged on both count 1 and count 2 respectively,” the magistrate declared.

Read Other Articles In Article (Archive)

NDEA exhibits keeper testifies in Bun and Co Trial

Mar 11, 2011, 11:29 AM