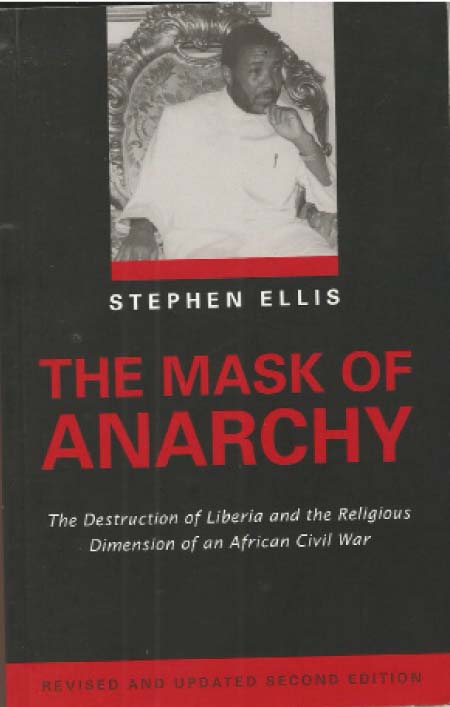

The

Mask of Anarchy, Stephen Ellis, Hurst and Company, 2007 (revised and updated

edition)

In

this ground breaking work Ellis not only traces the course of the Liberian

Civil War of 1989 to 1996 and 1999-2003, but also explores its possible causes

and terrible human cost of the war. It is cliché to say that Liberia was one of

the most violent African countries in the 1990s, when thousands of teenage

fighters laid siege to their own country, looted it, raped it and destroyed it

under the guidance of greedy and venal elders called warlords such as Charles

Taylor, Prince Johnson, Alhaji Kromah, George Boley, Rossevelt Johnson

(317-318) who led morphed and amorphous rebel killer squads such as

NPLF, ULIMO, LPC (xiv) etc.

Ellis

traces the history of the civil war that has seared Liberia, and critically

looks at the political, ethnic and cultural roots of the war. Politically, the

author blames the infamous Doe coup of April 1980. This was a bad coup. The

bloodiness-President Tolbert and his entire cabinet were tied to stakes and

shot (53). The world was shocked, and the anger generated by the brutality and

subsequent shocking events under Samuel Doe led to the explosion of 24 December

1989 when Charles Taylor, freshly sprung from jail in USA, fired the first shot

of the war. Ellis contends that even Taylor and Doe, who was subsequently

killed in terrible way, could not fathom the extend and duration of the war

they unleashed on the poor people of Liberia.

Another

interesting aspect of the book is Ellis’ attempt to analyze the cultural angle

of the war. He contends that cult, magic, spirit belief and religion played a

part in the execution of the war. The rebels used juju and paid particular

attention to the spiritual and arcane. The war lords employed juju men and

usually invoked religion to justify their boldly enterprises.

Ellis

also ably demonstrates the spill over effect of the war in Sierra Leone, Guinea

and later, Ivory Coast showing how nearly the Liberia war had become a sub

regional spark plug which could have engulfed the region into a big inferno.

The role of the ECOMOG peace keeping force in prolonging or stifling the war s

also discussed and Ellis believes that the debate on the real role of ECOMOG in

Liberia will continue to be debated.

In

his discussion of the casualties of the war, Ellis is inconclusive as he cites

various figures from 15 to 45,000 killed between 1989 to 1997 (312). Yet, he

contends that the human cost remains palpable in the huge mass graves and

refugee camps dotted in West Africa.

The

annex has a list of the dramatis personae of the war from Taylor to Doe, which

would-be useful reference for those who are interested in the names of the war

lords who have heaped so much pain and suffering to Liberia, once a prosperous

country proud of its legacy and civility. This is an interesting and

informative book. Highly recommended.

Available

at Timbooktoo.4494345