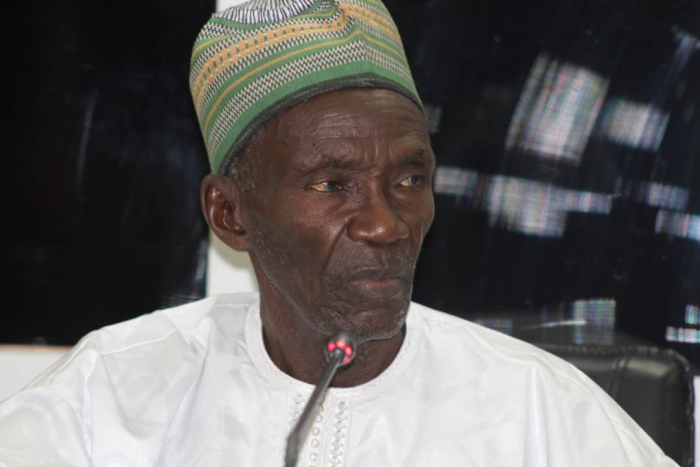

Keynote Address by FaFa Edrissa M’Bai

Published in 2012 by Fulladu Publishers

This keynote address was delivered on the occasion of the Gambia Bar Association Conference on Legal Practice Ethics and Advocacy held at the Jaama Hall, Kairaba Beach Hotel on Friday, 29 January 2010.

After the glittering, but not unusual, brilliance and erudition of Mr Cherno Jallow QC, Attorney General of the British Virgin Islands, our eminent and distinguished advocate from California, Mr Edrissa M O Faal, my very charming and most Learned Friend, Ms Ida D Drameh, the formidable Deputy Chief Prosecutor General of The International Criminal Court, The Hague, Mrs Fatou Bom Bensouda, Mr Robert Hutley OBE, Coordinator of DFID, not to mention the great scholarly prophesies of the distinguished Professor from the antipodes, Professor Kim Economides, Professor of Law and Ethics of Otago University, New Zealand, it is obvious that there is nothing more to say and that any attempt to do so will be no more than trying to re-invent the wheel. And I feel uneasy lest I prove unequal to my task, for the difficulties that lie before me in trying to follow on the giant footsteps of these distinguished men and women of the law are many and obvious. I therefore make no apologies for what may be an unlimited length of time for you to have to endure all the rubbish that I will now inflict on you.

In the Preface to his book, The Ideas in Barotse Jurisprudence which is the published Stores Lectures he delivered at The Yale Law School in 1963, Professor Max Gluckman, the distinguished avant-garde Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Manchester, tells us that: ‘When Professor A E Housman was appointed to the Chair in Latin at the University of Cambridge, Trinity College staged a dinner in his honour. It is said that he began his reply to the toasting of his health thus: “I am told that in these halls Porson was once seen sober, and Wordsworth was once seen drunk. A finer poet than Porson, a better scholar than Wordsworth, I stand before you tonight betwixt and between.”

At Yale, Professor Gluckman puts it this way: “In this lecture I too stand betwixt and between – a better anthropologist than some lawyers, a finer lawyer than some anthropologists, if I stagger somewhat in the attempt to acquit myself, I plead for your forbearance.”

Like Professor Housman at Trinity College, Cambridge, and Professor Gluckman at The Yale Law School, but a far much lesser mortal and therefore worse than either, I too stand before you betwixt and between – the Honourable Attorney

General and Minister of Justice and the Lord Chief Justice of The Gambia. If therefore I stagger somewhat in the attempt to acquit myself, I too plead for your forbearance.

Ruskin, in The Essays: Unto This Last, suggests that “Five great intellectual professions relating to the daily necessities of life have hitherto existed in every civilized nation: The Soldier’s profession is to defend it. The Pastor’s to teach it. The Physician’s to keep it in health. The Merchant’s to provide for it. The Lawyer’s to enforce justice in it.”

I chose the lawyer’s profession. But before I came to Law I had tried economics; I had tried literature, and I had tried sociology. None did work. My interest in literature ended very early when I was required to discuss that “Shakespeare is a woman.” That was the day I bade farewell to literature. For the same reason, I abandoned sociology after a Sessional Examination Paper in which the first question read something like this: “When an Englishman quarrels with his wife, he goes to the garden; a Frenchman to his mistress; an American to his attorney; an African marries another wife. Discuss.” But I think economics confused me

even much more. I could not reconcile the profound simplicity of Adam Smith that “if you can teach a parrot to say ‘supply and demand’ you have made an economist of him” with the significance of Professor W Arthur Lewis that “economics is too important a subject to leave in the hands of economists alone.”

I decided to stay in law: charmed by my great fascination for the spoken word, the formulated idea, the expressed thought and the system of logic manifest in its study. Our subject this morning, therefore, will be neither on the mind of Wole Soyinka nor the poems of Lenrie Peters, nor the unintended consequences of intended actions nor the mystery of capital nor why capitalism triumphs in the West and fails everywhere else. All these are worthwhile subjects for other lectures. Our subject this morning is: “We Are Called to Leadership: The Enduring Responsibility of Lawyers.”

“The law is the bedrock of a nation; it tells us who we are, what we value… Almost nothing has more impact on our lives. The law is entangled with everyday existence, regulating our social relations and business

dealings, controlling conduct which could threaten our safety and security, establishing the rules by which we live. It is the baseline.”

I have taken the foregoing from the book, Just Law, published in 2004 by one of my favourite authors, Baroness Helena Kennedy, QC, woman activist and Chair of the British Council. I wish only to add that the law is the lifeblood of a nation.

Sometimes I feel alarmed at the all-encompassing functions of the law. I feel alarmed because like everyone else here I am overwhelmed at the sheer awesomeness of the responsibility we all must bear by dint of our calling. For the work we do is a calling, a vocation. Members of the public may admire our black gowns and horse-hair white wigs. Or they may be turned off by them. They may even scoff at them. Students may engage in debate as to whether our robes and wigs are the relics of colonialism or whether the time has come to discard them. But these are not our concern.

We are the priests and priestesses, the ministers of the law. When a person is ill, they need a doctor. The doctor diagnoses, prescribes, operates and does whatever else that is needed to save life. The patient lives and is happy to have the gift of life and good health.

The same persons suddenly find themselves on the verge of losing their house or their job. They may instead find they have been badly cheated in a business transaction or that they are victims of domestic violence or negligence or even that they are locked up on some trifling accusation. They need a lawyer and they need the court. Where they cannot brief a lawyer, who will sort through the maze of their problems, they begin to see that their life has no value or meaning. They soon find out too that their tablets, injections and surgery can only translate to good health and life when there is value added.

As ministers of the law, we are equipped to add that value, to give meaning to the lives of people through legal advocacy and the application of the law. The right to life is as much as the right to access to the law. For the role we play in sorting out the lives of the people and making these lives meaningful; for constantly staving off human tendencies to resort to a Hobbesian state of nature; for often finding that the saving of situations that are important to the individual would rest in the actions we take, I come to the conclusion that we are called to leadership.

When I dwell on leadership in this sense, I do not refer at all to the issues of governance. I see the leadership roles that lawyers must play in ensuring that the day-to-day affairs of persons, natural and artificial persons, are regulated by proper conduct. I see the lawyer’s role in even family relationships such as maintenance of children and custody matters. I see the hope in the eyes of anxious clients who come to their lawyer. I can almost touch the optimism of the clients who have briefed their lawyer and who sit quietly waiting as papers are drafted for filing or a letter is being written.

Ladies and gentlemen, my learned friends, ours is the noblest of the professions. Let us always remain honourable men and women. Let us never forget that we are called to leadership. In his eloquent address to the 5th Commonwealth Law Conference in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1977, Sir Shridath Ramphal, Secretary-General of the Commonwealth and former Minister of Foreign Affairs and Justice of Guyana, and an eminent jurist in his own right, was appealing to professional colleagues like us in the Commonwealth to place their talents at the service of social justice and social change in both national and global context when he said: “Our societies look to us as community leaders, as opinion formers, as advisers and as members of a profession with a belief in justice, not only for advice but also for practical leadership, not only for mere preservation of the status quo, but for making it worthy of survival, not for observance of rituals but for constructive innovation.”

In an address to the Oxford University Africa Society in March the same year, our distinguished Commonwealth Secretary-General declared: “On the issue of human rights let me be content with words which represent my most profound conviction and the principles for which I believe the Commonwealth stands on this most vital matter; let us establish as axiomatic the universality of human rights; that human rights are not divisible; that they cannot be apportioned between states and amongst peoples; that the dignity of man is everywhere affronted when the human personality is anywhere degraded; that justice must be given a worldwide dimension if injustice is not to debase our civilization and threaten the peace of the world.”

I respectfully submit that human rights will become the passion of the 21st century. And, like the distinguished Secretary-General, The Gambia Bar believes that the principles of human rights are as valid now as then, and that now as then, their validity rests upon their universality. It remains, in each case, only a matter of judgment when public invocation becomes justified, but all regimes would do well to remember that there are levels of outrage to the conscience of humankind that trigger that justification. The world would be a more shameful and more dangerous place if it were otherwise.

In the speech biography of Viscount Buckmaster entitled An Orator of Justice we read the speech on “The Romance of The Law” he delivered to the American Bar Association at Detroit in September 1925, when he said, “Our profession is the greatest to which man’s energies can be called. We are servants in the administration of justice. It is therefore a profound mistake to think that a Lawyer should be a man who by any device can secure victory in Law Courts for his clients. Every lawyer down to the youngest junior ought to remember that he, in his small degree, is assisting in something more than merely settling a quarrel between two people. He is a minister of justice.”

“What are the qualities he should possess?” he asks “He should have a sense of honour. He should have courage undefeated and faith undefiled and he should be ready to ignore at once all popular applause and popular abuse. He should remember that when the sound of public approval tickles the ears of any man, whether a Judge upon the Bench or a Counsel at the Bar, when he is flattered by the passing breath of popular favour, the administration of justice at once becomes in great danger. No fear of ill-informed censure should influence his courage. No hope of unearned praise should give him any pleasure.”

You may say to me, in all the difficult conditions of life, do you really think that such a standard as you put forward is a standard that can be obeyed? My answer is, ‘Yes’, and I say more, that if you will read any of the splendid biographies of the lives of lawyers you will find people who are notable examples of the way in which it has been carried out. I will come back to this later. But it must be admitted that it is not the common view of lawyers, and I think we ought to face the common view in order that we may show by our conduct how utterly unfounded it is.

You may remember that Thackeray described a great lawyer in these words: “He was a man who had laboriously brought down a great intellect to the comprehension of a mean subject, and in his fierce grasp of that, resolutely excluded from his mind all higher thoughts, all better things; all the wisdom and philosophy of historians; all the thoughts of poets, all wit, fancy, and reflection; all art, love, truth altogether, so that he might master that enormous legend of law. He could not cultivate a friendship or do a charity or admire a work of genius or kindle at the sight of beauty. Love, nature, and art were shut out from him.”

What a libel on a great profession to which Thackeray had once himself been apprenticed, and how utterly false! It would be more true to say of lawyers that, so far from this narrow outlook on the world, there is no horizon too large for us to gaze at, and that the subject of our work is one which, as it includes the greatest of all things, the study of human life, so it gives the greatest scope to the noblest powers of the intellect. What is the subject of a lawyer’s work? For this I would use the words of Juvenal: “Whatsoever it is that men do, their hopes, their fears, their anger, their pleasure, their vagaries, their delights, all of these things form the medley of our briefs.”

There is no learning that comes amiss to us. The most erudite, scientific work is a matter with which we may have to deal. There is no phase of all the many mysteries of the human heart which may not be the subject of the case we have to consider. There is no form of knowledge that is alien to our perfect equipment, and people who confine themselves to a meaner view are debasing a great profession.

Shakespeare also had something to write about lawyers. The character, “Dick the Butcher” drunkenly proclaimed in Henry VI Part II; “The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.” Hamlet, in the graveyard scene, held up the “skull of a lawyer” and asked Horatio, “where be his guiddies now, his guillities, his lassies, his tenures and his tricks?” But nothing dramatizes the struggle in Shakespeare’s England for supremacy between the Common Law Courts and the Equitable Court of Chancery more than the oral advocacy in Julius Caesar particularly the funeral orations by Brutus and Mark Anthony over Caesar’s corpse, or Portia’s ruling in the case of Shylock v Antonio in The Merchant of Venice.

And this reminds me of the story of King Solomon in the Bible … when he had to make a legal decision in what must be the earliest recorded custody case… in determining the real mother of the baby in question as the woman would rather give up the child than see it cut into two or even hurt.

Even the Bible refers to lawyers. In Matthew 22 verse 35: “Then, one of them, who was a lawyer, asked him a question, tempting him saying, Master, which is the great commandment in the law?” Jesus, all Christians will know, replied that “thou shall love the Lord, thy God with all thy heart, soul and body.” The lawyer was a Pharisee. The same account is narrated in Luke 10, verse 35. When Jesus said in Luke 11 verse 46: “Woe unto you also, ye lawyers! For ye lade men with burdens grievous to be borne, and ye yourselves touch not the burden with one of your fingers,” he was not admonishing solicitors, attorneys or barristers as we know it, but rather the religious teachers of the day as Luke 12 verse 44 shows: “Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites” as well as Luke 8 verse 30: “But the Pharisees and lawyers rejected the counsel of God against themselves, being not by him.”

In Islamic literature, we are told that the position of a judge was one of the highest positions of state and society, guaranteeing the one engaged in it wealth, prestige and glory. The Caliph, Saidina Ousman, once sent for the pious Abd Allah Ibn Umar and asked him to hold the position of judge but he apologized. Saidina Ousman asked him, “Do you disobey me?” Abd Allah Ibn Umar answered, “No, but it came to my knowledge that judges are of three kinds: one who judges ignorantly: he is in hell; one who judges according to his desire: he is in hell; one who involves himself in making Ijtihaad and is unerring in his judgment. That one will turn empty-handed, no sin committed and no reward to be granted. I ask you by Allah, exempt me.”

Saidina Ousman exempted him after he pledged never to tell anyone about it, for he knew Abd Allah Ibn Umar’s place in the hearts of the people and he was concerned that if the pious and virtuous knew his refraining from holding the position of judge, they would follow him and do the same and then the Caliph would not find a pious person to be a judge. However, we Muslims are made to believe that an upright judge receives the blessings of 60 years of pious worship for every just decision he gives.

I would, therefore, like every one of us, in glorifying and ennobling our profession, to refute the calumnies to which we are often unfairly subjected; that the law is a narrow subject of study and that success in it depends on trickery and device. It is nothing whatever of the kind. Knit, as you like, law with history and it becomes life, life in a movement advancing from a continuous past to a continuous future. The story and development of the laws of any society are the surest possible means of determining the progress that is made along the great path way of civilization.

Furthermore, even outside the profession itself, lawyers have, throughout the world, been called to leadership in all societies. In England, Prime Ministers William Gladstone, Benjamin Disraeli, Clement Attlee, Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair are lawyers. In Asia, Mahatma Gandhi and Pandit Nehru of India, Muhammed Jinah and Benazir Bhutto of Pakistan, Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore, and Edgardo Angara of the Philippines are Lawyers. In Africa, Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo of South Africa, Obafemi Awolowo (the President Nigeria never had), Taslim Elias, who rose to become President of the International Court of Justice at the Hague, Richard Akinjide (my good friend and mentor), Bola Ige, Denis Osadebey, H O Davies, Gani Fawehinmi and many others are lawyers. And even here in our country, P S Njie, the First Chief Minister of The Gambia, is a lawyer.

We all know that Barack Obama is the 44th President of the United States of America. But do we know that an amazing 24 of these were lawyers?: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, Abraham Lincoln, Rutherford B Hayes, Chester A Arthur, Grover Cleveland, Benjamin Harrison, William McKinley, Woodrow Wilson, Calvin Coolidge, Franklin B. Roosevelt, Harry S Truman, Richard Nixon, Gerald R Ford, William J Clinton and Barack Obama. Yes, all are lawyers!

In July, 1981 President Ronald Regan in nominating Sandra Day O’Connor to be a woman Justice of the Supreme Court for the first time in the 191 year history of that nation’s highest judicial body said: “Without doubt the most awesome appointment a President can make is to the United States Supreme Court. Those who sit on the Supreme Court interpret the laws of our land and truly do leave their footprints on the sands of time, long after the policies of presidents, senators, and congressmen of a given era may have passed from the public memory.”

Now, let me give you a few instances of the men who show the heights to which lawyers can attain. In the early part of the 18th century there was a man called Alfonso of Ligueri, who is today a saint, and whose intersession at the throne of the Most High has been sought by many thousands of our troubled fellow men and women. He was a lawyer, and in the cause of a case that he was arguing, by accident, he misquoted a document. His opponent pointed out to him that the whole of his case consisted of the misreading of the document that he ought to have known; and the man was so conscience-stricken and so horrified at the thought that he had contributed to misleading the Court, that he declined to go on or pursue the career of an advocate any longer, and the entreaties of the Judge and of Counsel, who assured him that they knew it was nothing but an error, would not reconcile him to continue his work. This must not only go to show but also emphasizes that the lawyer’s duty to the Court is higher and more important than the duty to the client. If lawyers mislead the court and unfairly obtain judgment for their client, that is miscarriage of justice.

Let me take two other instances that deal with more practical things. We are told that upon the walls of the Vatican there is a painting which possesses no artistic merit whatever, yet it gives an appeal that greater paintings and nobler statues lack, for it represents a man in mean clothes entering at an open door, and that is the picture of Farinacci, the great Italian advocate, who braved the passion of the crowd and dared the wrath of the Pope for his repeated efforts to obtain justice and mercy for his unhappy client, Beatrice Cenci, who was forsaken by the world and cut off by the Church.

Let me give you one more. In the 18th century there was a great French lawyer whose name was Malesherbes. He was a man so given to good works that he was beloved for his charity throughout the length and breadth of France. He was devoted to science and literature. He resisted to the uttermost any attempt to interfere with the dignity and the independence of the Bar, because he knew that upon that rested the independence of justice. Twice was he called to the Councils of the State; twice he had to abandon the seals of office. He was the most vigorous indicter of the abuses of the time. He declared himself in favour of religious liberty, impartial taxation and the abolition of lettres de cachet. Had his opinion been listened to, the terrors and the horrors of the Revolution might have been averted; but he was disregarded, and the storm burst. He was in safety in Switzerland following his dearest pursuit, botany and literature, when his master, Louis XVI, was brought up for trial. The old man was then 74. Others refused the office of appearing for Louis XVI, and pleaded this one, his age, and that one, some other excuse. The old man volunteered his services. Said he: “I was called to the councils of my master when all the world thought it was an honour to serve him, and shall I not serve him now when all the world deems it dangerous?” He, with his brave juniors, undertook the dangerous and impossible task of defending Louis XVI before the Revolutionary Tribunal.

Picture to yourself for a moment the scene: the gallery, filled with hunger-maddened women, driven to every extremity of fury by wrongs long felt and, as they believed, only recently overthrown, the man standing in the dock who had been the King of France, and whom these people were taught to regard as the author of their misfortunes; a group of people on the Bench who were never judges, but accusers of the man who was to be tried; and the wild mob in the background in ragged national garb; all the turmoil and the turbulence of a French crowd that has lost its head, and in the centre Malesherbes, just as dignified and gracious as he had ever been, addressing Louis XVI by the old courtly titles that had always been used in the proud days of Versailles. At last his treatment of the case got on the nerves of the Tribunal, and the President said to him, “From whence, Sir, do you derive authority to call Louis Capet by the name that we have abolished?” The old man looked them in the face and said: “From whence? From my contempt for you, and for my life.”

The end was foreseen, and Malesherbes followed his master to the scaffold, but not before there had been reaped on the red sickle of the guillotine the heads of his daughter, his son-in-law and his grandchildren, before his eyes. That was penalty this man knew before hand he would have to pay, and that he was ready to pay out of allegiance to his old master. Surely, something of this comes down to us through the centuries, and we can feel the courtly charm of the day that is long since dead, and may never come back to make gracious again the earth, the courage, the knowledge, the learning... all given, freely given to the master who had rejected his counsels, and by rejecting them had lost his kingdom and his life.

A member of the Bar must, therefore, be prepared to accept a brief pro bono publico … for public good… that is without charging any professional fees. It will do damage to the image and the interests of the profession were we to be seen as “no fee, no work” lawyers even where the public interest or justice demands that a particular person should be assisted professionally.

Furthermore, no member of the profession should refuse a case for which they are properly briefed, for which they are available and which is within the area of their expertise or practice in the profession. We cannot refuse the instruction of clients simply because we don’t like them, their race, or ethnic groups, their politics, religion, sex or for fear of the authorities. We should remember Sir Hartley Shawcross’s famous warning as Attorney-General of the United Kingdom (popularly called “The Shawcross Doctrine”) when he heard that certain English barristers were reluctant to accept the brief for the defence of Jomo Kenyatta in Kenya on criminal charges of managing the Mau Mau brought against him by the British Colonial Government. To the eternal credit of the legal profession in Nigeria, Chief H O Davies and Chief Kola Balogun flew to Kenya and joined Denis Pritt QC in the defence. That is a noble and sacred tradition. It is profound misconduct not to observe it.

In 1792, prosecution was brought against Tom Paine because he published a book entitled The Rights of Man. The great advocate, Erskine, was sent the brief to defend. The then Prince of Wales to whom Erskine was a legal adviser viewed Erskine’s acceptance of the brief with disfavour and cancelled Erskine’s retainer. Erskine was unmoved and said in a statement that has become a credo for all lawyers: “From the moment that any advocate can be permitted to say that he will and will not stand between the Crown and the subject arraigned in the Court where he daily sits to practise, from that moment, the liberties of England are at an end.”

These things ought to be known and ought to be remembered. They ought to form part of the teaching, training and practice of every lawyer. Our studies are not merely a collection of rules out of black books and ancient, musty documents. The men who ennobled our profession, who have shown the heights to which it can be raised; they also form a part of our teaching, and the history of their lives should be studied and mastered by every lawyer. So taught what a study it is! There is nothing comparable to it in the world.

On “The Romance of the Law” our distinguished English jurist points out, “Suppose we look back to the pages of history and glance for a moment down the vast corridors of time, what is it that we see? Race succeeds race, and dynasty follows dynasty like shadow pictures of a moving film; conquerors, with their great armies fill for a moment the spot of light, and pass away, to be followed by line after line of captives in chains; by the spectres of famine and disease and the havoc and horror that have always and forever will follow the panoply and pomp of war. The painted glory of kings and emperors brightens for a moment the passing show, and they too pass away… out of the darkness into the light, and out of the light back to the darkness again”.

“Is there then nothing in all this mutability of things that can stand secure? Is there no single true ideal that makes life worth the living through? My answer is, “Yes,” there is the spirit of justice, and it lies with us (lawyers) to see that that shall be preserved and shall remain, though the civilizations as we know them today shall crumble into dust and the great cities of the earth return once more to the waste places from which they sprang.”

He concludes: “To the Romans justice was a goddess, and surely she may without treason to our faith remain a goddess still; the goddess whose symbols are known to all; a throne that tempests cannot shake; a pulse that passion cannot stir; eyes that are blind to all feelings of favour or ill-will, and the sword that falls on all offenders with equal certainty and with impartial strength.”

This, then, is she to whose service we are committed and dedicated and in the temple that holds her shrine all we, who study and practice the law and speak its language, can gather together as one congregation and worship side by side as we have been doing this week.

I must, therefore, commend us all to continue to bear in mind that ours is an awesome calling. Our profession requires us to be leaders. Shakespeare’s Hamlet saw himself as the scourge and minister of the Denmark of his time. We are not the scourge of anyone; we are rather the ministers for the law, for fair treatment, for truth and for justice anywhere, everywhere. We prosecute offenders, social evils and the enemies of society. We defend, protect and safeguard the lives, freedoms and property of all humankind – even of animal animals – from before birth until after death: from the womb to the tomb. We augur mis-government at a distance and snuff the approach to tyranny in every tainted breeze. We are the conscience of society. And as magistrates and judges we have the greatest and most solemn responsibility – next only to God – in deciding and sitting in judgment over the lives and affairs of our fellow human beings.

And in reminding us all of our enduring responsibility and leadership, I shall refer you to the words of the great Lord Denning, the Master who knows who said in the concluding paragraph of his book, What Next in the Law? “We have to respect all that Parliament has done, and may do, in the granting of powers… and of rights and immunities… but let us build a body of law to see that these powers are not misused or abused, combined with upright judges to enforce the law. It is a task which I commend to all. If we achieve it, we shall be able to say with Milton:

Oh how comely it is and how reviving,

To the spirits of just men long oppressed!

When God into the hands of their deliverer

Puts invincible might…

The might of the law itself.

We are also told that the law and practice that no man should be condemned before being heard, which finds fair hearing provisions in the constitutions of democratic states, is derived from Magna Carta 1215. I disagree. The concept or law or practice or principle of fair hearing is biblical. When God asked Adam why he ate the apple: God: omnipotent, omnipresent, and omniscient very well knew. He was giving Adam the opportunity to be heard. Fair hearing is not only a constitutional right or a human right; it is like most constitutional human rights, a God-given right.

Law is an indispensable mechanism of all governments whether democratic, dictatorial, or monarchical. All systems of government pay homage to some form of legal norms. Which other profession is almost always given a seat in the government of almost all nations? Let us imagine for a moment, a world without lawyers, and therefore without law. I am right, am I not, that if lawyers did not exist it will be necessary to invent them.

We must therefore by our collective and individual example as members of this noble profession continue to be the safety valve of democracy, human rights and the rule of law. All the calumny and vituperative tirades are unjust to us, grossly unjust indeed. It is our responsibility to deal with the people’s misfortunes, problems and difficulties within the complexities of society. In spite of technological developments, no society has been able to avoid these problems because they arise from the very nature of society itself and whether we like it or not such problems will continue to be with us and must be solved.

J W Davies, a past President of the American Bar who later became Ambassador to the Court of Saint James’s in London brilliantly defended our profession in his address to the American Bar Association when he said: “True, we build no bridges. We raise no tower. We construct no engines. We paint no pictures. There is little of all that we do which the eyes of men can see. But we smooth out difficulties; we relieve stress; we correct mistakes; we take up other men’s burdens; and by our efforts we make possible the peaceful life of man in a peaceful state.

The advocate has been, since the days of the Greek and Roman democracies, an essential and popular figure in all civilized society. “There he goes,” said the plebs, impressed and admiring, as Hortensius or Cicero swept into the forum; and crowds whispered and made way, and sometimes roared with vehement pleasure. No matter what anybody thinks, no matter what anybody says, ours remains the noblest and the greatest profession on earth.

This great honour carries with it very grave and great responsibilities. We must carry cross with crown: we must carry pain with palm; we must carry our gall with our glory. Ladies and gentlemen, let us never forget that being Lawyers, we have an enduring responsibility: We Are Called to Leadership.

I will now conclude with Lord Denning: In one of his many splendid books, Landmarks in the Law, Lord Denning, Master of the Rolls, quotes the celebrated speech of that distinguished 18th century English jurist and advocate, Henry Lord Brougham, who, more than one and a half centuries ago, had the honour of moving the House of Commons to pass and enact the great English Law Reform Act of 1828 when he said: “It was the boast of Augustus … that he found Rome of brick, and left it of marble; but how much nobler will it be the Sovereign’s boast when he shall have it to say that he found law dear, and left it cheap; found it a sealed book; left it a living letter; found it the patrimony of the rich... left it the inheritance of the poor; found it the two-edged sword of craft and oppression … left it the staff of honesty and the shield of innocence.”

It was with the spirit and vision of Lord Brougham that in moving Parliament to pass The Gambia Law Reform Commission Act in May 1983 that I said: “How noble will be the boast of this Government, and even much more of this Parliament, when this generation of Gambians, and even much more the generation of Gambians yet to come, shall have it to say that we found law dear, and left it cheap; found it a sealed book; left it a living letter; found it the patrimony of colonial craft and oppression, left it the inheritance of the poor and dynamic shield and spirit of the sovereign republican aspirations of The Gambian people.”

And today I say to you all, how noble will be the boast of us all, and even much more of all African Bar Associations, Law Faculties, Law Societies and Law Schools when this generation of Africans, and even much more the generation of Africans yet to come, will say that we found the law dear, and left it cheap; found it a sealed book, left it a living letter; found it the patrimony of colonial craft and oppression, left it not only the inheritance of the poor, not only the staff of honesty, not only the shield of innocence, not only the dynamic spirit of the sovereign aspirations of the African but also the renaissance of our peoples and their contribution to the great civilization of the universal.

Mr Chairman, as a young man, I saw visions; visions of a new Africa with a glorious tradition and historic past rising up again to the challenges of our times; visions of a mighty continent emerging again from the great schemes of the world with love of freedom in its sinews to suffer wrong no more and rewrite the history of our ancestors.

As a young man, I saw visions. I do not want to doubt that, as an old man, I will dream dreams. I trust that I will dream my dreams amidst the protection of the law and the security of justice for the weak, the meek and the poor. And I pray that we guard our laws and keep our faith that there is peace, progress and prosperity for all.