“We help communities develop their project idea, help with training, funding, and capacity building. This is to ensure continuity of the project activities as we move to new projects or to new communities. We are constantly looking for new ways to help communities,” said Ms Isatou Ceesay.

The initiative’s director, Isatou Ceesay, who recently completed a tour of the US promoting her children’s book on recycling, passionately believes that waste reprocessing offers women a route to economic empowerment.

It is women who are in charge of waste and they are dedicated to their communities, and can really contribute a lot, she said.

“In terms of education, we are the ones who are always behind. Boys are chosen to go to school. When we conducted our training, we found women can do a lot, but don’t know who they are, or how to implement things,” she said.

After the reprocessing sessions, the community recycling project provided a week’s training activity to help participants form their own businesses or social enterprises, she added.

“The idea is that this knowledge will cascade through the communities, with women encouraged to organise their own training events after completing the course.

“It is women who are in charge of waste, and they are dedicated to their communities, and can really contribute a lot,” said Ceesay.

The project also worked with young people and the waste pickers who work on unregulated dump sites.

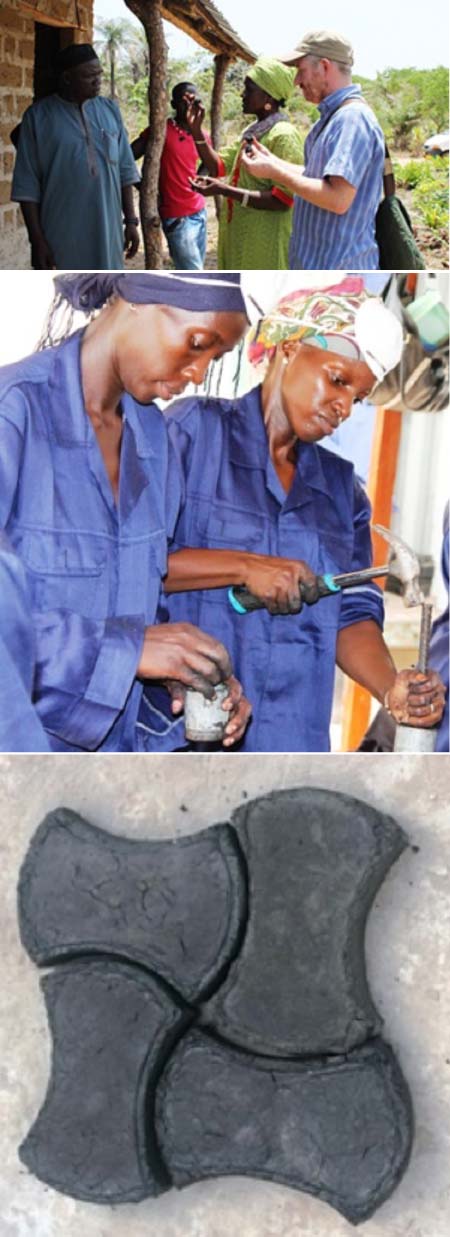

As well as organic fuel briquettes, the women learned how to turn plastic bags into paving slabs, although plastic bags were banned by the government in July, and fish and food waste into fertilizer, she added.

The volunteers were trained to press charcoal-dried mango leaves into moulds to make organic fuel briquettes, which can be used as an alternative to traditional charcoal, at the Gambia’s first recycling training centre.

According to her, women had travelled 20km from Tawto village to learn about waste reprocessing techniques at the Recycling Innovation Centre, purposely built by the newly-formed NGO.

She said five coastal communities are involved in the enterprise namely, Kartong, Banjulinding, Sifoe, Mamuda and Tawto, which is aiming to teach people about good rubbish management and, crucially, how to turn waste into wealth.

In keeping with the spirit of the project, the trainees decided to call themselves Fay Fengo Nafaa-Siyata, which means “making waste useful” in the Mandinka language.

The training gives hard-working women another option as they struggle to earn enough money for their families.

“I was making soap, but I lacked the business education to make any money from it. After paying for the ingredients I would only have 100 dalasi [$1.64] to pay for food,” said Rohey Jallow, 48, who has five children.

Nyime Dibbo, 27, said: “It is very important for women to have skills for empowerment, to learn something new. We have already missed out on school.

“When we learn as mothers, we can teach our children how to have a better life. Not everyone can work in an office. This is something you can do for yourself, and your family will grow up with this system.”

The five-month EU-funded community recycling project aims to illustrate the benefits of focusing on livelihood creation from waste in low-income countries, where effective waste management is lacking.

The idea is that these projects can reduce damage to public health and the environment from mismanaged waste, as well as alleviate poverty by creating jobs.

In The Gambia, the community organisation WIG has been educating communities about the hazards of burning rubbish, and teaching them how to recycle, since 2009.

These techniques are already in use in neighbouring countries. For example, the Waste to Wealth programme run by the UK-based Living Earth Foundation has trained slum dwellers in Sierra Leone and Cameroon to form social enterprises producing charcoal briquettes and plastic slabs.

“This is the first project to train people in reprocessing techniques across the waste streams,” explained Mike Webster, the project manager from the WasteAidUK initiative, which delivered its inaugural project with the livelihood NGO Concern Universal.

“There are plenty of reprocessing projects that haven’t got off the ground because the technology is out of reach for most people. We have focused purposefully on entry-level systems that can be made locally, and the waste materials that are actually here, not a western perception of what should be recycled.

“It was really important to partner with a local organisation with strong community links. This is as much about behaviour change and finding new ways of incentivising waste management. Our focus groups showed that even a tiny financial incentive can make for effective collection systems, people are really interested in learning how to make income from waste.”

Ceesay reckoned the briquettes sold in Brikama market could bring in 800-1,000 dalasi a day; the median income for a low-skilled worker in Gambia is 1,500 dalasi a month.

For trainee Njaba Ndow this could secure her family’s future. “My aim when I start this work is to send my daughter to school because I regret not going to school. I want to help her have a better life.”

The initial funding for the project ended last month, but Webster is optimistic that the approach has legs. “It is already spreading out beyond the coastal region. The WIG has started training communities in The Gambia’s Upper River Region, the furthest region from the capital, Banjul, as well as crossing the border into southern Senegal,” he said.

But he warns that a lack of funding for waste management will continue to hold back development.

“That is why the GWMO [report] is so important. Solid waste has long been neglected by the international donor community. In 2012, it accounted for just 0.2 per cent of development spending. Until these changes, the filth and harm it causes the poorest communities just won’t go away.”