With the protectorate peoples resident in Bathurst and the environs transforming their charitable societies into a cohesive force that the veterinary surgeon David Kwesi Jawara baptised the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) in February 1959, politics was taking on an unprecedented momentum. Opportunity for power in government was palpable enough to swing masses under the banner of this new party that was taking centre stage with the Democratic Party (1951), the Gambia Muslim Congress (1952) the United Party (1952), and the Gambia National Party (1958).

One of the voices that emerged with the sweep of the PPP belonged to Baba (Ba) Musa Tarawally, a young man with penchant for writing shown quite early when he sent unsigned letters to the editor of the Gambia Echonewspaper in Bathurst while he taught in primary schools in Ballangharr and Essau in the provinces. Education officer, Mr Cawkell paid a price; Tarawally was bent on exposing the officer’s lewd tricks with female teachers he posted in the provinces. Desperate to know the source of the articles, Education Director Alexander N. Gregory wrote to Tarawally to ask if he would know of anyone in his staff who might have knowledge of the origins of this pamphleteering he called ‘The Kudang Times.’

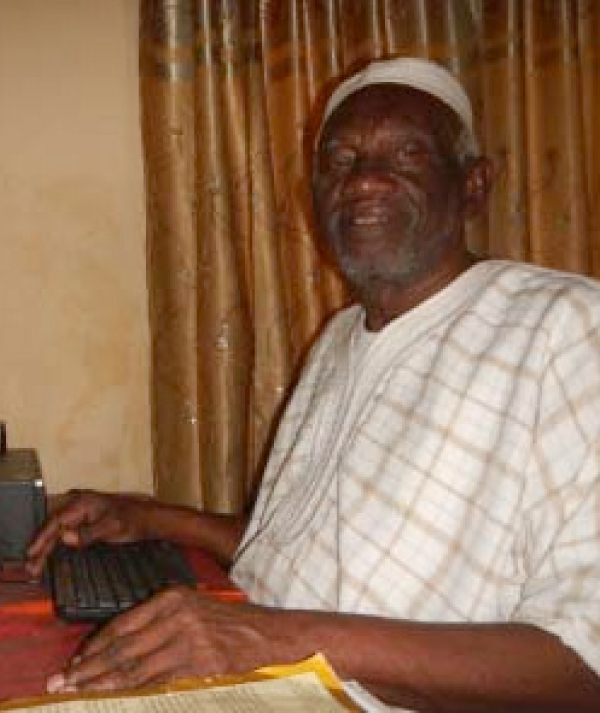

Tarawally had set himself on night watch, and remained on watch through his sojourn here of 90 years from 1930 until the end came on Monday March 1, 2021. His writing skills came in handy whenever he wished to influence opinion in the new political party and to find his place among his peers. In 1959 he was promoted to headmaster and now fully juggling school and politics. Almost immediately, he openly disagreed with the central party authority on their selection of candidates to stand in the Niumi/Jokadu area in the first-ever general elections in the country in 1960. It was a tough call but L.O. Sonko the party’s candidate of choice was selected and finally elected. Then there came a sudden directive redeploying the headmaster to Kudang, in Niamina East district in today’s Central River Division. Tarawally considered this relocation a move to send him far away from the heartbeat of the party; to the eager, angry and outspoken political commentator, this was exile.

With only writing at his disposal with which to influence the constituency Ba Tarawally used it to good effect. His physical robustness commanded a presence, and he promoted no less his bold voice and his quick pen. Of the PPP he wrote openly and critically, going against the grain inside his own party and chastising the leadership of a party he consciously recognised as an ethnic bastion and power base of the Mandinka people that had tradition and culture to guide it. Baba Tarawally and D. K. Jawara were soon at loggerheads over the issues in the Mandinka caste system. Tarawally questioned the choice of Jawara, the one the PPP had asked in 1959 to resign his government job as veterinary officer to lead them. (See The Gambia Outlook and Senegambia Reporter, June 20, 1960, p1.). The maternal end of Jawara’s heritage was from low caste leather smiths from Karoniand conservative Mandinka tradition held that only royal or chiefly blood would rule or govern. Jawara in his autobiography Kairaba(2009) dismisses the caste system as abominable and an archaic distraction from people’s human rights to take part in national politics and to govern if necessary. Then, the ‘cult’ syndrome developed around the personality of the new party leader, Tarawally would complain bitterly after a few years that: “D.K. Jawara had become the PPP and the PPP had become D.K. Jawara.” It would prove a tough fence to mend between the two men and which would last throughout their careers in politics.

Meanwhile self-government had increased the tempo in local politics and political expression. Early in 1962 the PPP Government in office was already holding talks in London for full independence in fulfilment of a standing agreement by all parties that the winner of the General Election that year could initiate those independence talks. Ba Tarawally was now teaching at the Crab Island School in Bathurst a posting that guaranteed his presence within the pulse of national politics which had taken him over completely. Conscious of the leverage his writing gave him to be heard within the party, he started a mimeographed newssheet in October 1962. He called it The New Gambia and threw it fully behind the party and its new mission in government. The newssheet became the voice of the PPP, especially opportune for attention with the premature death of The Gambia Times under Melville B. Jones.

The New Gambia gained readership quickly. Tarawally had the extra advantage of growing up in Bathurst and knowing the capital community well after years of living with the prominent Krio family of T. B. Williams of Louvel Street, Bathurst. That made him an asset for the PPP that was struggling to gain acceptance in the capital town that was still considering the organisation as provincial and too overtly ethnic. For a man too outspoken at times for the comfort of some of the younger and inexperienced men at the helm of the party committees, Tarawally’s role as the editor and mouthpiece of the party was sometime worrisome.

And, indeed, holding sway over the party’s news organ came with its share of woes; not everyone was comfortable with the kind of authority editorial control gave Tarawally. The party and its leader Jawara began to worry over the radicalism of the editor. While much of the rancour would be managed in-house, some of it spilled disastrously. In 1966, only one year into independence, the decision by the party executive to expel a senior member, Lamin Bora Mboge, from the PPP would cause severe a rift. Tarawally was convinced that the expulsion bid was anchored in more deep-seated animosities among the younger elements jockeying for personal power. This pitched the editor against the powerful inner cabal. The party leader was rather more receptive of feelings of the others since he would like to see the editor’s opinions and attitudes brought under control. When Tarawally lost the debate on the expulsion of Bora Mboge, he resigned from the party in protest, taking his newssheet with him.

Thereafter, The New Gambia ceased publication for a few months but reappeared in 1971, revamped and registered as a privately-owned newssheet. Tarawally was bent on settling scores. His insider knowledge of the PPP gave him the advantage of pinpoint accuracy in his exposure of the government and the party. He was set to blister the tender fabric of the PPP and some of the tenderfoot politicians who opposed him. The New Gambia set itself on the road to undo a system it had helped to set up, and there were plenty of enemies poised to stop him. Tarawally said he knew of the devastating use of ‘covert economic warfare’ as a tool by government against its opponents. He said a man without food had no legs to stand on in the political arena. Since he could not count how many opponents the PPP had brought to their knees by the shutting off of their economic supply line, keeping proper books and ensuring that his newspaper fed and clothed him were of the highest priority. Those city-based opponents to the government but totally dependent on civil service jobs were to be the worst hit by this secret policy weapon of the PPP.