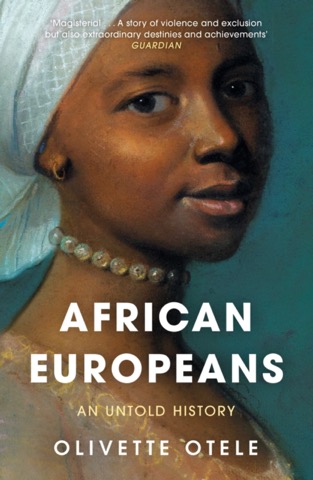

Among the private drawings of the great Renaissance artist Albrecht Durer are two moving likenesses of African Europeans – so vivid and timeless you half expect them to look up and come to life. In Nuremberg in 1508, he sketched a young man with a small beard wearing a simple cloak. A decade on, lodging with a Portuguese merchant in Antwerp, he captured the image of a young woman of the household. “Katharina, 20 years old”, Durer wrote above her portrait, to remind himself of their encounter. Later, designing his own coat of arms, he centred it around the bust of a Moor.

As Olivette Otele shows in her fascinating book, there was nothing very exceptional about any of this. By the 16th century, the black presence in European life and culture took many forms, and there was a long history of Africans living on the continent. Durer could as easily have met such persons in Italy, Spain, or the Low Countries, as in the heart of Germany. And, in linking his own status explicitly with the image of a black man, he was probably following a heraldic tradition inaugurated by the Hohenstaufen emperors themselves.

Of course, like all people, Europeans had a tradition of eroticising and “othering” people of alien lands and cultures. But for most of European history, religious difference was a far more important vector of prejudice than skin colour or geographic origin. Throughout the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, the divide between Christians and Muslims trumped most other considerations. Before the 17th century, there is much less evidence of preconceptions about Africans per se – certainly compared with the virulence of Christian antisemitism, or the racialised notions of inferiority projected by some white-skinned groups on to others, such as the English on to the Irish.

Even “Europe” and “Africa” were only weak labels. The distance from Sicily to Tunis is the same as from London to Paris, and the peoples living around the Mediterranean had always mingled with each other. Among the north African rulers and notables of the Roman empire were the emperor Septimius Severus; Marcus Aurelius’ ‘s tutor, the consul Marcus Cornelius Fronto; and the rhetorician and novelist, Apuleius. Later medieval Egypt was governed by the Mamluks, white African Muslims of European descent. Frederick II, king of Sicily (and, from 1220, Holy Roman emperor) welcomed Africans to his court, employed many of them in his service, and even made one (John “the Moor”) his lord chamberlain. Until the end of the 15th century, Arab and north African Muslims ruled over most of the Iberian Peninsula; a few years later, the first Medici duke of Florence, Alessandro, was born to an African mother.

In the Roman empire, where African Europeans begins, ethnic origin was always marginal to civic identity. The medieval church was based on a similar ideal, in which dark-skinned Christians exemplified the faith’s universal power. From the later middle ages, black saints became more prominent, as connections grew between Ethiopian and European Christians, and new African converts were promoted and canonised. Henrique, son of the king of Congo, became a bishop in 1518; St Benedict of Palermo was the child of parents from sub-Saharan Africa. The best-known cult was that of St Maurice the African, patron saint of the Holy Roman empire, whose image was venerated in sculptures and paintings.

Slavery and serfdom were common across classical and medieval Europe and Africa. But the rise of the transatlantic slave trade, and the new notions of racial inferiority that Europeans increasingly invented to justify its horrific, unprecedented scale, transformed the perception of Africans after 1700. It also created a huge, lasting population of European and colonial men and women of mixed heritage. Otele is particularly attentive to their varying identities and experiences – as she is to the agency of women and the dynamics of gender, and to the selective amnesia and racial prejudices of different European societies, whether Dutch, Danish, Italian, Swedish, Russian, French or German, from the 18th century to the present.

One of the book’s great pleasures is its cast of memorable characters. Take the former slave Juan Latino, who became a noted humanist poet, scholar, and teacher, and married one of his Spanish pupils. Or Jacobus Capitan, enslaved as a child, who was educated at Leiden University, wrote a Latin dissertation defending slavery, and returned to the Gold Coast as a missionary for the Dutch West India Company. Who wouldn’t want to meet Joseph Boulogne, the rich, dashing French revolutionary soldier, fencing master, playwright, violinist, and composer – or Jeanne Duval, unapologetic sex worker, artistic model and muse and lover of Baudelaire?

Though this is a work of synthesis, it’s an unusually generous and densely layered one. Otele is not just concerned to tell the life stories of her protagonists, but also to follow their changing portrayals after death – as well as explaining how and why they’ve been differently interpreted by generations of previous scholars. To this end, she constantly toggles between different centuries and perspectives. This can seem awkward, but it underlines her central message: what we see in the past, as in the present, is constantly in flux. It depends on our priorities and presumptions. As she argues, providing multiple and more inclusive histories can empower people, and help discredit and dismantle racial injustice in the present.

Available at Timbooktoo Tel:4494345,5033448