Isatou

Jeng was never told why she was taken under the knife but as she grows to

maturity, to womanhood, she realised that she is without a clitoris.

“When

I realised that my clitoris was missing, the only explanation I got was ‘we did

it to purify and protect you as a woman’,” she said as she narrated her story

of being a survivor of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM).

The

young woman said the trauma of going through FGM multiplies when she needs the

missing organs the most but not available to perform its functions.

The

story of Isatou is not an isolated case. According to a 2013 report, an

estimated 76.3 per cent of girls and women have been subjected to FGM and are

living with its trauma and physical consequences.

This

statistics, though among the highest in Africa, is a result of more than 30

years of campaign of demystifying FGM and delinking it to Islam.

The

initial sign of the success of the campaign was not visible in terms of numbers

but by making FGM a household topic of discussion; initially it was a taboo

that no one dares talk about or challenge.

But

the campaigners, undeterred and undiscouraged by the modest statistical

achievement, continued the advocacy until eventually, they got the political

commitment of the government of Yahya Jammeh, the former president.

Barely

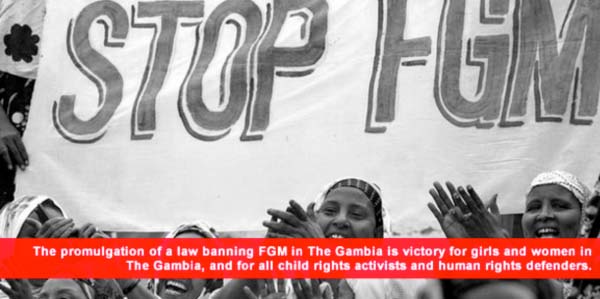

two months after Jammeh’s declaration to abandon FGM, the National Assembly in

December 2015 promulgated a law ‘to prohibit female circumcision due to the

proven harmful nature of the practice’.

The

legislation has created an enabling environment for the advocates to take an

active role in protecting women and girls and increased community awareness of

FGM’s harmful impacts.

But

as the world celebrates the International Day of Zero Tolerance to FGM today,

Monday, anti-FGM activists in The Gambia said the new government should do

more, not just be complacent with the fact there is already a law against the

practice in the country.

Activist

said the passage of the law was the beginning of the Gambia’s commitment to

have zero tolerance to the practice.

Njundu

Drammeh, coordinator of Child Protection Alliance (CPA), said enforcing the law

is what is needed now; the new government should make sure that the law is

fully enforced to make it meaningful.

Advocates,

he said, should also continue to popularise the law by sensitising people of

its existence particularly on days like the International Day of Zero Tolerance

to FGM.

He

said anti-FGM stakeholders should continue to work together to disabuse the

minds of the parents and communities by helping them to unlearn all the things

associated to it.

Mr

Drammeh also pointed out that circumcisers should be economically supported so

they are able to stop the practice.

From

2007 to 2013, a total of 128 circumcisers from 900 communities have abandoned

the knife, decisions that were all publicly declared in ‘Dropping of the Knife’

celebrations courtesy of Gamcotrap, a local women’s rights NGO.

These

women do not just have prestige on circumcision but also money. Mr Drammeh said sensitising them to drop the

knife is not enough they need to know have an alternative source of livelihood.

FGM

board needed

Lisa

Camara, coordinator of Safe Hands for Girls, said the new government should put

in place more policies, and set up an FGM board that will oversee the

enforcement of the law and the implementation of the policies so as to make The

Gambia FGM free.

She

said a lot of people in the country, especially in the provinces, do not know

who to report to, and how to report issues of FGM.

Ms

Camara said Safe Hands for Girls, through the help of The Guardian, would

continue working with the media to amplifying voices on FGM.

She

said her organisation would celebrate the international anti-FGM day next month

using art and music to send out FGM messages that could be communicated.

Safe

Hands continue to embark on ways and means of sensitising people about FGM

because for them, using the law to punish the people is a non-starter.

“The

more information, the less we come across FGM cases,” Ms Camara said.

For

Fatoumata Touray of the Gambia Committee of Traditional Practices (GAMCOTRAP),

there should be vigilante groups set up in the communities to monitor those

communities that are still practicing FGM.

“These

groups will be capacitised to serve as FGM watchdogs for civil society

organisations,” she said.

“They

will raise the alarm whenever a particular community is about to practice FGM

so that early intervention can be done to safe the lives of the innocent girls

instead of just punishing the perpetrators after the damage is done on girls

already.”

As

Isatou, the FGM survivor, is now a matured lady, she has joined the campaign

against FGM so that she can help make sure that innocent girls are speared of

the trauma she is living with as a result of FGM.

“I

am also calling on the government of President Adama Barrow to show more

commitment by making FGM a top priority in its drive to promote and protect the

rights and welfare of women,” she said.