As

we celebrated the end of Jazz Appreciation Month which ended with the

celebration of International Jazz Day we want to take this opportunity to share

with our esteem readers a brief history of jazz.

We

begin with a synopsis of the history of jazz in order to put it in proper

perspective and to recognize the invaluable contribution of African Americans

to the development of America’s most recognized cultural art form.

We

are encouraged in our effort by the opening of the museum of African American

history by the first African American President which was done sometime last

year before the end of his term. This is

not a coincidence, but a natural development in the evolution of America’s

history.

In

previous notes, we traced the origins of jazz to the slave dances at Congo

Square, now called Louis Armstrong Park in New Orleans.

Although

there is an inclination to view the intersection of European-American and

African currents in music as something theoretical or metaphysical, the storied

accounts of the Congo Square dances provide us with a real time and place of an

actual transfer of a complete African ritual to the native soil of the New

World.

In

the Americas, the dance became known as the “Ring Shout” which describes the

clusters of individuals moving in a circular pattern, chanting and wailing as

they danced around.

It

has been observed that this tradition persisted well into the 20th century, and

was still practiced in South Carolina as late as the 1950s. In fact, the Congo

Square dances were hardly so long-lived, as there are indications that the

practice continued, except for a brief interruption during the Civil War, until

around 1885.

Such

chronology implies that their disappearance almost coincided with the emergence

of the first jazz bands in New Orleans. It should be noted here that this

transplanted African ritual lived on as part of the collective memory and oral history of the black community in

New Orleans, which in turn, shaped the “self-image” of the early jazz

performers as to what it meant to be an African-American musician.

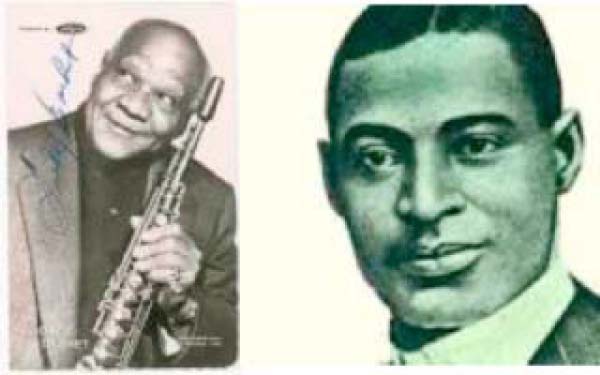

Historical accounts credit Buddy Bolden as the

earliest jazz musician, but it is also said that by the time Bolden and another

musician Sid Bechet began playing jazz, the Americanization of African music

had already began, and with it came the Africanization of American music.

(Bechet was a clarinet player from New Orleans who was at that time compared to

Louis Armstrong as a great improviser during those transitional years.)

The

story of jazz and its development is directly linked to the founding and growth

of New Orleans as a city. New Orleans went through a few hands before it became

an American city.

Almost

less than half a century after the city’s founding in 1764 by the French, it

was ceded to Spain, and it was not until 1880 when Napoleon succeeded in

getting it back. However, this renewed French control did not last long, for in

1883, the city of New Orleans was transferred to the United States as part of

the Louisiana Purchase.

The

early settlement of French and Spanish migrants played a decisive role in

shaping the distinctive ambiance of New Orleans in the early part of the 19th

century. Other European migrants from countries like England, Italy, Ireland

and Germany also settled in New Orleans and made substantial contributions to

the development of the local culture. The city’s black inhabitants were equally

diverse, many coming from West Africa and many more from the Caribbean joining

native-born Americans.

It

is said that in 1808, as many as 6000 refugees from Haiti arrived in New

Orleans fleeing the Haitian revolution. This ensuing amalgam blending an exotic

mixture of European, Caribbean, African and American elements, made New Orleans

and the state of Louisiana the most seething ethnic melting pot in the New

World.

In this society, the most forceful creative

ingredient came from the African-American underclass. This should be of no

surprise, for by 1807, about 400,000 native born Africans were transported to

America mostly from West Africa, deprived of their freedom and torn from the

social fabric that gave structure to their lives. They struggled hard to cling

on to elements of their culture, and music and folk tales were the most

resilient of these.

The

drum became a very powerful means of communication and African elements in the

slaves’ music became evident. This unfortunately led to the banning of drum use

by the slaves in states like Georgia. It was a turning point in the evolution

of the slave songs, and out of this development, came the “work songs” which

were more African in nature. This ritualized vocalizing of black American

workers with total disregard for Western systems of notation and scales, came

in various forms, and the history of jazz is closely intertwined with many of

these and other hybrid genres of music.

Generalizations

about African music are tricky and can be confusing. Many pundits have treated

the culture of West Africa as a homogenous and unified body of similar

practices. As a matter of fact, many different cultures contribute to the

traditions of West Africa. However, there are a few shared characteristics amid

this plurality which always stands out, and appears repeatedly in different

guise, in jazz.

One

good example, is the call-and-response forms that predominate in African music,

and is also found in the ‘work songs, the blues and jazz.’ It should be noted here that the most

prominent characteristic, i. e. the core element of African music in its

contribution to the development of jazz, is its extraordinary richness in

rhythmic content.

The

ability of African performance arts to transform the European tradition of

composition while assimilating some of its elements, is perhaps the most

striking and powerful evolutionary force in the history of modern music.

The

relationship between jazz and the blues is always a subject of discussion among

scholars of music, and the early accounts of slave music are strangely silent

about the blues.

Research

has been done by some scholars to discover the surviving traces of the

pre-slave origins of this music.

The

music called Blues is often associated with any sad or mournful song, but this

is a misnomer as the term blues is a technical word which refers to a

twelve-bar form that relies heavily on dominant tonic sounds and subdominant

harmonies. This particular technique is known to have spread beyond the blues

idiom into jazz and many other forms of popular music.

There

have been attempts to trace the lineage of early blues singers as a

continuation of the West African tradition of griot singing, but blues

historian Samuel Charters summed it up in his findings as follows , “ Things in

the blues had come from the tribal musicians of the old kingdoms, but as a

style the blues represented something else.

It

was essentially a new kind of song that had begun with the new life in the

American South.” As the blues progressed and started leaving its mark on this

musical transition, so also was Ragtime developing with equal importance or

more, as a predecessor to early jazz.

With

ragtime came the stride piano and indeed in the early days of New Orleans jazz,

there was a thin line between ragtime and jazz performance and the two terms

were used interchangeably.

After

the advent of ragtime, the development and transition of jazz music took a

different and progressive direction, encompassing all other forms and styles of

music to make it universal and far-reaching. The story of this transition

cannot be exhausted in this little piece but we hope you have enjoyed reading

about jazz as we continue to share with you some valuable information about

this beautiful music and its history.