Introduction

Unlike the French who completely replaced the local chiefs with French officials, the British administered their colonies through preexisting authorities and structures.

Historians are generally agreed that Lord Lugard perfected the system of rule through the chiefs in Northern Nigeria, in the second decade of the 1900s. However, as explained below, The Gambia Protectorate created in 1893, was one of the earliest spaces for British experimentation with the policy of indigenizing of the colonial state, through the use of local customary institutions and values to meet their need for cheap, yet effective minimum administration in their colonies.

Background on the Sarahuli

The Sarahuli have produced numerous traditional chiefs during the colonial period one of whom Yugo Kasse Drammeh is profiled below. But before doing that allow me to put the Sarahuli into brief historical context: also called Soninke, the Sarahuli are also found in Mali, Mauretania and Mali. They constituted the old Kingdom of Gajaga, which thrived in the 19th century ‘on either side of the River Senegal and River Falame’, according to Professor Abdoulaye Bathily, a leading scholar on the history of the Soninke. Other historians like Phillip Curtin also use the name Galam, for Gajaga.

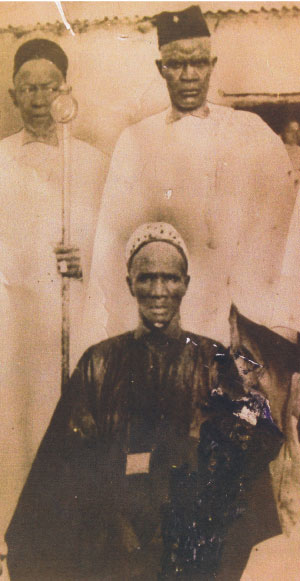

Yugo Kasse Drammeh

Yugo was appointed chief of Sandu District, the Gambia, in April 1942. Described by the Travelling Commissioners variously as ‘energetic’ ‘promising’ and ‘liable to be too autocratic’; a mixed bag of epithets which shows the ambivalence with which his colonial bosses held him. He is credited with been the first chief to appoint a Native Authority, an advisory council. Thus unlike other chiefs, he shared power through regular consultations. He was always anxious to improve his district, the smallest in the Upper River Region covering a mere 127 square miles. He sunk wells to water livestock and provide water to people, built markets, seed stores and a decent rest house at Diabugu. His district was always trouble free, as he preferred to settle disputes through the District Authority, which is why his collection of court fees was very poor.

Conclusion

Chiefs like him were the cornerstone of colonial administration in the Gambia. They collected taxes, dispensed ‘native’ justice and were expected to be guardians of local culture and traditions also. For this they were always well rewarded by the colonial administration in the form of stipends, commissions and also medallions and badges of honour during the Annual Chiefs meetings from 1944. But against errant chiefs, the colonialists could be ruthless: they were punished with jail, dismissal or the highly shameful banishment.