His remarks came during the testimony of the former BCC Chief Executive Officer Mustapha Batchilly on multiple allegations of financial mismanagement, improper contract awards, and unlawful allowances spanning the 2019 to 2022 implementation period.

The session began with the presentation of payment vouchers and council documents, including financial records and meeting drafts from 2020 to 2021. One of the key issues was the disbursement of 50 percent of a D3 million contract to the Mbolo Association, an NGO which Batchilly said had signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the council based on its activities. He admitted, however, that the proper procedures were not followed in issuing the payment.

Batchilly also faced questions regarding substantial allowances paid to members of the Ostend project’s steering committee. It was revealed that members, including Batchilly himself, received D7,500 as a monthly allowance solely for being part of the committee, alongside daily sitting allowances (D1,000).

When asked to justify the existence of multiple overlapping payments, Batchilly was unable to provide a credible explanation.

Batchilly’s testimony reveals that the adviser to the mayor and the deputy mayor also received allowances from the project, claiming Sanneh was asked by the mayor to represent her on the project.

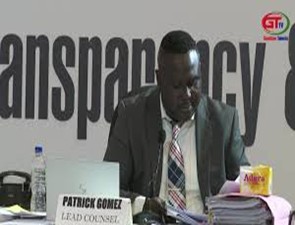

However, the lead counsel challenged the legality of such a role, pointing out that the deputy mayor is the official representative of the mayor in his absence. Batchilly insisted the mayor had asked Sanneh to take part.

When asked who formed the committee that oversaw the project, Batchilly stated that the first one was created with his involvement, while the second was formed by the mayor.

He admitted that the committee sat and decided on its own to increase their allowances. Lead Counsel Gomez responded sternly, stating that members were paying themselves without delivering on their responsibilities.

The inquiry also exposed the payment of festive bonuses to project staff. These included Christmas, Tobaski, and Koriteh bonuses, which were granted without any legal basis or official work requirement.

Batchilly admitted that these bonuses were disbursed and claimed the project coordinator supported the idea. However, Lead Counsel Gomez challenged him, stating that there was no provision for such payments. “You cannot give bonuses, you cannot give free money,” Gomez said, calling the payments unjustifiable and illegal.

The inquiry then shifted to the process of awarding contracts under the Ostend project. One of the most controversial cases involved a contract awarded to Jalakolong Construction Company for over D2.5 million to rehabilitate the Crab Island facility. The company was later declared bankrupt, and BCC was unable to recover the funds. Batchilly admitted that the contractor's financial background was not properly vetted.

Another payment of D600,000 was issued to Demba’s Trading for the supply of 60 dustbins. However, only 17 bins were delivered.

Batchilly admitted to approving the contract even though he knew it was unlawful, explaining that the deputy mayor initiated the procurement. He confirmed that no market survey was conducted and no delivery note was properly verified. When asked why he approved the payment under such conditions, Batchilly admitted that he was supposed to follow the correct procedures but failed to do so.

Auditors also flagged more than D1 million in expenses that were unrelated to the project, including community town hall meetings which were not captured in the technical proposal. Batchilly defended the meetings as a means to engage the public, but conceded that they were not part of the approved project activities.

Another significant controversy involved a fuel expenditure of D755,984, reportedly paid to the project team. Batchilly claimed that the project team did not receive any fuel and could not provide documentation to prove how the money was spent. He was asked to produce evidence of delivery.

A series of unauthorised payments were also scrutinized. D100,000 was paid to Mbenga Design for a bill of quantity, and D52,500 was paid to Director of Planning Katim Touray for project verification work duties that fall within his official role.

Batchilly admitted that these payments were unlawful and agreed that the money should be recovered.

An additional D895,335 was given to Touray through an imprest account for fencing the Mile 2 dumpsite. Batchilly said the cash was returned, but the chairperson Jainaba Bah stated that the act itself was still illegal, regardless of whether the funds were reimbursed, as it violated the Local Government Finance and Audit Act.

The inquiry also examined payments related to foreign consultants under the Ostend project. Joanas, a consultant from Belgium, was paid a monthly allowance of €5,600, equivalent to D344,777.