As

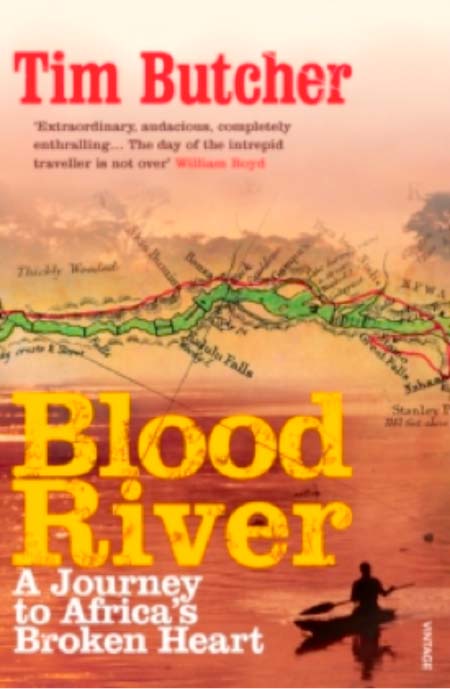

a journalist Tim Butcher had covered stories from all over war torn Africa, but

it was the system of corruption and secrecy veiling the Congo that sent him on

an adventure quite unlike anything he had done before in his book Blood River.

Following in the trail of the explorer H. M. Stanley, who was the first to map

out the interior of the Congo in 1874, Butcher traded the comfort of hotels and

aeroplanes for the back seat of a motorbike and the traditional pirogue, a

canoe hollowed out of the trunk of a tree.

Starting on the Congo’s eastern border in a small ghost town that reeked

of colonial decay, the author set out on

what many declared an impossible task: to follow the Congo River from its source

all the way to Boma in the west, just short of the river’s mouth.

In

the wake of a 2003 peace agreement thought to put an end to one of Africa’s

bloodiest wars, the country Butcher explored showed no signs of the stability

the outside world may have expected. Throughout his journey he was warned off

by UN workers and government officials, but somehow still managed to find

people brave enough to risk their lives to help him on his way. Benoit and

Georges, two such figures, accompanied the author through the dangerous bush of

the Katanga province, where the mai mai, one of the most feared tribes of the

eastern Congo, are traceable only through word-of-mouth and the destruction

they leave behind them.

Walking

a thin line between adventure tourism and something more substantial, it is the

author’s great knowledge of the country’s history, his ability to convey scenes

and characters in crisp prose, and his interpretation of the complex situation

of the Congo today that saves this story from becoming another outsider’s

account.

There

are the poor who struggle beneath their loads of palm oil for hundreds of

kilometres living only off of fresh water and food that they can forage in the

bush, for pay that translates into almost nothing. There are the tribes whose day-to-day

existence revolves around fleeing from armed rebel forces, only to return to

villages that have been plundered and destroyed. And then there are the

foreigners, the traces of a colonial system of greed still in place, taking the

country’s mineral wealth with little more than small payments made to corrupt

officials going back to its people.

Butcher

had not only the courage, but the insight to tell a great story of a country

struggling to emerge from a history of colonial rule, bearing the brunt of the

modern world in all its indecency.

The

current situation of the Congo can be summed up well in the words of a mayor

Butcher encountered in a small town in eastern Congo: “I am the mayor,

appointed by the transitional government in Kinshasa. But I have no contact

with them because we have no phone, and I can pay no civil servants because

there is no town or post office where money could be received, and we have no

civil servants because all the schools and hospitals and everything do not

work. I would say I am just waiting, waiting for things to get back to normal.”

Available

at Timbooktoo, tel 4494345.